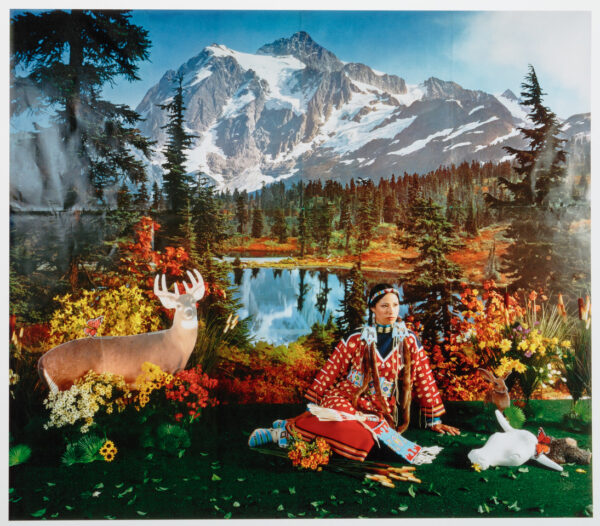

Wendy Red Star, “Indian Summer—Four Seasons,” 2006, archival pigment print on sunset fiber rag, 23 x 26 inches. Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D., 2016 2016.46.1.1, Collection of The Newark Museum of Art © Wendy Red Star.

Wendy Red Star: A Scratch on the Earth, on view at the San Antonio Museum of Art, is an illuminating mid-career survey that speaks to the artist’s Native American heritage and a seldom-seen America. Originally organized by the Newark Museum of Art, the exhibition features roughly 40 works of photography, textiles, and mixed-media installations, all made between 2006 and 2019. The survey is as diaristic as it is didactic, a reworking of ancestral and archival information into something very contemporary, and very personal.

Red Star, who is of Apsáalooke (Crow) and Irish descent, grew up on her tribe’s reservation in south-central Montana. Identity and otherness — a straddling of worlds — seems to be the driving force in her work, which can best be described as informative, ironic, and oftentimes funny.

Conceptual execution and cultural cliché kick it off at the show’s entrance with the photographic series Four Seasons (2006). Red Star has posed in a traditional elk-tooth dress against four decidedly fake nature scenes — Fall, Winter, Spring, and the aptly titled Indian Summer — each a kitschy cross between Sears Portrait Studio and a science diorama. The artist looks on with an air of solemnity in each photo, as faux flora and fauna (an inflatable elk, Astroturf, a creased backdrop that could fold up like a pamphlet) complete the ethnographic look.

This dilemma of authenticity and artificiality sharply plays into the trope of Indigenous spirituality, one of many romanticized stereotypes that Red Star critiques in her work. Red Star seems all too aware of the Native American as a relic rather than a reality, symbolically preserved from the past much like a taxidermy museum display. Yet her own subversive role in that narrative, as a contemporary Crow artist bridging the past and present through her research and art, is equally central to the exhibition.

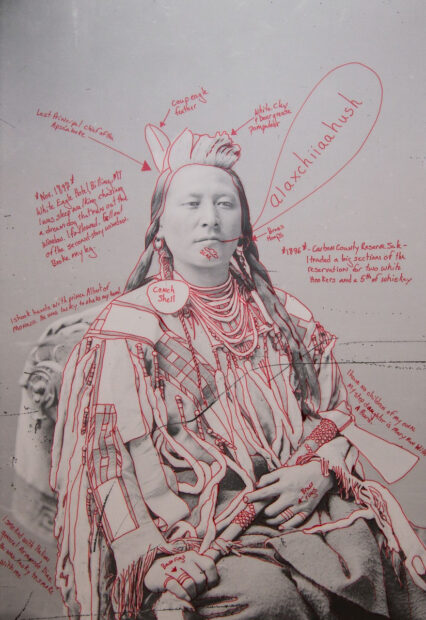

Wendy Red Star, “Alaxchiiaahush/ Many War Achievements/ Plenty Coups” from the series “1880 Crow Peace Delegation,” 2014. Pigment print on archival photo-paper, 17 x 25 inches (each). Gift of Wendy Red Star in memory of Loren G. Lipson, M.D., and Purchase 2018 Sophronia Anderson Bequest Fund and John J. O’Neill Bequest Fund 2018.26.1.4A,B, Collection of The Newark Museum of Art © Wendy Red Star.

In the photo series 1880 Crow Peace Delegation (2014), Red Star has traced over 10 black-and-white images of prominent Crow leaders in red Sharpie, reminiscent of the transparencies once used for overhead projectors in school. Those clear acetate sheets, enthusiastically annotated in marker by some teacher, were often layered on top of the original information to modify its content. Red Star’s painstaking tracings of each portrait — the images were taken during the Crow delegation’s visit to Washington D.C. that same year — afford us, the students, a new way of viewing the sitters’ history.

