Luis Jiménez, “Man on Fire,” 1969, fiberglass with acrylic urethane resin on painted wood fiberboard base, 106 1⁄4 x 80 1⁄4 x 29 1⁄2 inches, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Luis Jiménez (1940, El Paso, Texas – Hondo, New Mexico, 2006) was a socially concerned sculptor and printmaker. His monumental polychromed fiberglass sculptures, which he began making around 1963, were his most singular creations. Their evocation of custom hot rods and other products of popular culture provoked critical ire in the mainstream media. Jiménez pointed out that his molds are “identical to the molds that are made for canoes, auto bodies, hot tubs, etc.” (Jiménez 1994: 48). He was attracted to fiberglass because he regarded it as “a blue-collar process.” (See the Smithsonian Art Museum’s Meet the Artist: Luis Jiménez.) Jiménez told Michael Brenson that he sought to “stay as close as possible to the industrial process” and that he valued “the illusion of flawless finish,” (Brenson 1997: 15 – 16). As Charles D. Mitchell wrote, (1999: 101) such finishes were “largely abhorred as an element in the fine arts.” Jiménez enjoyed pointing out that his careful processes, capped by many coats of jet aircraft acrylic urethane and three clear coats, deliberately intensified “the plastic look” and resulted in “the finish that the critics love to hate” (Jiménez 1994: 48).

Luis Jiménez Senior’s Electric & Neon sign shop, “Horse Head” for The Bronco Drive-In, now the Bronco Swapmeet and Dance Hall, c. 1956-1957, El Paso, Texas. Photo: Roadside Architecture.com

According to Roadside Architecture.com, the Bronco opened in 1949 and closed in 1975. For another view of the horse and a picture of the marquee with the intact neon, go here.

Even a sympathetic writer such as Roberta Smith (now the co-chief critic at the New York Times) declared that Jiménez’s sculptures “look as if they belong in a very fancy gas station” (Smith 1976, 48). Jiménez was a populist sculptor who would not regard this as a bad thing. His artistic sensibilities were rooted in his experiences in Electric & Neon, his father Luis Jiménez Sr.’s sign shop in downtown El Paso. In addition to simple signs, the shop created large-scale “extravaganzas,” some of which combined neon and sculptural elements.

Jiménez says his father’s work was known to leading sign fabricators in New York, and that he made major signs for Las Vegas, including one for the Green Frog Lounge that featured a frog jumping up and down while it croaked. Closer to home, Jiménez Sr. made a ten-foot-high metal and neon rooster sign for a drive-in that crowed on the hour — until it was silenced by a neighborhood petition (Jiménez, 1984; 1985). Jimenez (1984) recalled helping with the twenty-foot-high horse head (with illuminated eyes). He added: “basically I’m still doing the same thing that I was doing then, and the kind of things he did in those spectaculars.”

In his interview with Peter Bermingham for the Archives of American Art (AAA), Jiménez recalls working on a three-dimensional concrete polar bear for a dry cleaning business when he was just six years old (Jiménez 1985). It was part of an extravaganza for Crystal Cleaners. This polar bear is far more accomplished than another horse’s head by the artist. In the AAA interview, Jiménez notes that when Frank Lloyd Wright visited El Paso, he criticized the local architecture but had high praise for the commercial signs that had been made in the family sign shop. I asked artist Gaspar Enriquez how these works were generally regarded in El Paso. “Most people in El Paso thought of them merely as signs,” he replied, “until after Luis came back from New York and began getting recognition—then they came to be regarded as something more important.”

Jiménez, who made no distinctions between commercial, or “low” art, and so-called “high” art, linked Chicano aesthetics to what Lucy Lippard calls “a broader popular culture” (Lippard 1994: 21). He had engaged directly with this popular culture by spray-painting hot rods in his father’s shop after normal business hours (Ennis, 1998). He also worked with fiberglass automobile bodies.

As a young man, Jiménez believed that all Mexicans and Chicanos had “inherent” artistic talents and interests (Jiménez, 1984; Lippard, 1994: 22). Jiménez had a deep connection to art in Mexico, dating back to a summer when he was six years old, during which he encountered Mexican murals, museums, and even a Henry Moore exhibition (an early influence on the artist), which provided a perspective unavailable in El Paso (or anywhere in the U.S.). He was a regular visitor to Mexico, and he studied at the Universidad Universitaria in Mexico City in 1964. “I never lost contact with the culture of Mexico,” Jiménez told Ennis (1998).

At the same time, Jiménez has always identified as a Chicano:

I grew up as a Chicano before it was a militant term. I’m comfortable with it. You needed a word because “Mexican” implied that you still had Mexican nationality. Mexicans don’t really accept Chicanos, they see us as traitors, and Anglo-Americans don’t quite accept Chicanos either. I come out of a minority within a minority, Mexican Protestants…. (Jiménez, 1984).

Jiménez adds that his situation in El Paso gave him the ability “to stand outside of both cultures,” which he considers to be advantageous “because that’s the role that the artist has always been in” (Jiménez, 1984).

He always had much to say about museums and exclusion:

I want my art to be public, part of everyday life. I think most museums are essentially mausoleums, and that art seen there has been removed from any social context or interaction. Certainly only a small percentage of Chicanos go. They’re not made welcome (Jiménez, 1984).

Having worked for a business that made commercial signs whose specific aim was to capture the attention of the public, Jiménez was determined to become a public artist whose work reflected his personal and cultural experiences. Because he disliked the “very limited audience” that is typical of museums and galleries, Jiménez sought to “expand that audience . . . [and become] an integral part of society” through public art (Jiménez: 1994: 94). Moreover, Jiménez wanted his art to “generate a meaningful dialogue” within a diverse community (Flores-Turney 1997: 11). In New York, he had observed that Blacks were cognizant of “their sense of obligation to a larger community,” and he felt the same responsibility (Jiménez, 1984). These ambitions are manifested in notes and sketches the artist made in New York from the late 1960s. Jiménez spent the rest of his life realizing them.

I argue that Man on Fire is Jiménez’s supreme creation. While it is the product of extraordinarily diverse interests and influences (including the Olmec were-jaguar myth, the human/mechanical hybrid theme, Aztec and European sculpture, Mexican history, the murals of Orozco, U.S. automobile emblems, and anti-Vietnam War protests), it is also, paradoxically, his most personal sculpture.

American Dream and Human/Mechanical Hybrids

Titian, “The Rape of Europa,” c. 1560-1562, oil on canvas, 70 x 81 inches, The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The man/mechanical synthesis — one of Jiménez’s favorite themes — leads directly to Man on Fire. Jiménez’s most famous work in this mode is a sculpture called American Dream, which is comprised of a woman who mates with a car. Jiménez views American Dream as a contemporary — if semi-mechanical — version of the classical themes of Leda and the Swan and Europa and the Bull, as do critics and scholars (Amaya, 1969; Quirarte 1973:117; Lippard 1994: 25).

Luis Jiménez, “The American Dream,” 1968-69, fiberglass with acrylic urethane resin, 20 x 31 x 35 1/2″ inches, The Anderson Museum of Contemporary Art, Roswell, New Mexico. Photo: Artnet

Shifra M. Goldman (1994: 10) calls American Dream “the ultimate symbiosis for a car-and-blond-worshiping U.S. male public.” These coupling icons of U.S. popular culture, however, mate as a consequence of mutual attraction, rather than the Greco-Roman mythological scenes featuring Zeus/Jupiter, which are rape scenarios. Jiménez (2007: 56) mentions the Olmec myth, as well as Europa and Pasiphae, and specifies: “the car is the god.”

Jiménez tried to get gallery representation in New York City by showing his slides to dealers, with no luck (sometimes they wouldn’t even look at them). He also felt that slides could not adequately convey the qualities of his sculptures.

