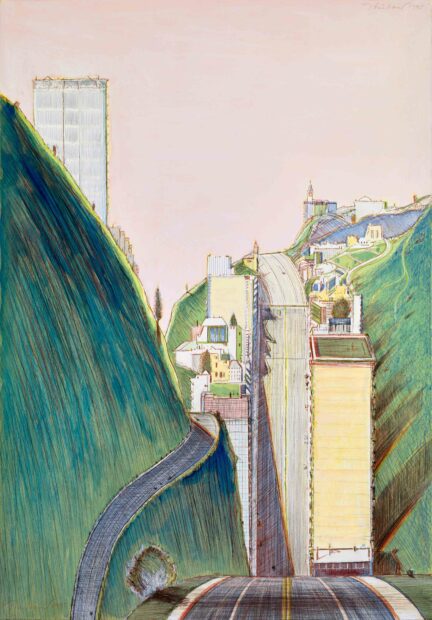

Wayne Thiebaud, Park Place, 1995. Color etching hand-worked with watercolor, gouache, colored pencil, graphite, and pastel, 29 9/16 x 20 3/4 in. (sheet/image). Crocker Art Museum, gift of the Artist’s family, 1995.9.50. © 2021 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

This review was never meant to be an obituary. I began composing it in my head, in early December, the moment I stepped into the McNay Art Museum’s exhibition Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings. Billed as a celebration of Thiebaud’s “100th birthday through 100 works representing the artist’s achievements in all media through an array of subjects,” the show did not disappoint. In Glasstire’s “Best of 2021,” I wrote that the exhibition is “chock-a-block with some of the slickest paintings I’ve ever seen.” I resisted the urge to begin that bite-sized capsule review with the line I really wanted to use: “Wayne Thiebaud may very well be the best painter alive today.” Instead, I figured that’d be a snappy opener to this article. Sadly, that sentence is no longer true.

Thiebaud died on December 25th — Christmas day — at the age of 101. The fact that he was alive (and still working) in itself was remarkable. His generation of artists is that of myth and legend; they’re so iconic, so revered, so entrenched in their own history, that you might think they died long ago. Jasper Johns (born in 1930) is still kicking it, as is Claes Oldenburg (born in 1929). We’ve lost a few of these legends in recent years — James Rosenquist (born in 1933) died in 2017, and Ellsworth Kelly (born in 1923) died in 2015 — and every time we do, the shock isn’t so much that we’ve lost a great, but that they were still around in the first place.

I like the idea of the aged artist, remixing the classics. Earlier this year I saw one half of the Johns two-venue retrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (the other half is at the Whitney). The show definitely played his hits, which are hits for a reason. But it was some of the weirder, smaller-scale, more recent works that stuck with me. The pieces in the exhibition that seemed sprung from Johns’ sketchbook, showing that, even at 91, he’s still an artist, still trying to work it out.

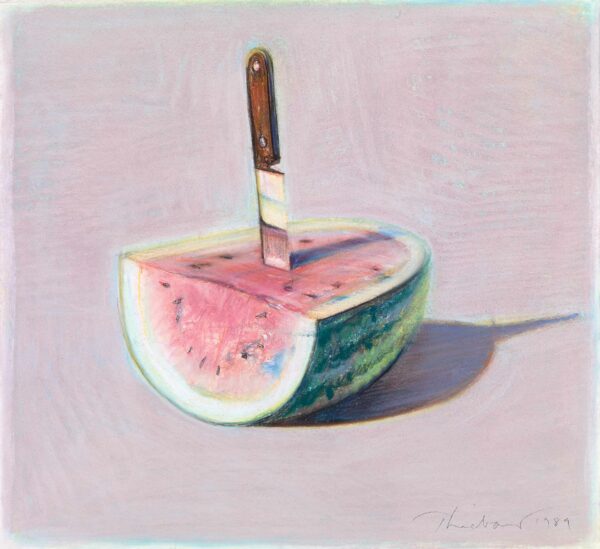

Wayne Thiebaud, Watermelon and Knife, 1989. Pastel on paper, 8 5/8 x 9 7/16 in. Crocker Art Museum, gift of the Artist’s family, 1995.9.30. © 2021 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Thiebaud had it worked out early on. The McNay’s exhibition, which is organized by the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, makes that clear. What’s consistently amazing throughout the show is that it’s hard to see a linear “progression” in his work. While this could be a result of the show’s thematic rather than chronological layout, I think it’s something more: its evidence of how good he truly was. His technique was refined from the start, only to become even more so over the course of his career.

A talent like Thiebaud’s is rare — once or twice in a generation rare. This show radiates through the McNay’s gallery, delivering punch after punch until you’re left on the ropes, gasping for breath. I’m glad I got to see it while Thiebaud was alive, as it has a different air now that he’s dead. What began as a celebration is now a remembrance, and oh what a remembrance it is.

