Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

I first met Josue Rawmirez in the summer of 2017 when I was visiting the Rio Grande Valley during a road trip as part of my curation of the Texas Biennial. While Josue is one of a few practitioners working in the contemporary art ecosystem in Brownsville, his tenacity has been unwavering, despite challenges and setbacks. Rawmirez has remained committed to the Rio Grande Valley and has invested his time personally and professionally in the border region, a place that continues to be a protagonist in his work and practice both in object-making, and in a social practice that involves celebrating the culture of the border and the Rio Grande Valley overall.

I had the pleasure of catching up with Rawmirez recently. We talked about his practice and all the initiatives he has his hands in, including Trucha, a multimedia organization in the Río Grande Valley that is now celebrating its first year anniversary.

Leslie Moody Castro (LMC): When you and I met in 2017, you were working on a series of works that played on translations of pop culture. Things like Disney (Mickey Mouse ears made with oilcloth, nopales, and sarape fabric). You were touching on how popular cultural items don’t necessarily translate the same ways for all cultures. Can you tell us a little bit about how you were thinking about culture then and how it has evolved for you over the years and until today?

Josue Rawmirez (JR): In 2017 I had been out of UT Austin for a few years and had settled back into the Rio Grande Valley after a quick stint in Los Angeles. I was exploring the region in new ways including through street art and muralism, and I thought about culture through a centered lens of my Mexican American experience and studies.

I remember seeing Dewey Tafoya’s Aztec Falcon screen print in LA at an event at the Watts Towers and it really struck me. I was inspired to make art that intermixed obvious cultural signifiers, but I wanted to incorporate my queer immigrant experience and challenge certain notions and assumptions behind the imagery.

For example, in a series of work called Borderlands, I used the Disney universe to speak about utopias, the “American dream,” and what that would look like along the frontera. I placed Disney artifacts and characters in traditionally Mexican spaces and with iconography like the zarape, the loteria, nopales, conchas, Aztec art, etc. It was very Pop art inspired and a little superficial, but looking back my thoughts on culture were that too. To be honest, I didn’t think much of culture other than making art and being a little subversive.

I also worked with grassroots community groups on issues around infrastructure, housing, and immigration, where I shared my artwork for campaigns. I learned the power of organizing and the role of art within that. My perspective on culture changed completely when I was introduced to cultural organizing and the idea that creativity and the arts are the basis for movement building and cultural shifts, that creativity should be centered on these important societal issues and the efforts to address them. My knowledge about the power of culture, and inherently of storytelling, is something that has definitely evolved since then.

I’ve met with amazing creatives and cultural workers who motivated me to have these conversations with my community. To take the challenge of helping to shift the cultural narrative of the region in a more holistic one that centers social justice. I definitely feel compelled to do that in my multidisciplinary practice today.

LMC: Since we met, you have also broadened your practice to include sculpture and performance. How has stepping into different mediums helped to communicate what you are interested in exploring with your work, and what has the process of experimentation been like?

JR: I’ve found freedom in the title of multi-disciplinary artist and in social practice — more bang for your buck! Joking aside, I like to explore ideas or concepts through different mediums so as to expand and tell a more rounded conversation on the subject. My dive into sculpture and performance were part of that exploration. The process of experimentation has been great. During the pandemic I casually picked up ceramics, made good friends, and am now taking ceramic classes at the local community college. Performing particularly has been really fun — it gets the endorphins flowing which is always good. It’s a callback to the high school thespian in me and an ode to my love for choreography and dance — though I don’t think I’m particularly good at either!

LMC: The piñata and piñata paper have become a staple in your practice. Can you talk about why this material is significant to you?

JR: The piñata and I go back a long way — as it does for many other Latinx folks. I began exploring it as a medium and a theme in my work as a reaction to the Donald Trump piñatas that were destroyed in effigy during his election. It took me down a long craft rabbit hole and I emerged with a new understanding and interpretation of the cultural icon. I want to draw attention to the aesthetic, the practice, and the repetitive patterns instead of the symbol or iconography. I used abstraction, expressionism, and psychedelia to develop what I call Piñatabstract. It expanded to include large sculptures, installations, wearable art, and performance. Through that work I learned of other piñata artists including Giovanni Valderas and Justin Favela whom I became a huge fan of. I curated a three-person show, Piñatasthetic, with them at the Houston Art League Houston in 2020 before the pandemic.

