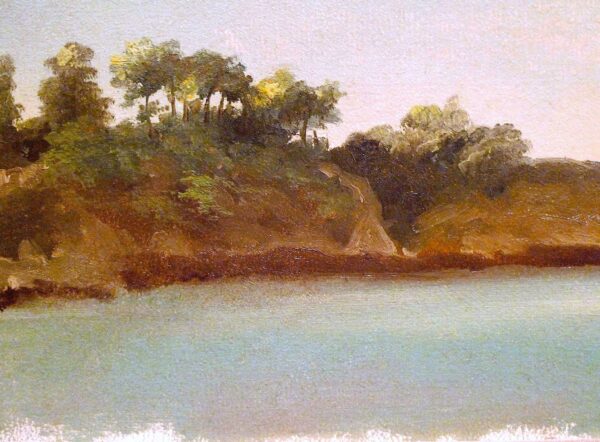

Camille Corot (French, 1796–1875), Waterfall at Terni (cropped at bottom), 1826, oil on paper, laid down on wood, 10 1/2 x 12 1/8 inches, The Whitney Collection, gift of Wheelock Whitney III, and purchase, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, by exchange, 2003. Photo source: Google Arts & Culture. Photos are from the Metropolitan Museum website and publications, unless otherwise noted. Though the overall spatial compression evident in this fresh and beautiful painting, as well as the flickering notations of individual brushstrokes (which seem to dissociate from the motif and float on the surface) in some ways anticipate Impressionism, and even Cézanne, such sketches were regarded as exercises rather than proper art works. Corot more often used these studies for larger, more conventional and highly finished studio paintings than most of the other artists who made plein-air sketches.

Introduction

This article looks at three phases in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s practice of deaccessioning (removing) art from its collection. The rash and secretive sales under director Thomas P. F. Hoving in the early 1970s resulted in scandal, censure, and regulation. During the tenure of Hoving’s successor, Philippe de Montebello, savvy sales and purchases substantially upgraded the collection. I focus on the sale of an unimportant Monet that resulted in the acquisition of two collections with over 200 paintings that dramatically broadened and transformed the museum’s nineteenth-century collection. Finally, I discuss the Met’s recent and very controversial decision — made possible by the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) temporarily relaxed guidelines — to use proceeds from the sale of works for the care of the collection, rather than for new acquisitions. Many fear that the Met’s influential embrace of this practice will prove harmful to other museums.

Deaccessioning Art from Museum Collections

The practice of removing and (usually) selling art from museum collections is referred to as deaccessioning. Deaccessioned works can also be given to or exchanged with other museums or institutions. Though most eminent European museums prohibit deaccessioning, it is utilized by the vast majority of U.S. museums. Museums that deaccession works tend to be less selective in their acceptance of gifts, since they can be sold to acquire more desirable objects.

The “Hoving Affair”

In the early 1970s, reckless and secretive deaccessions by the Metropolitan met with stiff disapprobation, including censure by the College Art Association and condemnation by the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA). Then-director Thomas P. F. Hoving sold or earmarked for sale many important paintings in a rush to accumulate acquisition funds. Hoving reportedly planned to sell hundreds of paintings, including “fourteen routine Monets.” False statements were made about which paintings had been deaccessioned, a word the museum used in a slippery and disingenuous manner. This scandal is how the word “deaccession” entered common parlance in 1972. It had been used in internal Metropolitan Museum documents dating back to the 1940s.

Adelaide Milton de Groot, a donor of 211 paintings, had been tricked into altering a key clause in her will to enable the sale of paintings from her bequest. Moreover, the paintings were sold in a non-public, non-transparent manner that achieved poor results. This raised speculation — as reported by Michael Gross in Rogues Gallery (2009) — that Theodore Rousseau (1912-1974), the Met’s curator-in-chief and vice director under Hoving, might be taking kickbacks.