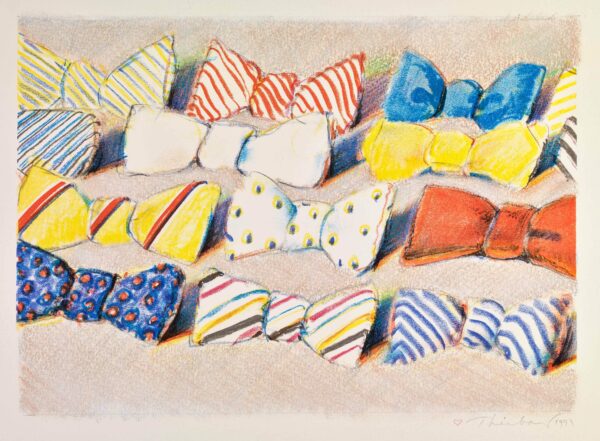

Wayne Thiebaud, Bow Ties, 1993. Color lithograph hand-worked with pastel, 9 7/8 x 13 5/8 in. (image), 15 x19 7/8 in. (sheet). Crocker Art Museum, gift of the Artist’s family, 1995.9.38. © 2021 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

With that, here we go: Wayne Thiebaud may very well be the best painter of the 20th century.

Every now and then, an exhibition comes along that makes you completely reconsider an artist you thought you knew. Oftentimes these shows are organized when an artist is later in their career (or already dead), so themes from their works can be more widely considered and parsed. Although these exhibitions occasionally propel under-recognized talent into the spotlight (see the recent Alice Neel and Hilma af Clint exhibitions), it goes without saying that they’re frequently centered around popular artists — people from the canon who have at least one artwork cited in Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. The paradoxical nature of these art stars, however, is that we tend to only be familiar with them through a textbook; we’ve only ever taken in one or two of their pieces at a time. So when these fateful surveys come around to give you a better picture of famous artists’ careers, it’s a make it or break it moment — you either find out they’re as good as everyone says, or you learn that their work doesn’t stand up.

I’m happy to report, after seeing the survey of his career at the McNay in San Antonio, that Wayne Thiebaud’s work has legs. Like every bright-eyed art history student (or anyone who’s walked through MoMA), I was familiar with his cakes and pies, the impastoed and sensuous works that are simple in subject but flawless in execution.

Wayne Thiebaud, Lipstick and Compact, 1965. Oil on canvas. 11 x 12 in. (27.9 x 30.5 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston. © Wayne Thiebaud / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Paul Hester

My first memory of really realizing Thiebaud’s talent in the wild was when I encountered Lipstick and Compact, an 11 by 12-inch oil painting on canvas in Houston’s Menil Collection. The picture, which depicts its title subjects, is one of the most entrancing (and deceptively simple) works of art I’ve ever seen. Its small scale only made it more so, and its hang, which to my memory was quite high on the museum’s wall, gave it the feeling of a mirror. The lines and shadows of the piece, in Thiebaud’s signature style, contain a multitude of pigment — a kind of wet in wet painting that, when executed correctly, is magical in its tonalities of color.

Thiebaud’s paintings — whether they’re of sunglasses, deli counters or San Francisco cityscapes — have an energy about them that’s immediately palpable and uniquely his. This inherent liveliness is completely antithetical to Thiebaud’s scenes: his city streets are empty, his toiletries sit static on surfaces, and his pastries languish in the fluorescent lighting of refrigerated counters. And yet, somehow, because of his magnificent brushwork (or pastel work or watercolor work), his compositions are alive, churning with kinetic potential.

Wayne Thiebaud, Boston Cremes, 1962. Oil on canvas, 14 x 18 in. Crocker Art Museum Purchase, 1964.22. © 2021 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

While Thiebaud did grow as an artist and become increasingly talented over the years, his paintings from the 1960s are themselves masterworks. Even then, when he was only 40 years old, Thiebaud knew where he was going. Boston Cremes, a moderately sized work from 1962, is the ideal Thiebaud picture. In it, an army of pie slices three pieces wide and five pieces deep stands at attention. The colors within the painting respond to the scene’s light source, accounting for the differing hues that give each slice its own personality. Presentation of the desserts isn’t perfect: slices are angled this way and that, without any clear rhyme or reason. But that’s okay, because this isn’t a patisserie — it’s a soda shop from the all-American Swinging Sixties. Besides being a truly remarkable painting technically, the piece is distinctly of its time. It manages, through nostalgia alone, to conjure images of soda jerks wearing paper hats, rollerskating waitresses, and plush, vinyl-covered booths.

While Thiebaud’s images of food are iconic, perhaps the most striking pieces in the McNay’s exhibition are his portraits. I had never thought of Thiebaud as a painter of people, but it makes sense: if he can capture the personality of a watermelon, what would prevent him from conveying a sitter’s character? Accordingly, his subjects will break your heart.

