Installation view of the El Paso Community College Art Faculty Exhibition, on view at the El Paso International Museum of Art through April 30

In the former home of the Turney family on a historic block in El Paso — a historic block with ax throwing and work share spaces cropping up — lies the International Museum of Art. Formerly the El Paso Museum of Art from 1947 to 1998, the original residence was built in 1908 for W. W. Turney, a rancher, lawyer, and state legislator. This is a memorably strange museum built with private and now public collections that are housed in various rooms and hallways, rather than regular curation. (Also, the museum so happens to be seeking a new director.) Here, the El Paso Community College (EPCC) Art Faculty Exhibition is currently on view, amidst a labyrinth of marble stairs, stained glass, and Corinthian columns.

The EPCC exhibition boasts a variety of mediums and touches on a range of personal and political themes. Zoe Spiliotis’s hyper-bright symmetrical paintings adorn several walls in the gallery. Arresting in their opticals, these works hold moons, cranes, and water, as if depicting lost places of lore. Spiliotis gets at painting essentialism, in the manner of Mark Rothko or Hilma af Klint. Many of the same day-glow colors appear in Isadora Stowe’s installation of prints and paintings on geometric canvases and laser-cut wood icons of the borderlands: lone houses, what seem to be military planes, cacti, yarrow-like wildflowers, moths, candies, and long-cast shadows. Many of the faculty members are from Mexico and the U.S./Mexico border, and the visual language of the area permeates the exhibition. Motifs like the border wall, a hairless dog, and a quetzal-feather crown in Marco Sanchez’s etchings.

Some of the most personal works included are the body-wear pieces by Davina Miraval. Several installations flank the floating gallery walls in the center of the exhibition space, the works draped at neck-level. Her Marriage Series works, titled Struggle, Hidden, Burden, and Lazo, appear delicate and cold. The putrid purple hue of one neck piece, Copulace is at once attractive and repellent, like a ring of offal studded with petite yellow flowers hung against the high-gloss black gallery wall.

Installation view of the El Paso Community College Art Faculty Exhibition, on view at the El Paso International Museum of Art through April 30

The entire room dins with an archaic video game bleep sound, which emanates from Cleo Arevalo’s performative and drawing-based video work. In the video, a projector blazes light over Arevalo and a tacked-up canvas, playing scenes of people surging over a Moroccan border wall. Over the projected video, Arevalo traces the movements and forms of the cascade. The resulting drawing is hung next to the monitor where the video is playing. The rust-tone drawing has the effect of a cave painting or polygraph test, while the video’s desperation and tension is heightened by the droll beeping of the audio.

Another impactful series of work in the exhibition is dependent on sound: Brack Morrow’s EAR1 Wind Bow, and Remote Station Violin. Both are compiled of instruments and electronics, and almost look like weapons — guns mounted on table-top stands. The video behind the sculptural sound works demonstrates how they work “in the field,” with raindrops or wind causing a cacophony of reverberating sound. At times the level of the piece was so intense I had to remove the accompanying headphones and hold them an inch away from my ears. Something about the potency of what the instruments picked up in the ether served as a microcosmic reminder that the most powerful forces lie in the inconceivably miniature. Splitting atoms, melting quarks, and the like.

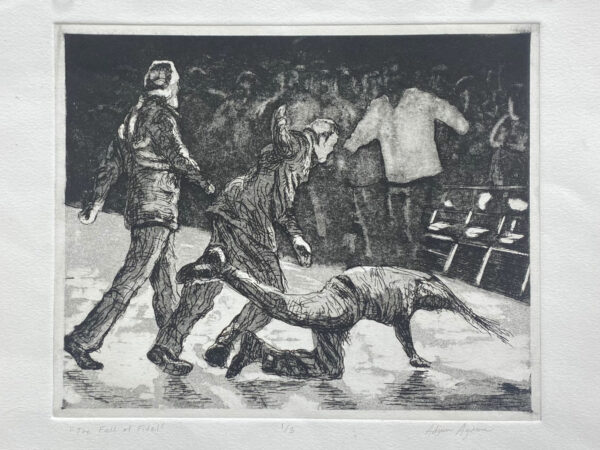

Power itself manifests as the unifying theme of the show. A small, solemn image by Adrian Aguirre on one of the back walls continues to hold my focus; an intaglio print of the famous moment when Cuban leader Fidel Castro tripped after delivering an address to graduating art instructors. The London Observer stated, after Castro’s death, that he was a “towering figure…who transformed a small Caribbean island into a major force in world affairs.” During his reign, Castro let the Soviet Union place nuclear weapons in Cuba, a defining moment in the Cold War. Though the Cuban Missile Crisis occurred 60 years ago, the tensions of nuclear war and authoritarian regimes are still very much globally at play. Contrasting these historic and current ideas with the image of Castro prone, below a white shirt in the background hovering like a flag of surrender, is thought-provoking, at the very least. It may be heartening or harrowing that while powerful men may fall, the methods they champion will endure.

The EPCC Art Faculty Exhibition is on view at the El Paso International Museum of Art until April 30th, 2022. There is a closing reception April 28th, from 3:00-5:00 PM.