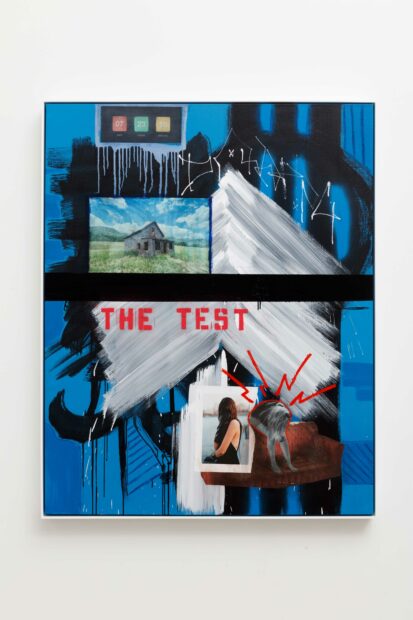

Installation view of William Atkinson: Storm & Shelter at Erin Cluley Gallery. Photo: Kevin Todora, courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

I have to admit, this stuff by William Atkinson pleases my prejudices.

Stirring photos slammed next to reckless paintstrokes, all welded together by implicit grid patterns à la Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Franz Kline — what’s not to like? It’s so bold, so immediate, so, oooooo . . . so unapologetically masculine.

The dude abides. When I met William Atkinson in Dallas at his show at Erin Cluley gallery, Storm and Shelter (continuing through December 23rd), he was refreshingly direct in conversations — a lot like his paintings, which he only allows himself a single night to complete.

His artmaking biography roots itself in this kind of performativeness.

He began his career as a “street artist” in New York and LA, which — I learned in the course of writing this — is different from being a “graffiti artist.” Like other practitioners of his ilk, Atkinson stalked into the night and, working fast to evade onlookers, put captioned pictures (not spray-painted words) onto walls, poles, and city signage. The pieces offered icy (but funny) social commentary on America’s shameless consumerism and other societal ills.

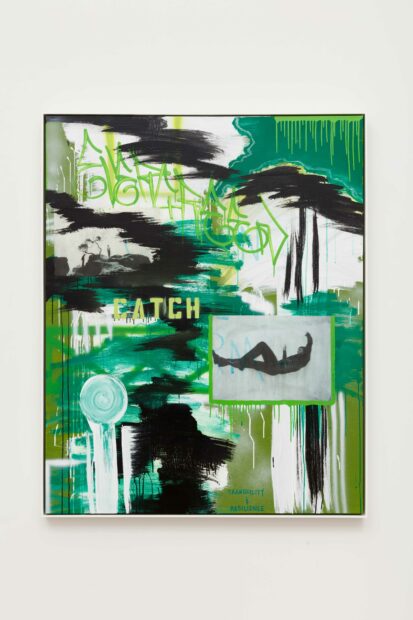

William Atkinson, All You’ve Been Through, 2021, Mixed media on canvas, 60 x 48 in (152.4 x 121.9 cm). Photo: Kevin Todora, courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

“Insurgency” was the flag he flew under from 2009 to 2014. (That word had paradoxical power in those years because Defense Chief Donald Rumsfield prevented military officials from using it to describe the indigenous resistance in Iraq.) Supposedly, Insurgency Inc. was an “art collective,” but it may have been just Atkinson himself (the magician doesn’t reveal his secrets). He crowded into a surprising number of shows in that era and ascended to one little-known hilltop: he was “Sticker Artist of the Year” for a well-known Los Angeles art blog in 2010.

But that’s all in the past (as his work for the military is — that, he won’t talk about), and Atkinson seems archly focused on transcending his former incarnations. Maybe that’s why the Storm and Shelter pieces feel like they’re whipping your retinas around at such high speeds. The man’s running — from something, and toward something, too.

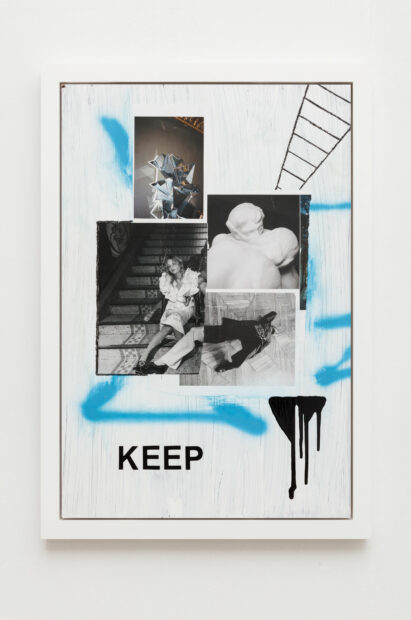

William Atkinson, Fractal Synergy, 2021, Mixed media on board, 36 x 24 in (91.4 x 61 cm). Photo: Kevin Todora, courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

So, he’s transcending.