The Met — which was scrutinized in public hearings initiated by then-state Attorney General Louis J. Lefkowitz — made wholesale changes to its deaccession practices in consultation with Lefkowitz, who represented the public beneficiaries of philanthropy. These changes, which served to make the museum’s transactions more transparent, were summarized by Lawrence Van Gelder in the New York Times (“Metropolitan Will Ease Secrecy On Sales From Art Collections,” June 27, 1973). Lefkowitz, who deemed the new policies to be adequate “safeguards of the public interest,” closed his inquiry into the museum when they were adopted. Hoving declared: “It’s a new era of disclosure.” He added that the new guidelines would “make us the institution that discloses more fully than any I know of.” One should add, however, that this particular new era was not one of Hoving’s choosing.

I give an abbreviated account of the Hoving Affair because it is extremely well documented. It received prominent coverage in the New York Times, which broke the story and followed its every twist and turn. It is treated prominently in two general histories of the Metropolitan: see Calvin Tomkins, Merchants and Masterpieces (1970; rev. ed. 1989) and Michael Gross, Rogues’ Gallery (2009). For an account by a New York Times reporter who played a key role in the exposé, see: John L. Hess, The Grand Acquisitors (1974). For an analysis of the scandal in the context of the history of museum deaccessions, see: Martin Gammon, Deaccessioning and its Discontents: A Critical History (2018).

Most controversially, Hoving sold a Henri Rousseau jungle scene and the prime, plein-air version of Van Gogh’s The Olive Pickers (the latter will be discussed in a review of the Dallas Museum of Art’s Van Gogh exhibition). Both were sold to Marlborough Gallery for the low price of $1,450,000. The Rousseau was soon sold to the Tokyo-based Mitsui & Company for $2 million, and the Van Gogh to Basil Goulandris for $1.5 million. John Canady, who exposed the Met’s sale of these two paintings in the New York Times six months after it had taken place, caught Hoving in a tangle of lies (“Metropolitan Sells Two Modern Masterpieces in an Unusual Move,” September 30, 1972). The late dealer Richard Feigen wrote that he had made an offer on behalf of a client for the Rousseau (the Met informed him that it was not for sale) for a significantly higher price than it garnered from Marlborough (Tales from the Art Crypt, 2000). Feigen added that Mitsui had rebuffed an offer on the Rousseau “in the $75 million range” c. 1990. (Also see Gammon’s extended discussion of the Rousseau painting, which he illustrates in color in Deaccessioning and its Discontents.) Feigen “conservatively” estimated the Van Gogh’s worth at $50 million in Tales From the Art Crypt. Both paintings would be worth more today, which is why it is very bad business for a museum to sell its treasures.

Feigen also notes that Hoving and his colleague Theodore Rousseau misinformed the son of the donor of the Van Gogh that the museum had two other versions of the motif. The Henri Rousseau was a de Groot picture, and Feigen characterizes the museum’s violation of her intent as “most heinous.” Hoving and Rousseau continuously deprecated the quality of the de Groot pictures. Since the expansive American, Nineteenth Century, and Twentieth Century wings had not yet been built at the Met, few of de Groot’s pictures were exhibited in the early 1970s. Because so many of the museum’s pictures were in storage, it was hard to tell which paintings had been sold or traded away.

Tomkins mistakenly says the Henri Rousseau “was one of the few pictures in her [de Groot’s] collection that another museum would have considered good enough to hang” (Merchants and Masterpieces, 1989). The Met, in fact, currently has more than 40 de Groot pictures on display. These include: the museum’s best study of heads by Rubens and an early Jordaens; the museum’s only Van Gogh self-portrait and major works by Delacroix, Lautrec, and Pissarro; important works by American painters including Eakins, Hassam, Homer, and Whistler. Some quality de Groot works that are often exhibited (though presently not on view) include paintings by: Beckmann, Bellows, Jan Breughel, Manet, Matisse, Modigliani, Monet, Morisot, Soutine, and Winterhalter. Even after more than 50 years of very successful collection development after de Groot’s bequest, many of her pictures are still exhibited at the Met. Additionally, she donated works on paper by artists such as Delacroix, Gauguin, Moreau, Moore, Rodin, Roualt, and Seurat that are rarely shown due to conservation requirements. The de Groot collection, in fact, could have served as a good foundation for a small museum.