Jiménez devised the guerrilla strategy of occupying a gallery with three sculptures: The American Dream, TV Image, and Sunbather. He chose the eminent Leo Castelli Gallery. Even though he knew the gallery would not add him to its stable of artists, Jiménez wanted to catch the attention of Ivan Karp, the savvy co-director. “You are a virtuoso,” Karp declared, after he had seen Jiménez’s drawings. Karp liked the sculptures, too. After some brainstorming, he told Jiménez to approach the Graham Gallery. Jiménez had already been to Graham, but Karp pointed out that they had just gotten a new director. The gallery took two pieces on a trial basis. Karp cleverly visited the gallery and raved about Jiménez’s work to David Herbert, the gallery’s new director, declaring: “Oh my God, you’ve got Jiménez’s! I mean, do you know those are the hottest underground pieces right now?” (Jimenez, 1985).

When artist Alfonso Ossorio visited Jiménez’s loft in Little Italy, he asked Herbert how many sales were needed to get the sculptor a one-person show. Ossorio purchased four Jiménez drawings on the spot to secure the one-person exhibition at Graham Gallery in 1969 (Jiménez, 1985).

The first sketch for the American Dream series of work was a particularly spontaneous creation. Jiménez rose one morning and found a piece of shirt-packaging cardboard on the table. He recalls grabbing a pen and “feverishly scribbling all these positions” of a woman coupling with a Volkswagon as studies for a sculpture on the “man/machine theme.” The artist notes that the woman’s breasts have the same shape as the car’s hubcaps (Jiménez 1994: 67).

These studies transfigure the obsessive auto-eroticism of adolescent America into a compact, cardboard Kama Sutra of car sex. The vehicle itself is transformed into something more than a site and symbol of adolescent eroticism: it becomes not merely a phallic surrogate, but a mobile and autonomous human surrogate as well.

These orgiastic undulations and multiple machinations eventually become fixated into the three-dimensional woman/vehicle intersection that David Hickey dubbed the “transmissionary position” (Hickey 1997b: 26). The first American Dream sculpture was made in 1967, though most are dated 1969, the year of Jiménez’s first one-person show at the Graham Gallery.

Jiménez deliberately made the personification of the American Dream blond. As he stated around 1970:

The Mexican American or anyone who is not blond or blue-eyed is super aware of it, because he does not fit this image. You see this happening in Harlem. . . . You see black people at some of the teenage dances wearing blonde hair and blue mascara above their eyes. They are desperately trying to fit the American image. And the same is true of the Mexicans. I had a roommate who walked on the shady side of the street because he didn’t want to be darker (Quirarte 1973: 120). Jiménez also notes that he saw prostitutes in Mexico wearing blond wigs.

In a lithograph (1970) and a drawing (1971) that he also titled American Dream, Jiménez transformed the bug-like auto into something sportier, like a Porsche. The white ground of the paper served as the road, which stretched into the distant background. The title was emblazoned with pop lettering based on the stars and stripes of the U.S. flag.

Like many contemporary U.S. artists, Jiménez was inspired by popular culture, though he utilized this imagery as an explicit critique of consumer society. In this respect, he felt a kinship with the work of Edward Keinholz (Jiménez, 1984). John Yau contrasts Warhol and Jiménez: “the former used either bland or celebrity images the viewer recognizes immediately, while the latter reinterprets charged symbols whose range of meanings both challenge and undermine the way we understand the world we live in” (Yau, 1994: 42).

In another variation called Cat Car (1968), the vehicle is synthesized into a jaguar/car/phallus/rocket hybrid poised to become airborne. The cat’s forelegs are disproportionately small, while the cabin is suggested in the rear portion of the vehicle. It rests on an oversized pair of wheels. Nonetheless, it appears to be blasting off. The pinkish remnants of the woman can here be interpreted as exhaust that accompanies the phallic cat vehicle’s lift-off. Cat Car dramatizes the totemic associations made between sports cars and wild cats. More broadly, sporty cars and rugged terrain vehicles often invoke totemic associations with sleek, fast, wild, and sometimes predatory creatures through their names, including Stingray, Barracuda, Viper, Firebird, Thunderbird, Mustang, Bronco, Ram, Cheetah, Cougar, Bobcat, Wildcat, and Jaguar.

Cat Car also points to an ancient Mesoamerican source for this entire series. Many Olmec jade figures combine aspects of jaguars and humans (for illustrations, see Coe 1996). They were dubbed “were-jaguar” figures. The U.S. scholar James Stirling speculated — probably erroneously — that the Olmecs believed that jaguars mated with women. Contemporary scholars reject Stirling’s identification of human/jaguar copulation scenes. See Miller and Taube (1993: 158) for an overview of the Stirling Hypothesis, which was advanced on the basis of two sculptures (Stirling 1955).

When Jiménez made American Dream, Coe (1965) was the most accessible source on the were-jaguar myth; it is cited by Jacinto Quirarte (1973: 117). Whitney Davis (1978) refutes the interpretation (by Stirling and scholars who followed him) that three fragmentary Olmec sculptures represent scenes of jaguar/human copulation. Kent F. Reilly III (1989) and others have persuasively argued that the many jade and stone figures with human/feline features represent images of shamanic transformation (rather than the progeny of interspecies sex).

In any case, Jiménez has substituted the automobile — an eroticized ritual object of modern industrial man — for the sacred Jaguar totem of the ancient Olmecs. According to Quirarte (1973: 117), Jiménez deemed human/animal coupling to be a “central theme” of world mythology. In conversations with me (and with many others), Jiménez noted that as a Jungian, he sought to tap into the collective unconscious, which he thought was the basis of universal mythic archetypes. Even before the artist had heard of Carl Jung, he believed in “the universality of certain images” (Jiménez, 1984). In the case of the so-called were-jaguar myth, however, Jiménez instead tapped into a Euro-American projection of European mythic structures that was mapped onto damaged Mesoamerican sculptures.

Cat Car serves as the apotheosis of Jiménez’s mechanical bridegroom. It is simultaneously an atavistic animal and the most technologically advanced of Jiménez’s mating machines. In this series, Jiménez takes hybridity to a new level by cryptically crossing species, sexes, myths, and machines.

Jiménez created a number of other sculptures that treat the merging of man/woman and machine in the modern industrial age. In California Chick (Girl on a Wheel) of 1969 (illustrated in Landis, 1994: 70), a naked blonde woman appears to be riding directly on a thick, stylized unicycle wheel — evidently very pleasurably, one might add. As in American Dream, she is receiving direct stimulation from the wheel, which in this case rotates between her breasts as well as her legs. Upon closer inspection, the wheel is too oblong to roll properly. This is because Jiménez originally pictured the woman on a motorcycle, which was compressed into a strange fat wheel (Jiménez, 1994: 70). The dark gray puffs at the bottom of the sculpture — including the ones on either side that envelop the woman’s ankles and feet and obscure the nature of her vehicle — are evocations of the exhaust from the no longer extant motorcycle. Jiménez cranked out slightly more sublimated female riders in a plethora of Rodeo Queens, all of whom ride high in the saddle and wield their breasts like six-shooters.

Jiménez restored the motorcycle in Cycle of 1969, with a presumably male rider, since the artist seems to conceive of motorcycles and bikes as extensions of men. A pencil sketch at Yale University from 1968 reveals how the artist conceptualized and broke down the individual components (the front part of the motorcycle is in yellow, the man in blue, and the lower part of the bike in red) before he merged them in the sculpture. The Yale drawing features an extremely large and fat front wheel and an elaborate exhaust pipe that resembles a chromium torpedo.

In a drawing from 1969 that corresponds closely to the sculpture (illustrated in Landis, 1994: 70), a helmeted, aerodynamic rider blends into the smooth, curving forms of a motorcycle. The front fender, front fork, frame, and gas tank have ballooned into a single, cloud-like enveloping form that is derived from the exhaust and wheel in California Chick. See the Cycle at Yale University. Jiménez must have preferred the more uniformly dark paint job of the version in his retrospective catalog (Landis, 1994: 71), which more seamlessly blends man and machine.

After he had secured the 1969 Graham Gallery exhibition (see Amaya, 1969), Jiménez began working on Cycle and other larger-scaled, related works (including Man on Fire and Barfly) that would appear in his second one-person show at Graham in 1970 (Perreault, 1970; Jiménez, 1985).