If we mine the etymology of “transcend,” it comes from “to climb across.” Atkinson’s works seem to show traces of clambering through alleyways and scaling the slop of the street. Like a trekker in urban canyons, these pieces ramble through a variety of perpendicular tensions (wall and road, at least). It isn’t over-explicit, but you also can see how his maelstrom of marks and filched photographs find anchoring in right-angle axes.

Yeah, Atkinson’s still tacking tag-lines and rectangular photos on walls like he did in the old days, but now he dialogs with art history as he goes. This skill has brought his work to galleries in Paris, Madrid, Milan, New York and Miami, and, now (finally!) in his Dallas hometown.

Storm and Shelter has six well-developed 60 x 40 inch paintings and 12 smaller collages — which are in the 36 x 24 inch range. The smaller pieces seem more deeply in thrall to his old street aesthetic, even as they press into fresher visual territory.

Installation view of William Atkinson: Storm & Shelter at Erin Cluley Gallery. Photo: Kevin Todora, courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

Calling to mind Rauschenberg’s 1957 painting Rebus, and the way of seeing promulgated by the recently-dead John Baldessari (1931-2020 — whose graphic sense still colors commercial and fine art everywhere), Atkinson’s small non-canvases are dominated by photomontage. The pictures float on pasty-white Masonite backgrounds which, like his big paintings, are treated with a broad assortment of marks in several mediums. Unlike the paintings, however, these gestures are just accents at play with the imagery — their conversation with the viewer takes a backseat.

Among these marks there’s loaded horizontal paint-strokes with vertical drips, tracery in spraypaint, and — in his three-part, blue-aerosoled set — thin black oil-pastel marks that play games with perspective and planer views. Though they’re poor cousins to the canvases, these dozen smaller works are worthy of more considered examination than I can offer here. I’m even more curious about where Atkinson will take their lines of visual investigation than I am about where he’s going with his big works.

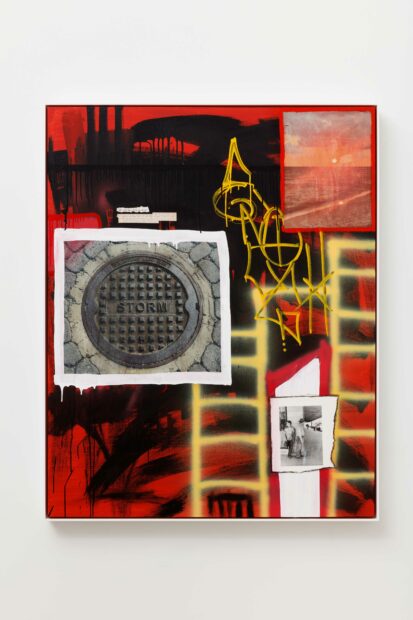

But those big-boned pieces are sexier, so let’s steer toward them. I asked Atkinson in what order he created the canvases, and I almost guessed right: all six were made this year, and Promises to Keep was the first of them. Unified by an overall field of red, the piece leans heavily on black and white.

William Atkinson, Promises to Keep, 2021, Mixed media on canvas, 60 x 48 in (152.4 x 121.9 cm). Photo: Kevin Todora, courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

The rebel flair of this strict, three-tint combo can be found in the flags of communist/anarcho rebel groups — from the Bolsheviks, to the South Sudan Democratic Movement, to the Sandinistas — going back more than a hundred years. It suggests binary thinking and the bloodshed that can come from such points of view.

From the piece’s title, one thinks of the promise of victory nursed in an insurgent’s heart. The impact of the word “storm” on the central image of a manhole cover evokes the chaos of battle. (It’s metal, reminding us of battle shields. Lying prone, it holds the promise of being erected to enable defense). In the painting’s lower right quadrant, one old photo shows two working-class blokes peering ’round a corner. Maybe they’re citizens plotting against the state. (Insurgency again!) In the upper right, we see the circle in vertical — it’s a sunrise or sunset. This may allude to the trope, “dawn of a new age,” or the “sunset” of a toppled regime.