Initially, it was reported that two de Groot paintings were exchanged with Marlborough Gallery for David Smith’s Becca and Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park #30. But in fact, six de Groot paintings were exchanged: two by Gris, and one each by Bonnard, Modigliani, Picasso, and Renoir. See Hess’s New York Times article of January 14, 1973, which is informative on many points, including how Rousseau got de Groot to alter her will. Due to Hoving’s lies and evasions, press coverage was piecemeal and often partially erroneous, so I recommend Hess’ book The Grand Acquisitors.

In a particularly shadowy deal, 32 de Groot paintings were sold to dealer Harold Diamond in March of 1972 for $80,000 (though these were by all accounts minor paintings, the paltry amount paid for these works, some of which were by big-name artists, sparked suspicion); this money was applied to the purchase of an important Annibale Carracci. Gammon traces the subsequent auction histories of some of the de Groot paintings that the Met sold or exchanged, as well as some of the eleven Impressionist paintings from other sources auctioned in October of 1972 for $489,790. de Groot is also credited as the third donor on the label for Diego Velázquez’s Juan de Pareja, the supreme masterpiece whose purchase in late 1970 for $5,592,000 sparked Hoving’s deaccessioning frenzy.

The Association of Art Museum Directors’ Temporary Guidelines

In order to assist museums during the Covid-19 pandemic, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) temporarily relaxed regulations governing the deaccessioning of art works for a two-year period. Commencing in April of 2020, museums are permitted to use proceeds from sales for “the direct care of the museum’s collection.” This change resulted in controversies, as reported by the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Baltimore magazine, ARTnews, Glasstire, and Hyperallergic. The Metropolitan reserved the right to sell art works under these relaxed guidelines. In September of 2021, the auction house Christie’s announced that it was selling works from the Met’s collection and that the proceeds from the sales would go to the care of collections rather than acquisitions. The last section of this article examines this decision and its implications for the museum world in the U.S.

The Development of the Met’s European Paintings Collection Since 1980

Deaccessioning is usually a process of “trading up,” wherein museums sell multiple lesser works to acquire a much more expensive one, sometimes supplemented by endowments earmarked for acquisitions. The Met has been winnowing and refining its collections since 1885. Between the 1980 summary catalogue of European paintings and that of 1995, it acquired 135 paintings and deaccessioned 199. Since March 1995, it has acquired and retained a staggering 515 paintings by European artists born before 1865 — this is not counting the 19 paintings published in the 1995 catalogue as anticipated gifts that were formally accessioned at a later date.

I cannot account for additional paintings if they were both accessioned and deaccessioned between the publication dates of the two summary catalogues (1980 and 1995), since they would not show up in the second catalogue. Likewise, any paintings both accessioned and deaccessioned after the second catalogue would not show up on the website. Additionally, I cannot trace any paintings accepted as gifts and subsequently sold without ever being accessioned (i.e. officially registered as part of the collection). The Met’s annual report for the year 1987-88, for instance, notes that 29 “nonaccessioned European paintings were sold at public auction for net proceeds totaling $1,480,824.”

The 1995 catalogue listed 2,500 European paintings, whereas the website currently lists 2,625. Consequently the net gain has been a little over 120 paintings since 1995 and only about 60 since 1980. Without the 220 pictures from the two collections discussed below, the net size of the collection would have diminished rather than increased.

Swap Sweepstakes: Middling Monet Nets Met Plein-Air Bonanza

In one astonishing exchange, the sale of a single, relatively unimportant painting — in conjunction with the construction of purpose-built small-scale galleries — initiated a process that reaped the almost unimaginable bonanza of 220 European paintings from two collectors, most of which were plein-air sketches. This resulted in the Met possessing the best and most comprehensive collection of Romantic-era landscape oil sketches and paintings in the U.S. Philippe de Montebello, then-director of the Metropolitan, said the acquisition of the Wheelock Whitney collection “added a new dimension to our early nineteenth century holdings” (Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Fall 2003).