Jiménez provided a statement in the 1969 catalog that voiced social concerns. It is copied here in its entirety:

Art must function on many levels, not just one or two. The mechanics — color, form, etc., are important ingredients of art, but should not become ends in themselves. Art must relate to people. The most negated element or level in art now is the human one. Art should in some way make a person more aware, give him insight “to where he’s at” and in some way reflect what it is like to be living in these times and in this place (Amaya, 1969).

Amaya’s text, by contrast is flip and insouciant: “Whether his molded fiberglass ‘Candy’s’ are being ravaged by automobiles or whether they wait provocatively on the surface of the water to take on the fleet”; “Jimenez provides us with the delicious chance of wallowing in pure kitsch for its own sake”; “Virility and aggressiveness push his meretricious popular proto-types to the limits of their endurance” (Amaya, 1969).

Were he not listed as a collector of Jiménez’s work, one might think that Amaya disliked it. Amaya is at pains to dismiss the serious intent of Jiménez’s art: he instead emphasizes that it is naughty and fun and kitsch and there is no reason to take it too seriously. It is fantasy Pop, after all, Amaya (1969) concludes, no more believable than old myths:

One can accept Jiménez’s pop fantasies as completely as one might accept the Greek myths: his American Dream with its willing rape by a stud motor-car, is, after all, as viable as Leda and her Swan, Europa and the Bull, and the Shower of Gold.

From a marketing perspective, perhaps Amaya’s was the winning strategy, since the show sold out.

John Perreault (1970), in the catalog for Jiménez’s second one-person show at Graham Gallery, writes that his work is “too hot to be Pop.” Perreault admits that Jiménez’s fiberglass sculptures “made me re-examine my generally negative attitudes towards representational sculpture.” They elicited “emotional responses” in which he placed his “trust.”

Michael Ennis (1998) emphasizes the uniqueness of Jiménez’s work, and the degree to which it was out of synch with prevailing taste when he arrived in New York City in 1966 “with a stubbornly contrarian aesthetic” that was “outspoken, neon-hued figurative sculpture in an era of mute minimalist abstraction.” Little wonder that commentators were dismissive, flummoxed, confounded, or challenged to rethink their prejudices.

Perreault (1970) also noted:

One of Jimenez’s recurring themes is the merging — often erotic — of figure and object or machine. Last year’s American Dream depicted a lusty cutie entwined with a slug-like car. Black Cycle, [the name Graham gave for Cycle] this year, shows a male cyclist dissolved into his machine, becoming one with it, become its speed and its ominous death-sex symbolism.

Perreault was on to something. He recognized dimensions of seriousness and a darkness that Amaya dismissed. Actually, just a couple of years later, Jiménez’s Demo Derby (Pure Sex) perfectly corresponded to Perreault’s description of an “ominous death-sex” symbol. Note in particular the skull-like grill on Jiménez’s car. The phrase “pure sex” was inspired by an actual car the artist witnessed at a derby with that inscription.

Jiménez left New York in 1971 (Jiménez, 1984), around 1971, (Jiménez, 2007: 54) or in 1972 (Ennis, 1998) — I trust the earlier source, since it is much closer to the date of his return to the Southwest. Moreover, Jiménez (1985; 2007:54) states that he retrieved sculpture from a gallery that closed in Austin, and the only Austin show listed around this time in Landis (1994: 170) is in 1970. The O.K. Harris gallery was unable to provide the financing that Jiménez had expected. So he loaded up a borrowed truck with sculptures and trespassed on the posted land of the Roswell oilman and art patron who had apparently ignored his letter and who rebuffed his phone call when he was en route. That man was Donald B. Anderson. Jiménez was so broke that he had to dig up his own clay to make his models for End of the Trail. He also traded a fiberglass cast of Man on Fire for a used flatbed truck! Anderson became Jiménez’s patron for six years (Jiménez, 1985; 2007: 56-57). Anderson enabled Jiménez to become a public artist. As a consequence of his patronage, Jiménez was able to create End of the Trail, as well as the monumental and innovative Progress I (which required an incredible 50 individual piece molds) and Progress II. In turn, Jiménez paid Anderson with art, which is why the Anderson Museum has the world’s best collection of his work.

In a couple of instances, Jiménez also gave Anderson’s sculptures custom paint jobs. Disappointingly, Anderson’s Cycle is painted black, blue, purple, yellow-orange, gray, and the motorcyclist has a red-white-and-blue helmet with a star. This color scheme undercuts the melding of man and machine (and possibly exhaust) that is the aim of the work. This painting scheme serves to differentiate individual sections, transforming the work into a more conventional man on a motorcycle. As noted above Jiménez, must have preferred the paint scheme on the cycle illustrated in Landis (1994: 71).

Similarly, Anderson’s Demo Derby is greenish instead of smoky green-gray, and it has “Anderson Oil” painted on the hood instead of “Pure Sex.” For an illustration of a sex-and-death example, see Landis (1994: 68).

Continuing the man/mechanical theme in 1969, a drawing depicted a woman is giving birth to a machine-man. It seems to be an intermediary work between California Chick and Cycle and the audacious and remarkable Birth of the Machine Age Man. (For an additional related pencil study, see Landis, 1994: 73).

This sculpture features an aerodynamic mechanical being that is blasting headfirst out of the womb: it seems more like the launching of a rocket than the birth of a mere man. This newborn’s implicit motion is conveyed primarily through the tension of the woman’s arched body, whose lines of force extend to the tips of her fingertips. Birth of the Machine Age Man inverts the composition of the Cat Car: though the woman is on her back instead of her stomach, her arms likewise come to a point beyond her head. While the cat was stabilized by its mechanical wheels while it blasted upward, the woman’s arms and head provide stability while her mechanical child bursts out of her arched body.

Outfitted with a helmet/goggle head, this hybrid seems more machine than man. This supernatural birth is quite literally highlighted by a neon umbilical cord. A legacy of his father’s neon signs, it is the first of many neon elements in Jiménez’s sculptures. Because of the neon, gallery co-owner Robert Graham joked about showing it at Macy’s instead of the gallery. This quip angered Jiménez and he immediately switched from the Graham Gallery to O.K. Harris, a new gallery operated by Ivan Karp. Ironically, Karp didn’t like the sculpture, and he pulled it from the O.K. Harris opening (though he put it back in the show the next day).

In his AAA interview, Jiménez says this one-day exclusion made him go back to Graham for his next show (Jiménez 1985). But that statement is contradicted by the list of exhibitions in Landis (1994: 169-170): it has no exhibitions at Graham except a 1969 group show and the 1969 and 1970 one-person shows mentioned above; on the other hand, it lists four post-1970 one-person exhibitions at O.K. Harris. Jiménez (2007) also makes no mention of returning to Graham. So I think Jiménez misremembered or misspoke in 1985 (these off-the-cuff interviews are great sources of information, but they are also great sources of misinformation, as well).

In the AAA interview, Jiménez calls the decision to leave Graham “probably the biggest mistake I’ve made! Graham used to sell my work like hotcakes.” Graham sold to eminent patrons, such as Richard Brown Baker, who gave his outstanding Pop collection to Yale University (including three works by Jiménez), and Giovanni Agnelli, the owner of Fiat and Ferrari (who opened his own museum in Turin). At O.K. Harris, by contrast, sales were poor.

When it came to galleries, Jiménez was a hothead. Sometimes, as soon as he got a foot in the gallery door, he walked right out. Jiménez quit the Allan Stone Gallery because they put his sculpture under a coffee table in a group show. When he saw this placement at the opening, he walked right out with the sculpture (Jiménez, 1985). Landis (1994: 176) puts the Stone show in 1968, as does the 1969 Graham catalog (Amaya, 1969). Since Jiménez always wanted to be a public artist, he ultimately didn’t care that much about success in galleries. He had already reached a practical size limit with Cycle, which had to be crammed through Brown’s apartment door, which caused it to get scratched (Jiménez, 1985). Jiménez (2007: 54) felt the need to make even larger “public pieces that people could see without having to buy them.”

