Ed Note: In fall 2021, Michelle Kraft taught art history for a semester in Spain to a group of university students from Texas. In this series of three articles, “Dispatches from Spain,” she reflects upon her time there. Read Part One here, and Part Two here.

En la noche esplendorosa de Plenilunio, bajo un arco de la muralla, un hombre cantaba: ¡Ave María Purísima! Me dijeron era un “sereno” y decidí quedarme en Ávila . . .

In 1917, a great snowfall stalled an express train from Madrid to Paris, stranding it at Ávila, Spain. Among its passengers was the Italian painter Guido Caprotti; he had been lured to Spain by a commission to copy Diego Velazquez’s Pablillos de Valladolid, in the Prado Museum. Stuck and wandering the narrow avenues of the medieval walled city over the course of three days, Caprotti was enchanted. He decided to stay.

Steeped in his home country’s tradition of landscape painting, the artist applied this same expertise to a study of Ávila’s old city center — its Romanesque churches, plazas, by-ways, and the warm-colored ancient stones of its murallas. The mysticism of the town — this “land of saints and songs” — intrigued Caprotti. It wasn’t long before he turned his attention to painting its denizens, too: Ávila’s friars and its nuns and its faithful. These he portrayed with sympathy and acuity, imparting in their likenesses the measured doses of tranquility, gravity, and exuberance that he found within the abulenses themselves. The Coleccíon Caprotti is now housed in Ávila’s Renaissance-era Palacio de Superunda, the artist’s former home and studio — a residency that was temporarily interrupted by the Spanish Civil War, after which the artist returned once more to Ávila.

In visiting the Coleccíon Caprotti, I was struck by how the Italian painter’s professional trajectory mirrored that of the Taos Society of Artists in New Mexico. In 1898, only a generation prior to Caprotti’s unplanned sojourn in Ávila, two American painters — Bert Phillips and Ernest Blumenschein — found themselves stranded outside Taos when their wagon wheel broke apart on the rough canyon road. Phillips waited for three days with the wagon and gear while Blumenschein took the wheel to Taos for repairs. While their original plan had been to continue south to Mexico, the two instead found themselves captivated by the Northern New Mexico landscape, its light, and its inhabitants. Phillips decided to stay, though it would take Blumenschein over ten years to make his own permanent move. By 1915, though, the pair had attracted other artists to Taos, forming the famous art colony, which concerned itself with painting the area’s unique peoples and landscapes.

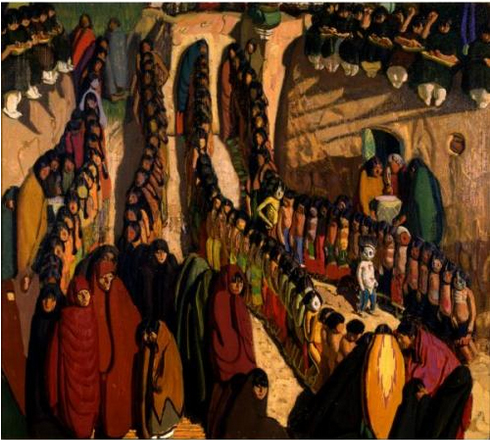

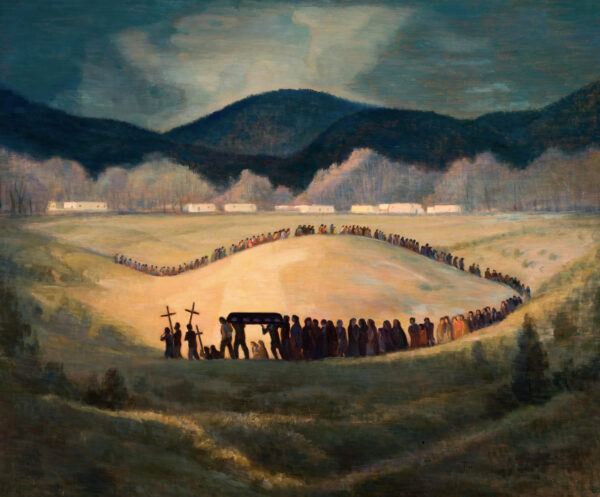

Though separated by the Atlantic and most of a continent, the Old World of Ávila and the “New” of Taos are firmly knitted together by the thread of Spain’s Catholic church. Their shared spirituality is found in the austere fervor of Guido Caprotti’s Procesión en la ermita de Valmaseda (1935), just as it is in Burt Harwood’s Church Procession, Chimayo (1916), or Ernest Blumenschein’s Dance at Taos (1923). In Caprotti’s Procesión — as with the Harwood and Blumenschein works — it is the communal that is emphasized over the individual, the mutuality of a devotion that is not just vertical (heavenward) in its expression, but is horizontal, as well. The interpretive material at the Coleccíon Caprotti translates, “More than reproducing what he saw, the painter dedicated his time to finding the secret of the city, to define states of the spirit in an urban landscape weighted with sobriety, even roughness, that distills the essence of Spanish mystic tradition and serenity of soul, the simultaneous tragedy and sweetness of Castile.”