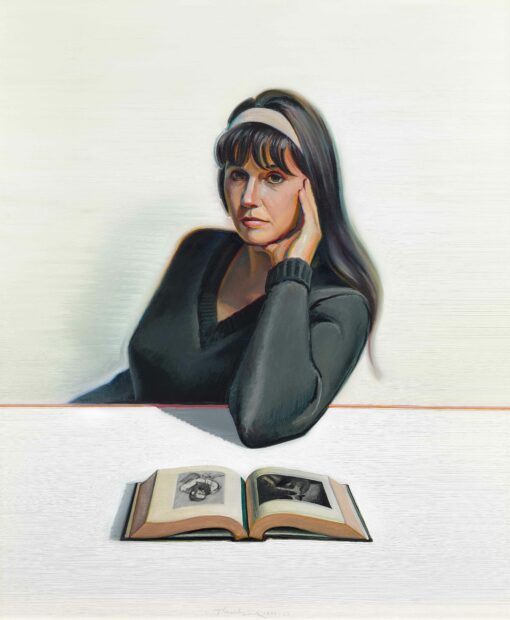

Wayne Thiebaud, Betty Jean Thiebaud and Book, 1965–1969. Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 in. Crocker Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Wayne Thiebaud, 1969.21. © 2021 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

In one portrait from 1965-1969, Thiebaud captures his wife, Betty Jean Thiebaud, looking off while reading a book. Ms. Thiebaud’s stare first appears blank, but it is so much more: it’s contemplative, melancholy, and slightly seductive. The scene is contrived — Ms. Thiebaud’s jet-black hair and V-neck sweater starkly contrast the white table and background. In a sense, you can trick yourself into thinking that the picture is painted in grisaille (grayscale), until you stare into Ms. Thiebaud’s fleshy face. Her character comes through in spite of her surroundings; it comes through because of Thiebaud’s striking use of color. Ms. Thiebaud literally radiates through the space — her shadow, which is denoted by the lightest, most delicate wisps of color behind her, gives her character a depth, as does the fuzzy, out-of-focus look of her far shoulder. The whole scene exudes wistfulness — this is Alex Katz taken to another level.

Just as remarkable is Thiebaud’s Two Seated Figures from 1965, which is in the collection of the Crocker. This large-scale painting is the epitome of marital strife, laid bare. A wall label for the piece lists a quote from Thiebaud, in which he makes sense for us of the odd but charged nature of his portraits:

“Most people in figure paintings have always done something. The figures have been standing, posing, fighting, loving, and what I’m interested in, really, is the figure that is about to do something, or has done something, or is doing nothing.”

Wayne Thiebaud, Two Seated Figures, 1965.Oil on canvas, 60 x 72 in. Courtesy of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation. © Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Sometimes, the simplest and most radical thing to do is to do nothing. Or to find a new way to do nothing. Thiebaud’s work embodies this concept: his pies are doing nothing, in reality — you only think they’re sitting, taunting, looking delicious. His street scenes are doing nothing — it’s your projection that a car, a bus, or a person must be coming around the corner soon, because how could his scene be so empty during the day. His portraits — Thiebaud told you exactly what he thinks about those.

Thiebaud was our 20th century painter of modern life. His pictures exude California, Manifest Destiny, indulgence, and progress. He was a painter of pleasure, a painter of distractions, and a painter of joy. This exhibition was his swan song, and it was a triumph.

Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings is on view at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio through January 16, 2022.

4 comments

That is exactly what Americans think they understand about painting. In terms of art history, however, it works differently from a European point of view. And you can’t convert an emigrated art history into an otherwise empty space. Consumers are not Argonauts!

I have always admired Thiebaud’s work. He was a remarkably skilled handler of paint, and the exhibition at the McNay left me wanting even more. Unfortunately, due to prevailing prejudices against figurative art (on the part of critics, curators, dealers, university professors, etc.), he was generally under-appreciated, if not dismissed altogether as a serious artist (how dare he paint a creamy-looking cake!). I remember so many Whitney Biennials that seemed to purposely exclude the work of anyone who had mastered traditional painting techniques.

Chicano artists have always encountered the same prejudices against representational art. Coincidentally, the late Adan Hernandez was deeply influenced by Thiebaud’s Potrero Hill, a painting he saw at the San Antonio Museum of Art. He was impressed by Thiebaud’s astonishing treatment of perspective, his bold use of color, and by his handling of paint. No painting that Hernandez saw in person had a greater part in the development of his mature style. I discuss Thiebaud’s influence in my forthcoming Glasstire article “Adan Hernandez Paints the Black of Night, Part 2.”

Ruben, I know the SAMA painting you’re talking about, and I almost included it in this piece. It was one of the first street scenes by Thiebaud I ever saw, and it too made me see him and his work in a new way.

Thiebaud’s Potrero Hill and Stella’s Double Scramble were always destinations whenever I visited SAMA.