Two photos, Alaxchiiaahush/Many War Achievements/Plenty Coups, are of the last principal chief of the Apsáalooke; Red Star’s writings occupy the empty space around Plenty Coups, adding flavor to his stoic yet generic portrait, including factoid-y details about his dress and accouterments, and direct quotes from him: “‘The ground on which we stand is sacred ground. It is the blood of our ancestors.’” They also include her own spin: “I shook hands with Prince Albert of Monaco. He was lucky to shake my hand.”

In the years following the 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, the federal government enacted land policies that were aimed at breaking up Native American societies and tribal territories. Chief Plenty Coups believed the Crow tribe would be spared from these policies, given their allyship with the Americans during the Indian Wars. This was not so: A Scratch on the Earth refers to the subsequent borders that were drawn.

Wendy Red Star, “Family Portrait – Walla, Marlon, Doonie,” 2011, cotton broadcloth with archival ink, 44 x 44 inches. Autry Museum of the American West, Los Angeles, Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. 2018.14.2. © Wendy Red Star.

Map of the Allotted Lands of the Crow Reservation, Montana—A Tribute to Many Good Women (2019) features a wall-sized map of the reservation from 1907, overlayed with pictures of present-day Crow women who still have lineal ties to that land. (The Apsáalooke kinship system is matrilineal, matrilocal, and matriarchal.)

Throughout the exhibition, Red Star points to the not-too-distant past when depicting present-day Crow culture, and by extension, Native American culture. In Let Them Have Their Voice (2016), 15 Crow chiefs have been carefully excised from their historical portraits, leaving only the outlines of each image. This historical dissonance between eradication and preservation is key, with empty portraits — taken from the 1908 book, The North American Indian, by Edward S. Curtis — supplying a full picture.

The author, a prolific American photographer and ethnologist who took more than 40,000 images of early twentieth century Native American life, has been criticized in recent times for those images. His romanticized portrayal of Native Americans — as a vanishing people, as a symbol of the “noble savage” — arguably ignored the grim realities for many in these communities who were struggling to assimilate into Western culture and living in poverty on reservations.

At the time of the book’s publication, Curtis also recorded traditional Crow songs, which accompany the installation. Voices fill the gallery with a haunting, almost mournful sound, giving me a knee-jerk wonder if that’s precisely the point. Just as Red Star takes great care in researching her tribal ancestry, so too is her prowess for meta fakery (thanks to depictions reinforced by documentarians like Edward S. Curtis). The role of the museum and the role of the museum visitor who is consuming this Native narrative, largely manufactured by the non-Native, is part of the dissonance, and therefore part of the critique.

The multimedia installation Sweat Lodge (2019) furthers this blurring of ethnography, irony, and art: a “geodesic dome,” containing an immersive video by Red Star and collaborator Amelia Winger-Bearskin, reveals the mysterious sweep of the Montana landscape. While crouched inside, contemplating the natural world via 360 degrees of screens, the viewer is transported to another way of life. (The viewer is also sitting on drab office carpet.)

According to the piece’s wall text, sweat lodges remain an important aspect to Crow life, and Red Star’s installation — covered in store-bought bedspreads rather than animal pelts — reveals a more modern and practical approach to the tradition. Outside the structure, plastic plants and an artificial campfire invite more of that tongue-in-cheek critique: a bit of teaching, and a bit of teasing. “I come from a humorous background, not just my Crow side, but my Irish side as well,” Red Star remarked in a 2016 interview. “I’ve always seen things through this ironic lens. I’m always laughing.”

Wendy Red Star, “My Home is Where My Tipi Sits (Sweat Lodges),” 2011, archival pigment print on sunset fiber rag, 57 x 72 inches. Collection of the artist © Wendy Red Star.

In Red Star’s photojournalistic My Home is Where My Tipi Sits (Sweat Lodges) (2011), we see these structures in practicum; set up in somebody’s yard, covered in old blankets, a water container nearby, presumably to pour on the lodge’s hot stones. (This particular series showcases other everyday images as well, including churches, HUD houses, and “rez cars.”)

The survey’s highlight, Where They Make the Noise (1904-2016) is a fascinating visual and textual — and moving and personal — timeline of Crow Fair, a festival that attracts tens of thousands of visitors to Montana each year, and which Red Star and her family have taken part in for generations. The installation wraps chronologically around the gallery’s perimeter on a single thread of graphite. Its compact narrative of cutout photos and handwritten notes (written right on the museum wall) assemble a parade route over one hundred years in the making.

From photos of traditionally decked-out elders on horseback, to Dodge Ram trucks covered in Indigenous blankets, to pictures of Red Star as a child as well as those of her own doppelgänger daughter, the images on the timeline articulate an America not enough Americans have seen.

This is why A Scratch on the Earth is essential reading for anyone who wants to better understand the American experience by way of its Native American foundation. Red Star’s artwork is an autobiographical revelation, both personally and culturally, offering up lesser-known parts of our history through a living, breathing heritage. The ground on which we stand, scratches and all.

A Scratch on the Earth runs through May 8, 2022 at San Antonio Museum of Art.