To read Part 1 of this series, please go here. To read Part 2, please go here.

Over the last two years I have been thinking more about the roles of women — about their stories, and about how I have been influenced by them. As I trace my own ancestry through my grandmother’s story, I have been pulled into the mystery of my great-grandmother, and as I spent more time in Narva, this Estonian border town between East and West, the pull to understand more about her life — or what could have been her life — became more attractive. Thinking about the lineage of women in my family, I started contemplating names and the power that we, as women, have lost by relinquishing them; about how histories and stories are carried on through the lines of patriarchs; about how we forfeit our agency, which forever changes the ways our histories can or cannot be found.

It is impossible to separate my own interests, history, and ancestry with the history of Narva as both a place and a culture. The border here is a winding river that separates two countries, which can be crossed by a series of bridges. Each side is lush with green foliage and wildlife, growing equally wild on both sides. There is a similarity in the geography and the heat and humidity that makes Narva so similar to the border of San Benito and Brownsville. It was similar to the point of being eerily familiar. Even the defunct Kreenholm Factory, sitting on an island in the middle of the river like a monument, felt like the maquiladora of an era long gone, or perhaps a monument to history repeating itself.

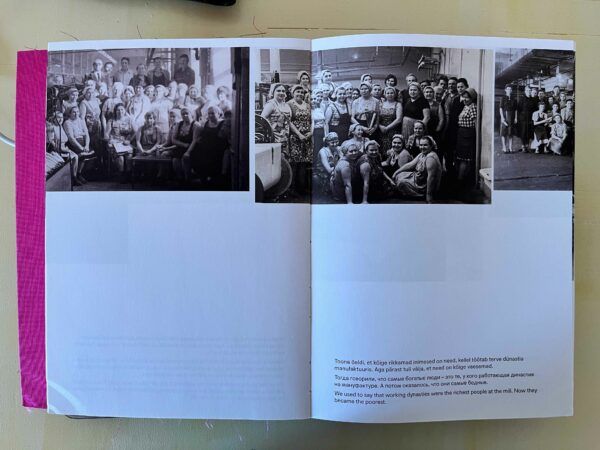

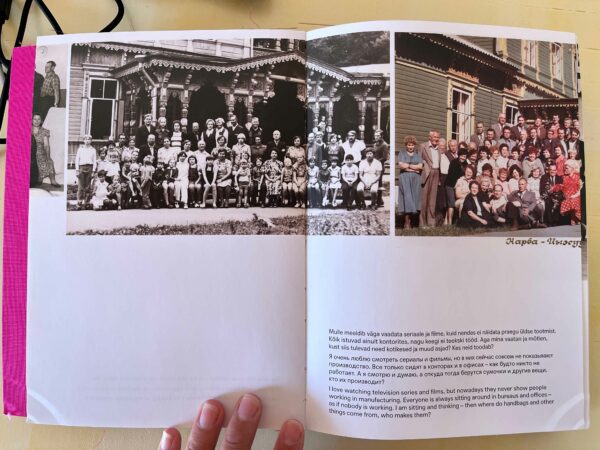

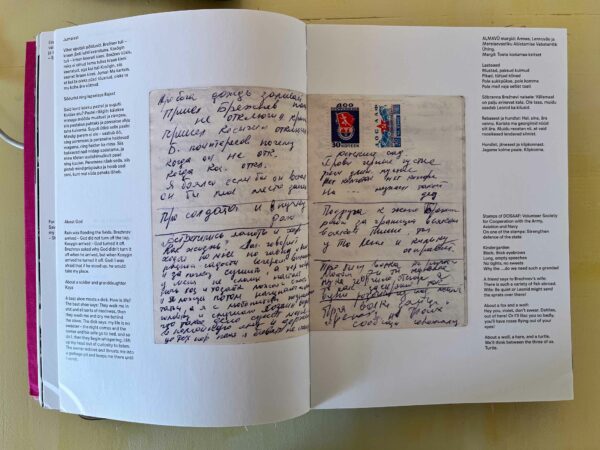

But the thing that always shook me from my nostalgic, geographic daydreams of being lost between places was that this factory in Narva (or original maquiladora) also established a seamlessness between the borders, which is reinforced by the strong matriarchal presence that still lingers in the region. At one point the factory — the largest in Europe — employed up to 10,000 people, most of whom were women. The stories of the factory, and of the role of women in Narva, were the subject of an exhibition by artist Marja Kapajeva. The exhibition, titled Dream is Wonderful, Yet Unclear (translated from the original Russian), tells the artist’s story of her relationship with Kreenholm while growing up in Narva. The historical images accompanying this text are from the artist’s exhibition catalog.