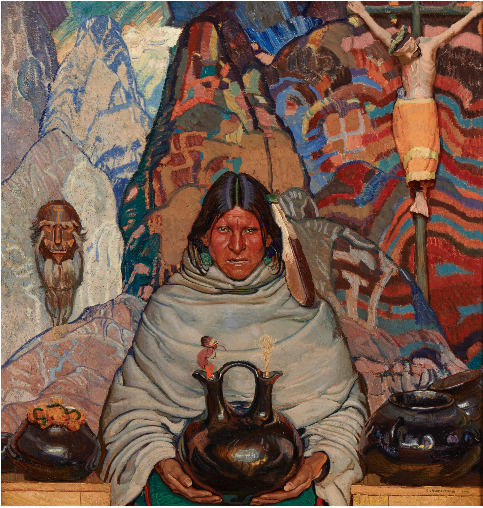

In this way, Caprotti’s sensibilities towards his subjects were perhaps less idealized than those of Taos painters such as E. Irving Couse or Joseph Henry Sharp. Rather, the Italian artist identified with Spain’s Generation of ’98, the poets and essayists who were deeply affected by the social, moral, and political disruption left in the wake of the Spanish-American War. Caprotti’s Spanish influences, therefore, may be found in the work of such painters as Ignacio Zuloaga and others who, as the museum’s textual materials put it, concerned themselves with a “rustic and tragic Spain.” Preoccupied with the country’s revitalization, these artists’ inspirations were modernist in theory but naturalistic in execution; their visual vernacular situated its romance — if it had any at all — within Spain’s dusty and derelict villages. Generation of ‘98 artists and writers were nationalistic, albeit leftist; they were discontented and cynical. One can discern this tone of dubious irony within the facial expressions and pointed symmetry of Caprotti’s Misa. Ofrenda con Cristo (1941); similar visual devices and attitude — though rooted in different soil — are likewise evident within Ernest Blumenschein’s Superstition (1921).

But any allusions to a stiff and formal liturgy, devoid of real significance, are belied by such works as Caprotti’s poignant A los Pies de Cristo (1953). Taken as a companion to Taos painter Walter Ufer’s Hunger (1919), we read in both works a faith that is elemental in its fervor, just as essential to and sustaining of one’s being as water, food, and breath. Both scenes are rough and simple; each artist conveys in his subjects a yearning so keen in its self-recognition that the only reasonable response is abject humility. The two paintings are so very similar in composition, theme, and painterly qualities that it seems almost unthinkable that Caprotti and Ufer would have developed their works in isolation from one another, half a globe away.

But just as the gentle satire of Caprotti’s Misa. Ofrenda con Cristo seems the exception rather than the norm, so too does the candor of Ufer’s Hunger among the Taos painters. In their portrayals of the Taoseños around them, the Taos Society of Artists act mostly as detached outside observers, chronicling the habits and rituals of those native to the painters’ adopted home, as an archeologist might gather and preserve artifacts. Rarely do their subjects’ gazes meet our own, which leaves us as viewers free to scrutinize in peace and without the return of pointed eye contact, as with Caprotti’s Dos mujeres a misa. El ama del cura (1917).

In this work, we are left to wonder who, or what, is the priest’s “love,” or mistress? Is “mistress” metaphorical, as in the mass itself, or an allusion to the two female devotees and others like them? Is the term to be taken literally, referring to the older woman whose challenging but benign stare meets our own? And if it is the latter, who then is the father of the girl whose arm the older woman clings to protectively? No matter how the title is to be interpreted, what Caprotti most points to is a practice of faith that is so intrinsic to the abulenses that it endures amidst human foibles. It is entrenched within the super-ego of this place’s culture and history; even when paradoxical, it is frankly unapologetic. In works like this and others, Caprotti imbues in his abulenses a dignity, a self-deprecating humor, and a stoicism that sets them on equal footing with the viewer. It is this humanity and authenticity that pervade Caprotti’s paintings of the residents of his adopted hometown, and perhaps characterizes his work as different than the Taos artists: rather than a mere observer, Caprotti becomes a participant-observer in the life of the city of Ávila, an outsider-insider. These qualities are discernible, too, in comparing Bert Geer Phillips’ Burial Procession—Penitente Ceremonial—Near Taos (1925) to Caprotti’s similarly themed painting Procesión con Cristo (boceto), from 1920.

While in Phillips’ painting, our point of view is separated from the penetitente funeral procession — we watch from a safe distance atop a hill, looking downward upon the scene — in Caprotti’s, we are participating in the parade. Hugged on either side by the canyon-like walls of the calle, we are drawn in. We imagine ourselves one of the darkly hooded penitentes, we hear the shuffling of their/our feet, and we see the rhythmic lurch of the crucified Christ as a metronome in time with his bearers’ marching steps. Rather than an elevated view, as in Phillips’ piece, we are in the street with Caprotti’s penitent. Like him — like them — we participate in this rite of contrition, and we are connected to the spiritual mystery of the place and people of Ávila. Such artistic portrayal demands a certain measure of humility on the part of Guido Caprotti; and, as the city’s own daughter, Saint Teresa of Ávila, once pointed out, “While on earth, nothing is more needful than humility.”