I continue to interact and explore the piñata and its meaning in our collective imagination, though now I’m focusing on the mediums of ceramics and papermaking. Last year I was part of an amazing show at the Craft in America Center titled Piñatas; The High Art of Celebration that was a fantastic curation of artists continuing and expanding the piñata tradition. It was great to be a part of it. I think it is something that I will continue to explore in the future.

LMC: Brownsville and the border region of the Lower Rio Grande Valley are integral to you personally and your artistic practice. Can you tell us why you have chosen to stay so committed to the Valley and what challenges you have faced?

JR: It would be easy to say it’s because I grew up here, but like many recent college graduates I didn’t have much lined up as far as employment perspectives after graduation, and was lucky enough to be able to move back home. Shortly after I landed a great role with Texas Housers, a fair housing advocacy organization and I moved to the Upper Valley. I went from policy analyst to Rio Grande Valley Regional Co-Director. It was one of the best roles and careers. I learned integral life lessons and made impactful changes in the region through new laws, homes, infrastructure etc., and in individuals lives. That lasted seven years and allowed me to really build community among like-minded organizers, creatives, and activists.

Those relationships have grown through the challenges of the region and translated into a commitment to one another and our home that is often unspoken but unwavering. Obstacles in the border are not difficult to find, and as creatives they are abundant. Living as a working artist is difficult, considering the lack of opportunity and resources we face regionally. A challenge I faced was leaving a comfortable and amazing organization to what seemed like a one of a kind and unique opportunity in the arts that ultimately did not pan out. It shifted my life’s trajectory and taught me many things the hard way. I hope that I am better because of it now.

LMC: What about victories?

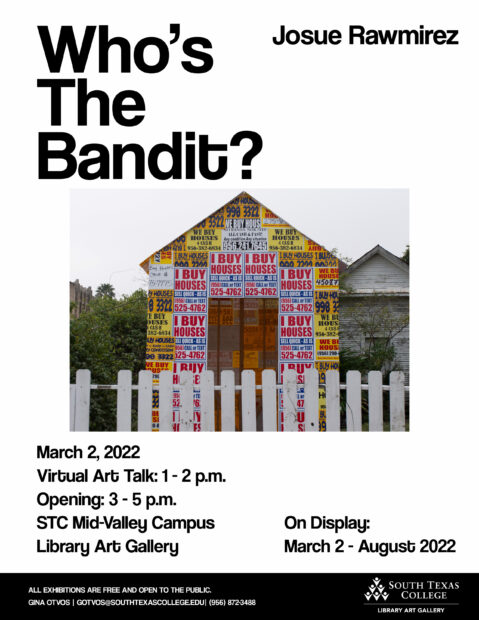

JR: As an artist I’ve had some awesome victories, including some nice mentions on some cool publications like Pitchfork, Remezcla — I was #1 on Glasstire’s Top Five! I’ve gotten to meet and work with Giovannini Valderas and Favy Fav, who I was a big fan of from Latinos Who Lunch (Que en paz descanse LWL, since it is no longer active). I’ve been invited and considered for some opportunities that were life changing, meeting amazing artists who I am in awe of — all of these are victories in my book. Participating in Luminaria and performing at the Helado Negro concert at Cine El Rey were also big moments. Being published by the New York Architecture League was cool too. My introduction to ceramics was a win. I have a solo show at called Who’s the Bandit? at the South Texas College Library Gallery on March 2 that I am excited about. Also, Trucha and all things related to that.

LMC: Talk about Trucha, what is it and what was the catalyst to starting it?

JR: Trucha is an independent multimedia organization and platform dedicated to the people, the culture, and social movements of the Rio Grande Valley, centering queer and migrant communities of color. We create and curate audio, video, writing, multimedia projects, and community events to craft a more nuanced and holistic narrative about the Rio Grande Valley.

Our mission is to inform our readers, inspire our community, and build a collective infrastructure to proudly cultivate and showcase the authentic stories and the creativity of our community through a grassroots narrative of the frontera. I am the co-founder and Cultural Organizer.

Trucha came from what was previously called Neta, created in 2017 by a collective of artists, organizers, and journalists. The group developed quickly and gained a strong reputation for its reporting on immigration, reproductive justice, and arts and culture. I supported the arts sector and secured funding to take a full-time role. I quit my job and took it on as a new venture.