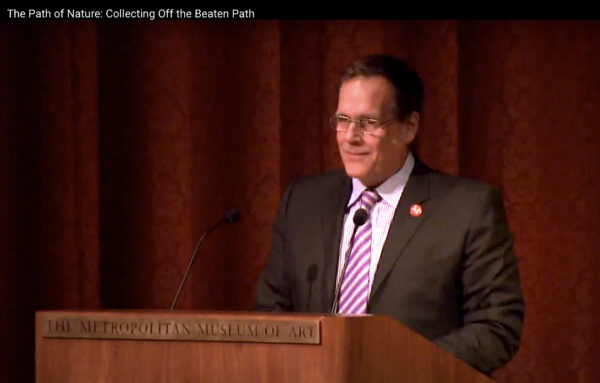

Wheelock Whitney lecturing on his collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 10, 2013. Photo source: screen grab from the video The Path of Nature: Collecting Off the Beaten Path (2013).

Gary Tinterow, now the Director and the Margaret Alkek Williams Chair of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, was the curator who negotiated the new acquisitions and oversaw their installation at the Metropolitan. In 2009, Tinterow, who was then the Engelhard Curator in Charge of the Department of Nineteenth-Century, Modern, and Contemporary Art at the Met, explained that when the Met decided to purchase a half-interest in the Whitney collection, “Eugene V. Thaw felt encouraged to consider the Metropolitan a fitting home for this much larger collection of landscape oil sketches, which we will share with the Morgan Library” (James R. Houghton, ed., Philippe de Montebello and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1977-2008, 2009). In the same publication, written when most of the Thaw collection had entered the Met, Tinterow said the museum’s holdings of this material was equaled only by the Kunstmuseum in Winterthur and the Musée Granet in Aix.

Eugene Thaw with Colin Bailey, Director of the Morgan Library and Museum. Photo source: © The Morgan Library & Museum, photography by Graham S. Haber.

Most scholars believe plein-air sketches were not intended to be seen by the general public. The degree to which this manner of sketching was practiced, as well as the existence of most of these paintings, was unknown until the second half of the twentieth century. These sketches were made out-of-doors — usually very rapidly on paper or on small panels — as exercises in rendering landscapes and the effects of light. Sometimes these studies would be mined for background elements in larger, formal works executed entirely in the studio. In a 1978 article, the curator Philip Conisbee argued that, in addition, these sketches expressed a “tender and loving regard for the world,” and also provided city dwellers with “the respite of enveloping nature.” These works were made in the context of Romanticism and Neo-classicism, and were generally not deemed proper art works for exhibition by art collectors, museums, or other institutions.

Even Corot, the best-known practitioner of plein-air painting, was trained in a Neo-classical ethos. As was the general practice by other artists who made these kinds of sketches, he never sold or exhibited any of them, though he sometimes rented or gifted them to other artists. Plein-air sketches can be compared to the clay models sculptors like Bernini made as preparatory works for marble sculptures: though essential for the creation of their art, they were regarded as tools rather than proper art objects. See my Glasstire article, “Apollo and Daphne: A Tale of Cupid’s Revenge Told by Ovid and Bernini.” For an overview of the plein-air sketch written in connection with the exhibition True to Nature, see Sarah E. Fensom, “Painting al Fresco,” in Art and Antiques (2020).

This section explores the Whitney and Thaw collections (supplemented by other gifts and purchases), and it examines the vogue for collecting these sketches in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries in the context of the Metropolitan’s collection.

Acquisition of the Wheelock “Lock” Whitney III Collection, 2003

In this singular instance, a relatively valuable work (in monetary terms) was sold to acquire a collection of many works of lesser monetary value that, taken together, were of far greater aesthetic and educational value.