As for the Birth of the Machine Age Man, Jiménez mused: “nobody’s really wanted to show [it] very much” (Jiménez 1985). Undaunted by its lack of appeal to his gallerists, Jiménez considered Birth of the Machine Age Man the culmination of “everything I’d been doing” and thus one of his best sculptures “from the standpoint of forms.” He added: “I think it’s a beautiful piece. And I think it’s still a difficult piece to exhibit, because I think a lot of people just think it’s kind of gross subject matter” (Jiménez 1985). In the same interview, Jiménez also clarifies its meaning by referring to it as Woman Giving Birth to a Machine-Age God.

Unlike contemporary hyper-realist sculptors, such as John de Andrea (I was banned from Facebook for posting a de Andrea nude sculpture in 2018, which is how I began writing for Glasstire) and Duane Hanson, Jiménez was especially interested in exploring myth, symbols, technology, and consumerism. All three artists made tour-de-force renderings of models or social types, but Jiménez’s sculptures are extremely stylized rather than hyper-real. In some respects, he has more common ground with Tom Wesselman’s stylized evocations of consumer culture and Sexual Revolution. Jiménez said he needed to use fiberglass because it was “a statement in itself,” a material that could “incorporate color and fluid form, the sensuality that I like” (Jiménez, 1984). As noted above, he referred to it as a “working class” material.

Pre-Columbian Sources

Birth of the Machine Age Man has important Mesoamerican sources. Scholars have related this prodigious birth to that of Huitzilopochtli (Quirarte 1973: 117-118; Goldman 1994: 11; Lippard 1994: 25). When the Aztec patron deity Huitzilopochtli was born, he was fully-grown and attired for combat. His birth corresponded to the precise instant that his mother Coatlicue was murdered. Huitzilopochtli instantly wreaked furious vengeance on his matricidal siblings. On a symbolic level, we can assume that this mechanical man is also poised to meet any challenge.

“Aztec Grasshopper,” c. 1200-1521, carneolite, 7 ¾ x 18 ½ x 6 ¼ inches, Anthropology Museum, Mexico City. Photo: Anthropology Museum.

On a purely formal level, the streamlined form of the emerging male took direct inspiration from a remarkable Aztec sculpture. Though Lippard (1994: 25) did not specify which Aztec sculpture served as a model, she notes: “the compact form … was suggested by an Aztec grasshopper/cricket image.” The source must be the large grasshopper in the Anthropology Museum in Mexico City.

According to H. B. Nicholson (1983: 117), “This colossal grasshopper ranks as one of the most exceptional examples of monumental insect sculptures in the world. . . .” The fact that it has only four limbs endows the grasshopper with a more anthropomorphic quality. Nicholson notes that the presence of deity emblems on some grasshopper sculptures means that they probably had ritual significance (118). Grasshoppers had important material and symbolic connections to the Aztecs. They were a high protein food source in Aztec times. The grasshopper also served as the symbol and toponym of Chapultapec (grasshopper) Hill, a site that figured importantly in the mythic Aztec migration from Aztlán, which, according to late Aztec mythology, was divinely guided by Huitzilopochtli.

The aerodynamic shapes of grasshoppers enable long jumps and short flights. Furthermore, the hardness of the carneolite stone and the stylized compactness of the insect’s limbs and wings mitigate against breakage. Consequently, it should be no surprise that this grasshopper bears comparison to modern aerodynamic mechanical devices. Its “bug eyes” even resemble goggles. Thus even Jiménez’s most contemporary themes and aerodynamic forms can be traced back to ancient indigenous roots.

Critiquing the Statue of Liberty

Man on Fire is a human torch that can be related to the ideals of liberty that are often represented by the Statue of Liberty. Jiménez always treated the latter image in satiric fashion, as a drunken, degraded, over-the-hill emblem of corruption, decadence, and decline. The point of this critique is that the liberty that actually exists in the U.S. is so inadequate that for some people the symbol of liberty is a sham.

Fallen Statue of Liberty (illustrated in Landis, 1994: 59), a small statue crafted out of strips of soldered tin in 1963, depicts a corpulent, nearly naked liberty. She is so intoxicated that she has collapsed onto the ground. Jiménez also made a welded metal version that was ten-feet long (location unknown), which he sold for $200 (Jiménez, 1985).

In Statue of Liberty with Pack of Cigarettes, a drawing from 1969 (illustrated in Landis, 1994: 12), a naked or near-naked figure of liberty (she might be wearing panties) looks off in the distance while she holds a package of cigarettes. Jiménez, who had a very strict upbringing (no dancing or dating) in the Mexican Methodist church (often referred to as the Hallelujahs), was taught to have a very dim view of common vices, such as smoking and drinking, which is evident in this drawing and in the other works in this series. Jiménez sometimes surprised me, as when he disdainfully recounted that a famous critic had written that they had discussed his work while consuming beer. “I never discussed my work over a beer at a bar,” he told me.

Given Jiménez’s religious background, it must have been quite a cultural shock to arrive in New York City during the Sexual Revolution. Once that dam of sexual repression broke in New York City, the water never stopped cascading down. That accounts for Jiménez’s highly sexualized renderings of women, whether in ancient or modern subjects. I argue, for instance, that his danse macabre images, which feature nude women as personifications of death, represent a medieval frame of mind (Cordova, 2004: 28; Cordova 2019: 28).

Statue of Liberty with Wine features a woman in a tight-fitting orange mini-dress. The golden points of her crown blend seamlessly with her blond hair, which endows her with a racialized character. The “liberty” she dispenses is reserved for Whites. Jiménez recalled many instances of discrimination that he experienced. When he traveled with his father to places like Odessa, Texas, they were denied service at restaurants (Jiménez, 1985).

Liberty’s face is contorted in a very unappealing manner. Her tongue is out as she tries desperately to consume more alcohol, as if she were an animal dying of thirst, trying to lick up a few life-saving drops. But this lady is already so inebriated that she misses her mouth by a couple of feet and is instead spilling a copious amount of red wine on her lap. Jiménez is conveying the idea that “liberty” in the U.S. is determined and controlled by racialized elites who waste resources and who do not dispense freedom with equanimity. This personification of the Statue of Liberty, the very emblem of freedom in human form, is presented as a decadent, repellent, and racially exclusive figure. Though she tries hard to look appealing, she is drunk on her own power and profligate resources.

Luis Jiménez, “The Barfly — Statue of Liberty” (detail of liberty proffering her breast), 1969, fiberglass with acrylic urethane resin on painted wood fiberboard base, 90 x 36 x 24 inches, El Paso Museum of Art. Photo: Yelp

Jiménez’s critical reassessments of the liberty image culminated in The Barfly — Statue of Liberty (1969). A heavily made-up woman sits on a barstool. Her left hand is raised, but instead of liberty’s torch, she holds a glass of beer that overflows and streams down her arm. Instead of lighting the path to freedom, she salutes her own ongoing dissipation.

With her right hand, Lady Liberty cups and proffers her breast to the spectator. A U.S. flag extends from the front of her barstool to the floor. She is either sitting on the flag — intended as a disrespectful, drunken gesture — and it seems to be streaming from her genital region as if hung from an invisible pole, or she is sitting on a discarded flag dress. The latter would mean that she has disrobed to expose and offer herself sexually, essentially prostituting herself, whether for money or more beer. This action signifies the “prostitution” of liberty and justice. Perhaps Orozco’s cartoonish rendering of a sexualized and corrupt figure of Justice in his early fresco panel Law and Justice (National Preparatory School) served as a source of inspiration.

In any case, liberty’s apparel is so skin tight and skimpy that it can be read as underwear. But since Jiménez habitually garbed women in extremely tight clothes, it’s hard to be certain what he intended — or if he intended a degree of puzzling ambiguity. In any case, he has depicted prostitutes with more clothes than liberty is wearing.