It’s all hotly masculine. Themes of storm (battle, risk, decisiveness, and blood-letting) and shelter (usually through images of the home or women) haunt every work. They’re probably most nakedly displayed in the third painting created in this set: Designed to Hurt.

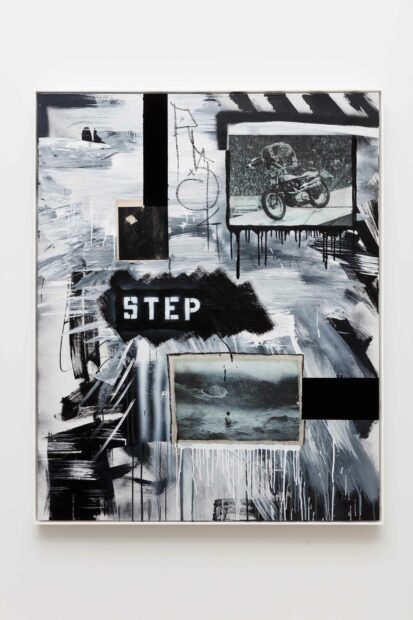

William Atkinson, Designed to Hurt, 2021, Mixed media on canvas, 60 x 48 in (152.4 x 121.9 cm). Photo: Kevin Todora, courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

It’s easy to argue that the visual drama of the black, white, and red trio is closely seconded by the simpler duo of black and white — especially when the artist or designer pushes those blacks and whites to their tonal extremes. In addition to spray paint, Atkinson hits the canvases with oil stick, Krink markers, housepaint, and the acrylic paint called Black 3.0, which is touted as “THE BLACKEST BLACK PAINT IN THE WORLD” by its maker, Culture Hustle (as inspired by a famed dispute with the artist Anish Kapoor — a fetching story you can read about here!). All six paintings make liberal use of that product.

Designed to Hurt seems to have received more of Black 3.0 and all other kinds of paint than its brethren. It gives us lots of facture to follow, even as its overall design — with its aggressive L-shape at center — capitalizes most completely on perpendicularity. Atkinson amps all this right-angle-ness with the two photos he’s bandaged to Hurt. One shows a motorcycler being tossed as his bike touches down on a ramp, and the other shows a dude hip-deep in water backgrounded by a giant sea-swell. The images parade risk even as they cleverly reinforce Atkinson’s bigger conversation with the orthogonal. In this case, we get the hard horizontal of a ramp and the soft vertical of a lurching wave.

Seemingly more a man of action than reflection, one idea Atkinson likes to circle back to is the decision-making framework developed by famed dogfighting strategist, Colonel John Boyd, called the OODA loop: Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. Painstaking in its particulars, this decision-making philosophy has been embraced by institutions and individuals in business, politics, sports, and the military.

In our talks, Atkinson mentioned some of the decisions he’s made in the course of his artistic career. He says his street work was “external” and “anonymous.” In that phase of his art life, his expressiveness was propelled by questions about society as a whole. Coming from the feral urban world into the ordered cosmos of the gallery, his artistic inquiry became self-questioning instead — something that is more consumable in that closed-door intimacy. His efforts became less driven by mysteries pertaining to the tribe, and more propelled by ones pertaining to the individual. It might be said that while most artists in his generation turned toward social critique and the “artivism” we now see everywhere, Atkinson, having “been there, done that,” went another way.

William Atkinson, Trust the Blood, 2021, Mixed media on canvas, 60 x 48 in (152.4 x 121.9 cm). Photo: Kevin Todora, courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

An educator who teaches the Humanities, Atkinson didn’t go to art school. He frankly admits that such an education would enrich his work and, it must be said, the work is young. Atkinson is still clambering through his influences. He hasn’t yet defined a style wholly his own.

But you can’t say the man doesn’t have momentum.

Without education to lean on, he reports that he relies wholly on feeling. He says his wife knows when he’s nearing another all-nighter that’ll make a completed canvas. Emotions are building in him — maybe a word, an image, or some experience has jabbed a sentiment into his chest, and making a picture’s the best way to push it out. This praxis is consistent with that of the best Abstract-Expressionist painters. It’s not surprising he’s invested in himself in an idiom that calls that midcentury style to mind.

Though Pollock’s generation isn’t “modern” anymore, when considering Atkinson, one thinks of that mad fella’s 1951 statement: “Today painters do not have to go to a subject-matter outside themselves. Modern painters work in a different way. They work from within.”

William Atkinson: Storm & Shelter is on view at Erin Cluley Gallery in Dallas through December 23, 2021.