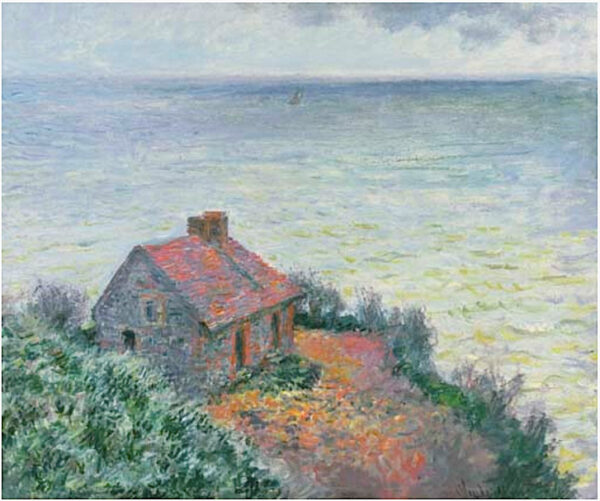

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Cabin of the Customs Watch, 1882, oil on canvas, 23 x 27 ½ inches, (59.188.2) sold by the Metropolitan Museum in 2003. Photo source: Christie’s.

On May 6, 2003, the Metropolitan sold Cabin of the Customs Watch (1882) by Claude Monet at Christie’s for $1,799,500. This rarely exhibited painting was one of three iterations of this motif owned by the Met that were published in the museum’s 1995 catalogue. Monet painted fourteen in 1882, and none represent his best work. It was rightly deemed superfluous to the Met’s world-class collection of Monet paintings. The museum, which has sold a number of Monet paintings over the years (including one of the other versions of Cabin of the Customs Watch), currently owns 42 Monets.

In 2003, the museum used proceeds from the Monet to purchase a half-interest in 56 paintings assembled between 1972 and 2000 by the art historian, gallerist, and collector Wheelock Whitney III (b. 1949), who is from a Minnesota branch of the Whitney family. The collection is credited as a combination promised gift from Whitney, and as a purchase by exchange from Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, who had donated the Monet to the Metropolitan in 1959.

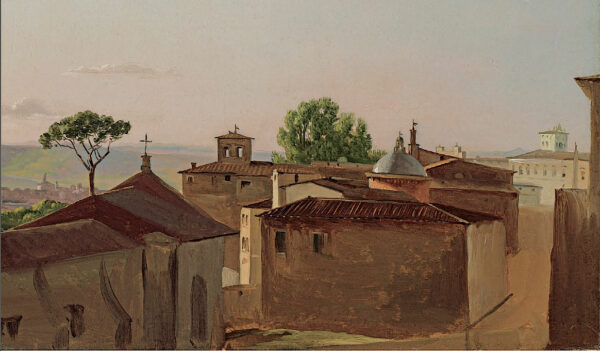

Charles Rémond (French, 1795–1875), View of the Basilica of Constantine from the Palatine, Rome, c. 1822–25, oil on paper, laid down on canvas, 12 3/4 x 10 5/8 inches. The Whitney Collection, promised gift of Wheelock Whitney III, and purchase, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, by exchange, 2003. Executed rapidly on paper before the motif, this painting has an unusually authoritative quality for a picture of this size.

Whitney received a B.A. in art history from Yale in 1973 and an M.A. from the Courtauld in 1975. He was an early collector and scholar of plein-air painting. The artists he eventually collected were so obscure that Whitney himself was only familiar with two of them (Camille Corot and Louis Léopold Boilly) when he bought his first painting, an offbeat Corot of a black cow in a barn. Whitney published articles on Pierre Henri de Valenciennes and Géricault in Burlington Magazine, (1976; 1978), and he also authored Géricault in Italy (1997).