Barfly was included in the quickly suppressed People’s Flag Show held at Judson Memorial Church in New York City in November of 1970, and it appears in the background of photographs taken by Jan van Raay of Abbie Hoffmann (wearing the flag shirt that caused his arrest in 1968), Kate Millet, and others at the opening, where Yvonne Rainer gave a nude performance of her dance Trio A. For a review of the exhibition, see Gleuck (1970). The exhibit was closed and three organizers (the Judson Three) were arrested for flag desecration. Like the organizers of the People’s Flag Show, Jiménez deliberately violated multiple aspects of the laws that demand “respect” for the flag (the flag touches the ground, the woman, her shoes, and the bar stool; it is possibly an article of apparel).

In the catalog for the 1970 Graham Gallery exhibition, critic John Perreault (1970) wrote:

Tits and the seven-foot, almost Breckinridge-ian Bar Fly [sic] … are as sexy in subject as they are in treatment. The smooth, rounded forms of these sculptures, the shiny finish that in some way contradicts the mass of the forms, and, in general, the soft-look of these hard works makes them as luscious as they are aggressive. (Perreault is referencing the 1970 film Myra Breckinridge, which starred Raquel Welch in skimpy, red-white-and-blue attire.)

Luis Jiménez, “Coscolina con Muerto (Flirt with death),” 1986, lithograph, 26 ¾ x 21 inches. Photo: YouTube.

A Jiménez lithograph, Coscolina con Muerto (Flirt with death), features a blond woman in a U.S. flag dress who is flirting with a skull-headed Nicaraguan Contra. He leans against a fortified wall with graffiti that reads: Chile, El Pueblo [the people], Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Los Mojados, C/S. Jiménez refers to several of the murderous, anti-democratic interventions made by the U.S. There is a close kinship between Coscolina and Barfly (Cordova, 2019: 61). I included Coscolina in an exhibition at the Centro Aztlán in San Antonio in 2004, and Jiménez identified the figure in the flag dress as “my Barfly/Statue of Liberty” in an email to me dated July 31. Consequently, our interpretation of Coscolina also applies to Barfly.

Coscolina explicitly links the U.S. to death. Most directly, the U.S.’s formidable war machine (and the financing that props up repressive regimes) always seems to be directed against people of color in developing nations. “Liberty” is attracted to murderous regimes (even if they play hard to get), and this racialized perversion of justice can also be understood in current domestic inequities, such as the fatal consequences of discrimination and poverty, as well as the use of deadly force against people of color by internal security forces. The border wall points to the conquest of half of Mexico and the injustices that ensued during and after the Mexican American War (terror, lynching, dispossession from land, segregation, discrimination). Jiménez’s concern with indigenous and African-descended peoples and the part they played in the genesis of Man on Fire is discussed below.

Significantly, while Man on Fire and Barfly are chronologically contemporary, on a symbolic level, they are antithetical visions of liberty. With every fiber of its being, Man on Fire burns as a beacon of self-sacrifice and the ideals of freedom. In Barfly, on the other hand, Liberty’s torch has been replaced by a foamy mug of beer that drips down Lady Liberty’s drunken arm. She is selfish and hypocritical, and is intended to represent moral decline. As a product of his strict religious upbringing, Jiménez viewed a barfly as “someone who was trying to go to hell, or something” (1994: 58). The Barfly motif mixes “personal history” with “an attempt to deal with the social situation” (1994:58). It signals Jiménez’s vehement opposition to the Vietnam War, which he expressed implicitly and explicitly (Jiménez 1994: 58; Brenson 1997: 13; Mitchell 1999: 101).

Orozco and Fire

Orozco, who was Jiménez’s favorite Mexican muralist, was so obsessed with fire that he included it as a dynamic and symbolic element in most of his murals. See: Harth (2001), Hurlburt (1989), Rochfort (1993), González Mello (1997), and González Mello and Miliotes (2002).

Man on Fire invokes Orozco’s obsession with fire and with Prometheus. The Greek titan was the subject of Orozco’s mural at Pomona College, painted in 1930. In Orozco’s view, Prometheus brought the gift of fire to an ungrateful human race and suffered eternal torment for this act of altruism.

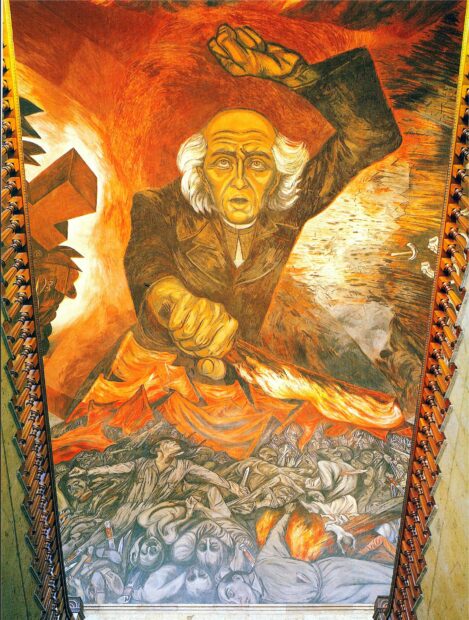

José Clemente Orozco, “Hidalgo,” 1937, fresco, Palace of Government, Guadalajara. Photo: González Mello and Miliotes, 2002: 236. Only the central part of the fresco is visible from this view, which is taken from the staircase.

In a remarkable wrap-around fresco at the Palace of Government in Guadalajara, Padre Hidalgo’s revolt unleashes an uncontrollable firestorm that completely encompasses the walls and ceiling of the palace (and, symbolically, of Mexican and world history).

In Gods of the Modern World (1932-1934), Orozco likewise rendered a veritable academic holocaust in the rare book reading room at Dartmouth College.

José Clemente Orozco, “Man on Fire,” 1937-1939, fresco, Cabañas Institute, Guadalajara. Photo: González Mello and Miliotes, 2002: 146.

Orozco’s most direct precedent for Jiménez’s sculpture, however, is the flaming apotheosis known as Man on Fire, in which a burning man ascends into the center of the cupola of the Cabañas Institute in Guadalajara.

When I first encountered Orozco’s fiery murals, I immediately thought of the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, a connoisseur of fire who reflected lovingly on fire in his book The Psychoanalysis of Fire (originally published in 1938). Knowing Jiménez’s interest in myth, symbolism, and Jung, I recommended the book to the artist, and he later told me he really enjoyed reading it. It is a difficult book to summarize, but this passage gives a taste of Bachelard’s insights:

Fire is thus a privileged phenomenon which can explain anything. If all that changes slowly may be explained by life, all that changes quickly is explained by fire. Fire is the ultra-living element. It is intimate and it is universal. It lives in our heart. It lives in the sky. It rises from the depths of the substance and offers itself with the warmth of love. Or it can go back down into the substance and hide there, latent and pent-up, like hate and vengeance. Among all phenomena, it is really the only one to which there can be so definitely attributed the opposing values of good and evil. It shines in Paradise. It burns in Hell. It is gentleness and torture. It is cookery and it is apocalypse. … It is a tutelary and a terrible divinity, both good and bad. It can contradict itself; thus it is one of the principles of universal explanation (Bachelard, 1964:7).

The Studies for Man on Fire

Man on Fire developed directly out of studies that addressed protests against the Vietnam War. The initial study features a drawing of a shirtless black or Puerto Rican man whose body twists as he prepares to launch a Molotov cocktail (Jiménez, 1994: 80, 82). His ethnicity and his blue jeans identify him as a protester in the United States. Jiménez had witnessed young men who threw Molotovs in New York City riots.

The artist was riveted by the sight of these half-bare men flinging flaming bottle-bombs. As a devotee of Jung, Jiménez told me that he came to believe that these men had struck a particularly resonant chord in his memory, specifically because they embodied a universal Promethean theme. This pencil on paper study, Jiménez’s first explicit exploration of the Man on Fire theme, is thus explicitly associated with Prometheus, the mythic giver-of-fire.