Unfortunately, shortly thereafter, the collective fractured and faced organizational issues with worker grievances. Management stepped down forcefully, funding fell through, and our fiscal sponsorship was terminated. The arts funding was pulled, and I was forced to leave and worked on a contract basis while others tried to restructure and reorganize, but that ultimately failed. The platform was left to be run voluntarily.

Together with a colleague and a past member of Neta, we decided to try to recuperate the platform and the resource to the community. We secured funding and took on a multi-year process of acknowledgement, healing, nurturing, and rebranding along with other community members who helped. We launched in February 2021 as Trucha and just celebrated our first birthday. We are chugging along steadily.

LMC: Can you explain the name, Trucha?

JR: On our site we describe Trucha [tru-cha] as a verb that is a means of survival and resilience where one is aware of their surroundings for themselves and their community. “Ponte Trucha” is a vernacular saying in the Valley and in Latinx community and — although it varies regionally — here it is said as a warning or as a phrase to liven one up and get them to be more attuned to what’s around and their situation. For those who don’t know the slang, it might seem weird since “trucha” translates to trout, the fish. That would explain why it is also slang for gay or queer, which we take as a compliment since we prioritize the queer and immigrant community. But we are no “pescaditos” [small fish], and it’s not even our mascot. The “chicharra” or cicada is part of our brand because we shed the past. We want to be loud. We want to sing and let our truth ring. So that is the deal with Trucha. If you don’t get it you’d have to do some research, but if you get it right away then we are sure you will like what we are up to. “Ya sabes.”

LMC: How has Trucha evolved in the year it has been running (congratulations on that anniversary), and has it also become a part of your practice as an artist?

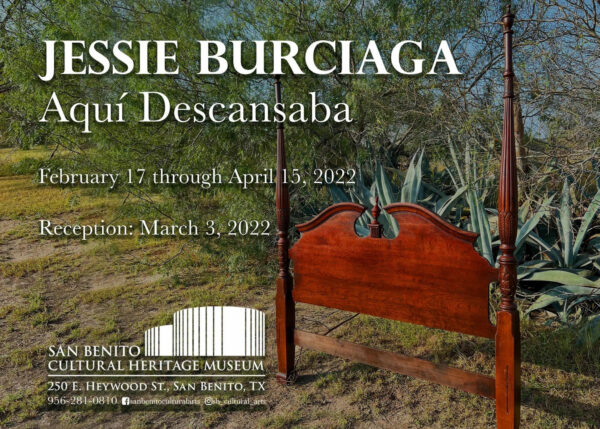

JR: Thank you! Since our launch, Trucha has evolved to be more on the movement-journalism side in our articles and videos. We also include creative and cultural programming activities as well as events. Last year we received the NALAC and Ford Foundation Border Narrative Grant, which allowed us to create the De La Casa Digital Artist Residency and put on a group exhibition at the San Benito Cultural Heritage Museum that included artists Sam Rawls, Monica Lugo, and the Frontera Dance Company, as well as photographs by Veronica Cardenas. We supported a summer arts program for colonia youth with about 20 kids from ARISE Adelante, a social service organization focusing on women and children. The Miraaa Multimedia Festival was developed in collaboration with artists Andres Sanchez, C Diaz, and Natalia Rocafuerte. It featured over 40 local artists and videographers working on experimental and noncommercial art. Trucha’s most recent show is the solo exhibition Aqui Descansaba by Jessie Burciaga, which touches on his experience with loss and the missing of family due to border violence.

Additionally, Trucha has collaborated with other artists and social justice organizations on creative workshops and actions surrounding rental assistance, SpaceX encroachment, and reproductive justice, to name a few. We cover local creatives, artistic happenings, and engage in cultural critiques, all in addition to our editorial work on social issues and new media creation like GIFs, digital illustrations, memes, etc.

I definitely consider the cultural organizing at Trucha to be part of my practice, because I am purposefully and actively engaging in this work; I write, edit, fundraise, and make art along with others. We create a holistic understanding of our local experiences that fights back against the dangerous narratives of our region as told by others. Along with trusted colleagues, we are building a resource and part of the creative infrastructure that our community deserves, and we are doing it on our own terms.