In 1970 Whitney took a year off from Yale and worked for the eminent dealer Jack Baer — whom he credits with teaching him how to look at art — at the Hazlitt Gallery in London. He returned to Baer’s employ after completing his B.A. He recalls that it was a most propitious time, when art dealers had begun presenting the work of forgotten artists on the international market, including plein-air sketches. Whitney organized several important exhibitions at the renamed Hazlitt, Gooden & Fox gallery, including The Lure of Rome (1979), which treated plein-air paintings by Northern artists. He frequented auction houses during his lunch break, where he found little competition for the paintings he coveted. Whitney also made numerous trips to Paris to purchase paintings. In 1989, he moved to New York and opened a commercial gallery called Wheelock Whitney and Company on East 62nd Street.

Léopold Robert (Swiss, 1794–1835), Brigand and His Wife in Prayer (detail), 1824, oil on canvas, 17 5/8 x 14 3/8 inches. The Whitney Collection, promised gift of Wheelock Whitney III, and purchase, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, by exchange, 2003.

Whitney promised his half-share in 56 paintings to the Met in 2003. This collection ranges in date from the late eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century. It features an assortment of subjects: landscapes, architectural ruins, genre paintings — including depictions of monks and brigands — and even a pair of academic nude studies. My favorite among the genre paintings (illustrated above) depicts a bandit and his pregnant wife praying before a shrine, with a beautiful and atmospheric mountain background.

Despite its diversity, Whitney does not regard his collection as a random agglomeration. He calls collecting “the great, enduring passion of my life.” Moreover, he recalls “in near Proustian detail the circumstances under which I bought each of my paintings, and the thoughts and feelings that surrounded the acquisitions… There was nothing casual about my pursuit of any of these objects.” Unless otherwise noted, all Whitney quotes are from his 2013 lecture “The Path of Nature: Collecting Off the Beaten Path,” which was given in conjunction with the exhibition of his collection at the Metropolitan.

About two-thirds of the Whitney paintings are plein-air sketches or more finished, small-scale landscapes. The majority of them are by French and Belgian artists, though five are by Swiss or German painters. Most were painted in Italy. When Whitney collected these paintings, seven had uncertain or incorrect attributions and have since been reattributed. Some were slow to disclose their paternity. Whitney bought a painting fragment from an eccentric Scottish lord for £100 in 1977, but did not learn who painted it until he came across Louis-Stanislas Marin-Lavigne’s lithograph of the painting in 2005. Commissioned by King Louis Philippe from the French artist Auguste-Hyacinthe Debay, the painting was damaged in 1848, when the Palais-Royal was sacked.

Some Whitney paintings remain unattributed, including The Arch of Titus, which is one of the collector’s favorites. An issue of the Metropolitan Bulletin, The Path of Nature: French Paintings from the Wheelock Whitney Collection, 1785–1850 (2013) by Research Curator Asher Ethan Miller (Whitney’s research assistant on the Géricault book), serves as the collection’s catalogue and can be downloaded here.

Eugene and Clare Thaw in Santa Fe, New Mexico, c. 1990. Photo source: The Clark Art Institute. In a 2002 article cited below, Eugene Thaw told Jason Edward Kaufman of the New York Times: “As a collector, I feel my legacy will be to bring the things my wife and I have collected and enjoyed into the public domain. Whereas some collectors feel their ultimate achievement would be a record-breaking sale at Sotheby’s, I believe one can ask for a higher meaning than that.”

The Eugene V. Thaw Collection and the Henry Heinz II Galleries

The eminent dealer, collector, and philanthropist Eugene V. Thaw (1927-2018) assembled and donated multiple collections. In a 2018 article in Architectural Digest, Steven A. L. Aronson recalls that Thaw estimated the worth of his benefactions within the state of New York in the vicinity of a billion dollars. Named after the socialist organizer and politician Eugene V. Debs, who died the month he was born, Thaw had studied with Meyer Schapiro and Millard Meiss at Columbia University, but did not complete a graduate degree. He perceived that money and social status were necessary to excel in both the academic and museum worlds at that time. He wanted to work directly with art, so he became a dealer. Thaw opened the New Book Store and Gallery in 1950, and from this humble start he rose to become one of the most admired and public-minded dealers in the U.S. See Thaw’s interview with James McElhinney for the Archives of American Art (AAA) taped on October 1, 2007.