A subsequent series of studies treated Buddhist monks who immolated themselves in protest during the Vietnam War (Goldman 1994: 13). Self-immolation as a political act began in June of 1963, when senior monk Thich Quang Duc burned himself alive in downtown Saigon to protest the policies of the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese Premier Ngo Dinh Diem, who discriminated against Buddhists and favored the Catholic minority. U.S. president John F. Kennedy was deeply moved by the photograph of Duc’s self-immolation, and he urged reform. Diem instead declared martial law and raided Buddhist pagodas.

Four additional monks and a nun also self-immolated before South Vietnamese military officers staged a coup and executed Diem in November (after consulting with the U.S. government). Howard Jones (N.d.), who has also written a book on this subject, argues that the assassinations of Diem and JFK served to prolong the Vietnamese War (also see: JFK Presidential Library and Museum, N.d.; Sanburn, 2011).

With respect to subsequent protests, Josh Sanburn (2011) notes: “As the American presence increased in Vietnam in the mid- to late 1960s, more and more monks committed self-immolation, including thirteen in one week.” Jiménez (1994: 82) points out that “Vietnamese monks were burning themselves on T.V.” at the same time as the New York City riots.

The chile-shaped plume of flame in one of these studies of a self-immolating monk was retained in the final sculpture. (Chile is slang for penis in Spanish, providing another layer of meaning to the image.) Another study, which features a screaming immolated man, is executed in black, gray, and yellow pencils (illustrated in Landis, 1994: 83). Duc and some of the other monks made no sounds or motions as they burned to death, which is how Jiménez thought the Aztec Cuauhtemoc (see below) perished.

Jiménez, like many Chicano activists and artists, viewed the U.S. involvement in Vietnam as a racial issue:

I was very much against the war in Vietnam and what the United States was doing. I really saw it as a very…. I saw it as a racial kind of situation as well (Jiménez 1985).

José Clemente Orozco, “The Torture of Cuauhtemoc” (detail), 1950-1951, Piroxolin on Celotex, 4.53 x 8.14 meters, Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

While making these studies, Jimenez also made a connection with indigenous Mexico: the Spanish had tortured Cuauhtemoc, the last Aztec emperor, with fire, as in the Orozco detail illustrated above (Jiménez 1985). Cuauhtemoc is the stoic man with the turquoise diadem.

Whenever the young Jiménez cried due to a minor ailment, his grandmother noted that Cuauhtemoc had remained stoic, even when “they burned his legs off” (Jiménez 1985; 1994: 83). Jiménez mistakenly thought that Cuauhtemoc had been burned at the stake, rather than tortured to reveal the location of more treasure (Jiménez 1985 and 1994: 81). The important point is how Jiménez conceived of Cuauhtemoc: “I grew up knowing about this guy, thinking of him in a mythic kind of way. I mean, you know, this guy is like some kind of Superman” (Jiménez 1985).

In the final sculpture, Jiménez eliminated the Molotov cocktail and the references to the Buddhist monks, who sat in meditative positions while their bodies combusted. This kind of paring-down is part of his normal practice. The artist noted that he generally seeks to make images “more universal than specific” (Jiménez 1994: 80). The blue cylinder in the center of the base of the statue could be regarded as an unconscious reminiscence of the protester’s blue jeans. While it could also be interpreted as a canister for the flame’s fuel, Jiménez says he included it to “symbolize the machine/mechanical theme” (Jiménez 1994: 80). Thus Jiménez consciously inserted this detail as a confirming sign of thematic continuity near the bottom of the statue.

The machine/mechanical theme is further suggested by the flames that engulf the man’s head: they constitute a fiery aerodynamic helmet at the same time that they suggest streaming hair.

Man on Fire burns like Liberty’s torch. This sculpture encapsulates Cuauhtemoc’s torture and Prometheus’s supreme gift. It references the many Orozco murals that feature a troubled world consumed, transformed, and/or purified by fire. It was distilled out of anti-Vietnam War protesters on two continents. Additionally, it is transfigured into a mechanical man — a favored Jiménez theme.

A final drawing that is very similar to the statue features two plumes of flame, which can be read as wings. Red Angel, the subtitle of this drawing, suggests yet another frame of reference for the sculpture: Man on Fire can be viewed as a guardian, a supernatural being that transcends the terrestrial plane.

In the AAA interview with Jiménez, Peter Bermingham compared Man on Fire to the famous statue of Winged Victory in the Louvre. Jiménez affirmed this comparison and noted that the Hellenistic sculpture was “one of my favorite pieces of all times” (Jiménez, 1985).

In 1985, Jiménez did not recall seeing a three-dimensional example of this composition: he said he remembered it from an architecture class with his favorite professor at the University of Texas at Austin. In a 2004 conversation, I noted to Jiménez that he must have seen the large-scale plaster reproduction in the Academy of Fine Arts in Mexico City, where it still holds a prominent position. The artist, who made frequent trips to Mexico City, confirmed to me that he had seen it in Mexico City.

Significantly, the two plumes visible in Man on Fire, Red Angel strongly suggest wings and thus reinforce the association with Winged Victory. Moreover, the shading/hatching marks on the nearest plume in Man on Fire, Red Angel strongly suggest feathers.

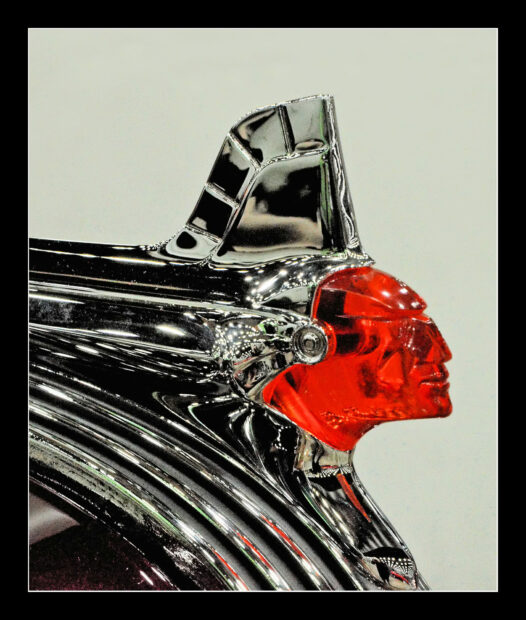

Pontiac Hood Ornament

1937 Pontiac Chief hood ornament. Photo: SoCal Cultures blog. Several other superb photographs of this ornament are available on the SoCal Cultures blog.

Jiménez stated in the Bermingham interview that another source for Man on Fire was the “Indianhead on my father’s Pontiac” (1985). Pontiac was a Chevrolet line that began production in 1926 from a factory in Pontiac, Michigan. The car and the city were named after the great Ottawa chief (1720-1769) who led a confederacy of tribes against the British in a prolonged conflict known as Pontiac’s War. Importantly for Jiménez, Pontiac — like Cuauhtemoc — was a proud and defiant leader of anti-colonial resistance.

Though Jiménez did not specify the year or model of the car whose emblem he imitated, Pontiac chrome or lucite hood ornaments featured sleekly stylized indigenous images for decades until 1957, when the Chief with Headdress was replaced with a stylized arrowhead logo. Irene Branson, Luis Jr.’s younger sister, indicated to me that Luis Sr. had many Pontiac cars in the 1940s and 1950s, and that he “usually switched cars out every couple of years.” So the possibilities are numerous.

Pontiac created some of the most elegant and beloved deco-inspired automobile embellishments.

Jiménez Sr. likely had an exquisite, early chrome hood ornament (and car) like this one, as well as more ordinary (and perhaps more realistic) ornaments. As a repeat customer, he no doubt appreciated the imagery and symbolism of many examples of this line.

Jiménez Jr. made vital use of his father’s hood ornament in what is arguably his most important statue. E. Carmen Ramos (2014: 209) notes that Man on Fire “holds a revered place in our institutional history since it is the first significant work by a Latino artist to enter the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s permanent collection.” When the Museo Alameda opened in San Antonio in 2007 with highlights from several Smithsonian museums, Man on Fire was one of the works chosen for its inaugural exhibition.