What we know of the soviet era in the west is far different from what the real story was. Estonia was a colonized and controlled country for decades, and as the brutality of the Soviet Union increased as its collapse became imminent, Estonia actually gained its independence and was ejected from the confederation before the Soviet Union folded. But before that, there was a golden era of the Soviet Union (there are still people alive who remember this time) where the concept of the country actually worked: the population had enough, and there was a stronger sense of equality in the masses. And when the Kreenholm Factory was in its heyday, it was a place that worked because of the labor of women. That said, what looked like equity wasn’t necessarily equal, and while women did their fair share of labor, they were also still expected to tend to the home and the children, which was not considered labor. So, by our current standards of equity, women carried the lion’s share of work.

Kreenholm is massive, and it takes walking through the site and into the abandoned buildings to really understand the scale at which it operated. This was a city inside of a city; it had its own hospital, pharmacy, store, school and dormitory-style housing for employees. Ten of those dormitories were built specifically for the women who worked in the factory.

I was lucky enough to have an afternoon to sit with former factory employees — a group of 12 women and one gentleman participating in a photography workshop at the library in Narva, a program created and supported by the U.S. Embassy. This wasn’t just a photography class, however — I was impressed to learn that this workshop was focused on helping older people learn and navigate smartphones through teaching them about phone cameras. On top of that, it was also a social hour for each participant, as well as a way to bridge generational gaps in technology. And it turns out, the participants were all really good amateur photographers.

We only had about half an hour to chat, but in that short time the quickness at which each person in the room swelled with pride about the seamlessness of their border (and their relationship to Kreenholm) was obvious. (We were also joined by Jekaterina Moisejeva, who interpreted my questions and the participants’ answers. In Narva, the dominant language is Russian, and I do not speak a word of Russian.)

Each woman in the workshop was excited to tell the stories of how they once worked in the factory in one capacity or another, how their mothers, aunts, cousins, and grandmothers had also worked in the factory, and how all the labor of the town of Narva was really divided up amongst women. All to say that the economy of Narva at large was supported by the labor of the women who made the textile mill run. There was a deep sense of pride in the role of the women, which included the action of working for a greater goal and creating, sustaining, and being part of a community that relied on all of its members to function.

Our conversation during the workshop wasn’t clear-cut — my visit was last minute, and I didn’t need clear answers, only lingering sentiments. As the women verbally stumbled over each other to share their stories with me, they were curious about my life and the ways in which I traverse borders. They were fascinated to know that geographically — at least in the summer — our places look very similar. They were also curious about the militarized zones, the building of a border wall, and the ease at which people can or cannot travel across the U.S.-Mexico border. This is a relatively new phenomenon for them; living in Narva, coming of age in Kreenholm, and actively participating in sustaining the economy of a country meant a seamlessness between here and there, and this new decade of division with border agitation from the Russian side meant a new type of separation they hadn’t lived before.

It was no wonder that in my short time in Narva I had become drawn to the story of my great-grandmother, Fanny. The presence of matriarchs was surrounding me. I was in a city that survived because of the economy, power, and labor of its female population. But it was the generations of women who passed the torch and the strength and ties to their memories that seemed to draw me in even further.

That’s what I wanted to find in my own lineage.

My great grandmother, Fanny Nagurney, holding my paternal grandmother, Ann Nagurney. This is the only image I have seen of Fanny

All photos by Leslie Moody Castro

****

Special thanks to Tiiu Vitsut, Filipp Mustonen, The Office of Public Affairs at the U.S. Embassy, Tallinn, Ann Mirjam Vaikla, the NART Narva Artist Residency, and especially to Jekaterina Moisejeva for her incredible interpretation skills. Thank you to my cousins Carol Franco, Brian Nagurney and his father John Nagurney, Aunt JoAnn Villarreal, Aunt Jeannie Cisneros, and Aunt Betty Moody Winters.

1 comment

What a wonderful journey you’ve had. Aunt Betty resembles our grandmother , Fanny. I remember her last visit to San Benito. She took the train from Philadelphia to San Benito. She always brought us presents with every visit. She died shortly after her last visit. She was in an automobile accident near her home in Chalfont, PA. Nana Moody was about 33 Years old when her mother passed.