We can contrast Thaw with his nemesis, the afore-mentioned Theodore Rousseau, who lacked Thaw’s eye and reverence for scholarship, but was born with the wealth and social connections that Thaw did not possess. Rousseau also had dodgy ethics. As an operations officer with the Office of Strategic Services (the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency) he worked to recover art looted by the Nazis during World War II. But in 1948, when Rousseau was already a curator at the Metropolitan, he told the New Yorker that U.S. museums should keep art from Germany, including what “Nazi bigwigs got, often through forced sales” (i.e. looted art). In the 1960s Rousseau associated with Bruno Lohse, a Nazi dealer who was Hermann Göring’s art looter, while Lohse was selling (potentially looted) art in New York. Rousseau also met with Lohse in several European cities. Rousseau was the person who tricked de Groot into changing her will, and he was at the center of the Met’s deaccession scandal in the early 1970s that is discussed above. See Rousseau’s obituary in the New York Times and his entry in the Dictionary of Art Historians.

Thaw notes in the 2007 AAA interview that he had a bad relationship with the Met during Rousseau’s lifetime, because he “was such a snob” and “was everything I was against.” In the interview Thaw also details Rousseau’s “come-uppance” over a Delacroix that he had tried to sell to the Metropolitan. Thaw gives a more detailed account of the Delacroix episode in an illustrated 2008 Aronson interview in Architectural Digest that is largely devoted to Rousseau’s snobbery. Thaw also relates how Rousseau incorrectly questioned the attribution of a Giambattista Tiepolo painting that he had sold to Charles and Jayne Wrightsman, who were the Met’s greatest patrons of European paintings during the last half-century.

Thaw — who was then the director of the ADAA — was one of the whistle blowers who alerted the New York Times to what would become the Metropolitan’s deaccession scandal known as the Hoving affair.

Thaw was a passionate collector. His Native American collection had its origin when he visited Santa Fe to appraise the O’Keefe estate in 1986. He built a house, bought a ranch, and ultimately collected over 1,000 objects, which went to the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y., because it was the only museum willing to exhibit the collection in its entirety. Ralph T. Coe (1929-2010), a notable scholar and collector of Native American art who gave his choice objects to the Metropolitan, calls it the best private collection of Native American art formed in this generation. Thaw told Aronson in a 2008 Architectural Digest interview that Native American art was equal to that of any other culture: “this collection reflects my aesthetic sensibility as surely as any of my others. Because what I ultimately discovered was that American Indian could hold its own with any art anywhere — it could stand alongside Asian, African, Egyptian, European and Maori masterpieces.”

Thaw’s next collection consisted of over 200 metal ornaments from the Eastern Eurasian Steppes, which he gave to the Met in 2002. Thaw referred to it in his AAA interview as the best collection in the world of this material. It was the subject of a Met exhibition in 2002-2003.

Thaw transitioned to collecting material he called “Dark Ages barbarian jewels… Merovingian, Lombardic, Ostrogothic, Gothic and Hunnish,” in another Architectural Digest interview with Aronson. They were given to the Morgan Library in 2012 for a new treasury room. The Morgan press office informs me that this collection totals 113 objects.

Thaw’s most valuable collection was that of old master and nineteenth century drawings. Thaw was connected to the Morgan from the 1960s, and his drawings were first exhibited at the museum in 1975, when he made the collection a promised gift. Thaw chose the Morgan because of its high scholarly standards. In a 2015 interview by Alain Alkann, Morgan director Colin Bailey said it is “one of the most remarkable collections of Old Master drawings and nineteenth-century drawings ever assembled.” Thaw referred to the 420 drawings as his “life’s work.” The collection was periodically exhibited at the Morgan and donated in stages. His collection of plein-air paintings owes its dramatic growth to a 1994 Morgan exhibition of his drawings. It left many empty nails on Thaw’s walls, which he filled with plein-air sketches. It quickly became one of the best collections of plein-air paintings ever assembled by one person.