This illuminated Indian head car ornament morphs into a jet airplane. At the same time that it is an electrified component of an automobile, it is also a human/plane hybrid that anticipates Jiménez’s machine-age men, as well as his works that address progress.

This example is one of several Pontiac ornaments that morph from an Indian head into a plane. See the Just a Car Guy’s hood ornament guide.

Jiménez’s Progress of the West maquette (top) starts with a conquistador bearing a cross and an Indian hunting cattle. It ends with a locomotive overtaken by a car and a rocket. Jiménez always intended to do public art, and this work was inspired by 1930s murals (see discussion and illustrations in Landis, 1994: 94-95).

His Progress Suit of four lithographs from four years later similarly moves from a buffalo-hunting Indian to a Vaquero to a stagecoach, and finally, to a car, train, and airplane. The Pontiac ornament illustrated above is one of many such ornaments that make this transition from Indian to airplane in a single image.

Luis Jiménez,“Progress Suite,” 1976, lithograph, 23 ½ x 34 ½ inches, The Anderson Museum of Contemporary Art, Roswell, New Mexico. Photo: Dallas Museum of Art

In one detail, the vintage car in lithograph d has an airplane hood ornament. Numerous makes of automobiles — some of them very obscure — featured airplane hood ornaments. It is reasonable to assume that some family member or acquaintance had such an ornament. Again, see the Just a Car Guy’s hood ornament guide.

Indian imagery associated with the Pontiac automobile likely influenced Jiménez Jr. on a number of levels. They include complete — if highly stylized human forms — such as the Indian maiden. Pontiac also created neon extravaganzas with Indian imagery, such as the one linked here, though I don’t know if either Jiménez was familiar with them.

The red Pontiac Indian head logo is similar in color to Jiménez’s Man on Fire. Additionally, the three feathers that extend from the Pontiac Indian head are somewhat suggestive of the plume of flame in Man on Fire, which commences with a trio of lobe-like ridges at the top of the man’s head. They emerge into a hood-like form that flows into the plume that encapsulates the figure’s left arm.

The Pontiac Indian head connection adds additional layers of meaning to Jiménez’s sculpture. It references a famous, heroic leader, as well as a particular tribe from the present day United States. It also refers specifically to industrial vehicles that are hybridized with an exemplary indigenous man.

Conclusion

Roberta Smith’s summary of Jiménez’s sculptural work can also be applied to Man on Fire:

His surfaces are glamorized and artificial, with exaggerated forms that obliterate the difference between sensuousness and violence. Like certain advertising symbols and Art-Deco motifs, his figures seem to be speeding by and melting into liquid at the same time. Sometimes Jiménez’s people can seem like melodramatic caricatures in their cheapness and speed, but their extreme states are more complicated than that: in a peculiar way they are desperate and exposed, yet haughtily proud (1976: 48).

Man on Fire, of course, embodies and is fundamentally concerned with other qualities, including political commitment and self-sacrifice.

John Perreault (1970) likes Jiménez’s works because “they are complicated and tough.” He feels:

… they combine Pop, Radio City, and sometimes heroic iconography. But the sculptures are too hot to be Pop. The formality of Jimenez’s re-formulations of popular images, dreams, nightmares is wildly sensuous. These sculptures are low-down and sophisticated at the same time….

Dave Hickey argues that Jiménez “revivified the tradition of Mediterranean image-making and restored its faded glamor by reimagining it in contemporary terms and materials” (1997a: 8; 1997b: 24). This was accomplished by “uniting painting and sculpture in delicately balanced, dramatically cantilevered, [this is especially true of Progress II] free-standing objects that retain, somehow, the transparent luminosity of oil painting” (1997a: 8; 1997b: 25). This luminosity is not surprising, considering the many layers of paint (as well as glittering flake) that Jiménez applied to his fiberglass statues. His final three coats of clear finish in turn mimic the effects of varnish on oil paintings.

Hickey attributes Jiménez’s achievements in sculpture to his recognition that “the glimmering lowriders cruising the streets had already synthesized painting and sculpture,” for they were the “ultimate accommodation of solidity and translucency” (1997a: 8; 1997b: 25). Furthermore, Hickey believes the lowriders’ “smooth folds of steel and the hundreds of coats of transparent lacquer [that] caught the light and held it . . . like sleeves of liquid color” represent the Latino heritage of the Baroque. Incidentally, Jiménez greatly admired Bernini once he saw his work in person, though he had been taught that Bernini and the Baroque were “decadent” when he was in college (Jiménez, 1984).

As we have seen, Man on Fire emerged from many varied influences. Jiménez’s sculptures were often the product of a number of seemingly discordant strains of thought and artistic development. As he told Michael Brenson: “I think along several different tracks and when I arrive at an image, it’s kind of a synthesis of these various tracks that at one time seemed incongruous” (Brenson 1997: 13).

Man on Fire synthesizes diverse sources from Europe, Mexico, Vietnam, and the U.S. They combine high and low, East and West, North and South, indigenous and colonial, mythological and historical, and animal and mechanical. Jiménez revealed that this great sculpture possesses another level of meaning when he termed it a “spiritual self-portrait” (Jiménez 1985). In this context, I interpret the phrase to mean a symbolic representation of Jiménez’s ideals, rather than a physical likeness.

The face of this sculpture is an evocation of a generic (or should we say a Pontiac?) North American Indian, rather than a depiction of Jiménez’s own face. He does, however, state that his “deformed ribcage” is reflected in the statue:

I think maybe the Man on Fire is very appropriate, from 1969, as a kind of self-portrait. I used myself as the model. I don’t pretend to say that my face is like the Man on Fire; it’s not. I mean, I gave it very Indian characteristics, etc. But in fact there was something about it that was very much like, I mean, I used myself as the model in that. His ribcage, I have this very funny high ribcage. Anybody that sees the Man on Fire and says, “That’s not the way human ribcage is. . . .” I’m sorry; I have a deformed ribcage. My ribcage just goes cheeoo! straight across, and I’ve got a chicken bone right there (Jiménez 1985).

Man on Fire represents the artist not by imitating his facial features, but by summing up his artistic and political allegiances, convictions, and aspirations. In this most personal of works, the artist’s passion, creativity, and hunger for justice continue to illuminate us all.

Appendix: Bronze Version of Man on Fire at the McNay Museum

Luis Jiménez, “Man on Fire,” 1969/99, cast and patinated bronze, 89 x 60 x 19 inches, Marion Koogler McNay Museum, San Antonio. Photo: McNay Art Museum

In 1998, Jiménez told Texas Monthly: “I decided that if my images were going to be taken from popular culture, I wanted a material that didn’t carry the cultural baggage of marble or bronze” (Ennis, 1998). As noted above, fiberglass as a medium permitted Jiménez to achieve the effects of sensuality, color, and fluid form that he was seeking.

Just one year after talking to Ennis, however, Jiménez made a bronze cast of Man on Fire. He appreciated how Julio González and Alexander Calder used iron and steel (Jiménez, 1984), and Jiménez must have felt that Man on Fire, like Howl, was a simple enough composition to be cast in bronze. Equally important, he must have thought that it would look good in bronze. The greatest physical advantage of bronze is the material’s longevity. Unlike fiberglass, it lasts for thousands of years with little maintenance. Additionally, Jiménez made small editions of his fiberglass sculptures (often only five), so an edition in bronze would allow him to double the number of casts.

Purchased by the McNay in 2013, this was the only cast of Man on Fire made during the artist’s lifetime, and the McNay staff believes it is still the only one in existence.

I show a rear view here because this side of the statue is rarely illustrated.

Bronze sculptures are usually 90% or more copper, and when they are new, they have the sheen of a bright, new penny. Consequently, artificial patinas (a finish on the surface of the bronze caused by chemical reactions) are applied to statues. It is this subtle patina (compared to Jiménez’s bright, polychromed fiberglass sculptures) that is responsible for the subdued colors evident in the sculpture.

For the process of applying patinas to bronze, see Bronze Sculpture Patinas and the Adonis Bronze video.

Note how prominent the figure’s chest looks without the bright colors of the fiberglass versions.

Jimenez’s man wears a veritable cloak of flame as he becomes transformed into a crucible of fire. As Bachelard (1964: 57) writes, once again in the Psychoanalysis of Fire: “Through fire everything changes. When we want everything to be changed we call on fire.”

Bibliography:

Amaya, Mario. 1969. Untitled essay. Luis Jimenez. New York: Graham Gallery.

Bachelard, Gaston. 1964. The Psychoanalysis of Fire. Translated from the French by Alan C. M. Ross. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Brenson, Michael. 1997. “Movement’s Knowledge,” in Luis Jiménez: Working Class Heroes, Images from the Popular Culture. Kansas City, MI: Mid-America Arts Alliance: 11 – 20.

Cordova, Ruben C. 2004. ¡Arte Caliente! Selections from the Joe A. Diaz Collection. Corpus Christi: South Texas Institute for the Arts.

_____. 2019. The Day of the Dead in Art. San Antonio: City of San Antonio, Department of Arts and Culture.

Coe, Michael. 1965. The Jaguar’s Children: Preclassic Central Mexico. New York: Museum of Primitive Art.

Coe, Michael, et al. 1996. The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership. Princeton: Art Museum, Princeton University.

Davis, Whitney. 1978. “So-Called Jaguar-Human Copulation Scenes in Olmec Art,” American Antiquity 43, #2 (July): 453 – 7.

Ennis, Michael. 1998. “Luis Jiménez,” Texas Monthly, 26, #9 (September). (I consulted an unpaginated PDF provided by the San Antonio Library.)

Flores-Turney, Camille. 1997. “Howl: The Artwork of Luis Jiménez,” in Howl: The Artwork of Luis Jiménez. New Mexico Magazine Artist Series: 11 – 68.

_____. 1994. “Luis Jiménez: Recycling the Ordinary into the Extraordinary,” in Ellen Landis, et al, Man on Fire: Luis Jiménez. Albuquerque: The Albuquerque Museum: 7 – 20.

Gleuck, Grace. 1970. “A Strange Assortment of Flags Is Displayed at ‘People’s Show,’” New York Times, November 10, 1970. https://www.nytimes.com/1970/11/10/archives/a-strange-assortment-of-flags-is-displayed-at-peoples-show.html

González Mello, Renato. 1997. José Clemente Orozco: Pintura Mural. Mexico: CNCA, 1997.

González Mello, Renato, and Diane Miliotes, eds. 2002. José Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927 – 1934. Dartmouth: Hood Museum of Art.

Harth, Marjorie. 2001. José Clemente Orozco: Prometheus. Claremont: Pomona College Museum of Art.

Hickey, Dave. 1997a. “Luis Jiménez and the Incarnation of the West,” in Howl: The Artwork of Luis Jiménez (New Mexico Magazine Artist Series): 7 – 10.

_____. 1997b. “Luis Jiménez and the Incarnation of Democracy,” in Luis Jiménez: Working Class Heroes, Images from the Popular Culture. Kansas City, MI: Mid-America Arts Alliance.

Hurlburt, Laurance P. 1989. The Mexican muralists in the United States. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

JFK Presidential Library and Museum. N.d. “Vietnam, Diem, The Buddhist Crisis.” https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/vietnam-diem-the-buddhist-crisis

Jiménez, Luis. 1984. Amy Baker Sandback, “Signs: A Conversation with Luis Jimenez,” Artforum (September). https://www.artforum.com/print/198407/signs-a-conversation-with-luis-jimenez-35349

_____. 1985. “Interview with Luis A. Jiménez, conducted by Peter Bermingham,” Smithsonian Archives of American Art. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-luis-jimenez-13554

_____. 1994. “The Process of Developing a Sculpture” [and miscellaneous untitled commentaries in plate section of catalog], in Ellen Landis, et al, Man on Fire: Luis Jiménez. Albuquerque: The Albuquerque Museum: 48 – 52; 53 – 168.

_____. 2007. “Luis Jiménez (1972-73, plus five more years),” in Ann McGarrell, Sally Anderson, and Jonathan Williams, The Roswell Artist-in-Residence Program: An Anecdotal History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Jones, Howard. N.d. “JFK Wanted Out of Vietnam,” History News Network. https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/3446

Landis, Ellen, et al. 1994. Man on Fire: Luis Jiménez. Albuquerque: The Albuquerque Museum.

Lippard, Lucy R. 1994. “Dancing with History: Culture, Class, and Communication,” in Ellen Landis, et al, Man on Fire: Luis Jiménez. Albuquerque: The Albuquerque Museum: 21 – 38.

Mitchell, Charles Dee. 1999. “Luis Jiménez: A Baroque Populism,” Art in America (March): 100 – 105.

Nicholson, H.B., with Eloise Quiñnones Keber. 1983. Art of Ancient Mexico: Treasures of Tenochtitlan. Washington: National Gallery of Art.

Perreault, John. 1970. [Untitled essay.] Graham Gallery. New York: Graham Gallery [exhibition catalog for Luis Jiménez’s second one-person show].

Quirarte, Jacinto. 1973. Mexican American Artists. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Ramos, E. Carmen. 2014. Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art. Washington, DC: Smithsonian American Art Museum, in association with D. Giles Limited, London.

Reilly, F. Kent, III. 1989.“The Shaman in Transformation Pose: A Study of the Theme of Rulership in Olmec Art,” Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, 48, #2: p. 4-21.

Rochfort, Desmond. 1993. Mexican Muralists: Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Sanburn, Josh. 2011. “A Brief History of Self-Immolation,” Time, January 20, 2011. http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2043123,00.html

Stirling, Matthew W. 1955. “Stone Monuments of Rio Chiquito, Veracruz, Mexico,” Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 157: 1 – 23.

Yau, John. 1994. “Looking at America: The Art of Luis Jiménez,” in Ellen Landis, et al, Man on Fire: Luis Jiménez. Albuquerque: The Albuquerque Museum: 39 – 47.

***

I touched on much of the material in this article in a lecture called “American Dreams” that I gave while serving as a consultant for the establishment of a Chicano Studies program at the El Paso Community College in 2007. I developed it into a crisp half-hour talk on Man on Fire that I delivered in twenty minutes at the Latino Art Now! conference in New York City in 2008. I gave lengthier lectures at Queens College in 2009 and at the Center for Mexican American Studies, University of Houston in 2010.

Ed note: select images have been removed from this article at the request of the Luis A. Jimenez, Jr. Copyright Trust.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator who has taught Jiménez’s work in his courses at the University of California at Berkeley; University of Texas, Pan American; University of Texas at San Antonio; Sarah Lawrence College; University of Houston.

8 comments

Ruben Cordova’s deeply insightful and wonderfully researched essay is a reminder of how much Luis Jimenez has enriched our lives through his magnificent work. It is an ongoing tragedy that he left us far too soon. Thank you, Mr. Cordova.

Great article on one of our Grandmasters of Art. Bravo!

You are most welcome, Mike. Luis is sorely missed.

Another in-depth sensitively researched and written piece by Ruben Cordova!

Capturing the creative & unique passion of master Luis Jimenez!

I grew up with the early El Paso Jimenez magical neon & sculptural signifiers from his father’s studio shop. Luis’ perfect training ground that gave us a man on fire, indeed!

Ruben, thank you for your article on Luis. Him and Mel were my two mentors that played a big roll in my development as an Artist. Your essay brought back memories of Luis and thing I didn’t remembered of his early years. Really appreciate your essay, thank you again. gaspar

Thanks, Roberto. I will be writing at least two more articles on Jiménez.

Celia, why don’t you share your memories of the signs and of Luis’ early days here in the comments section?

You are most welcome, Gaspar. I wanted to give the fullest account of the evolution of Man on Fire. I knew you were close to Luis, but I didn’t know you were close to Mel as well. Mel seems to have known everyone.