In a 2002 New York Times article, Jason Edward Kaufman noted that Thaw had about 100 plein-air paintings, intended for the Morgan and the Metropolitan. In the 2007 AAA interview Thaw said he owned about 120 plein-air sketches, but he makes no mention of the Met as a possible destination for them.

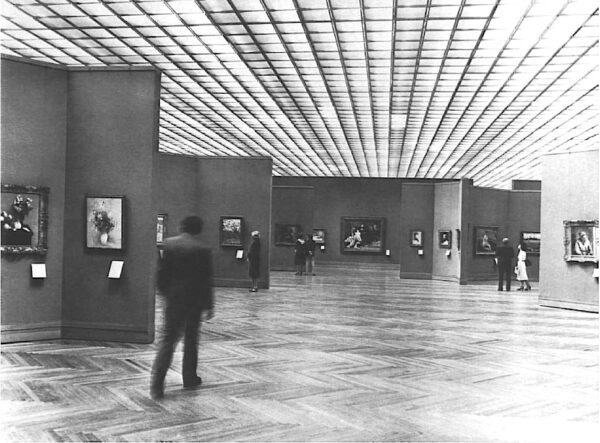

The Met’s open-plan, modernist André Meyer Galleries for nineteenth century art, which displayed many paintings that had long languished in storage, opened to great acclaim in 1980. Nonetheless, a comprehensive redesign of the galleries, which Glen Collins in the New York Times called “the most ambitious internal renovation” in the museum’s history, began in 1989. It was undertaken when the museum was in competition with other major museums for the Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg collection, a premiere collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. Promised to the museum in 1991, the Annenberg paintings were the most important gift of nineteenth century paintings to the Met since the H. O. Havemeyer collection in 1929. Its acquisition filled crucial gaps in the collection and it dramatically underscored the need for galleries that could show far more pictures than the André Meyer Galleries. Beaux-Arts style galleries — conceived in the spirit of the 1890s — with columns, bays, baseboards, wainscoting, and cornices, were designed by Tinterow and Senior Exhibition Designer David Harvey. They opened in 1993. See Tinterow’s publication, The New Nineteen-Century European Paintings and Sculpture Galleries (1993), which can be downloaded here.

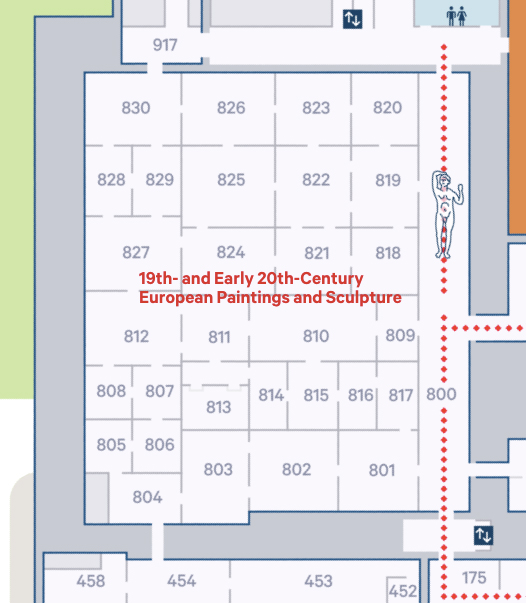

Plan of 19th and Early 20th Century Galleries, second floor, Metropolitan Museum. The Heinz galleries are: 804 (European Vision of North Africa; 805 (The Rise of Plein-Air Sketching and Landscape Painting about 1800); 806 (Northern European Painters in Italy); 807 (Northern European Landscape Painting); 808 (Nineteenth-Century British Painting); 812 (Courbet); 827 (Salon Painting); 828 (Bonnard, Vuillard); 829 (Fin de Siècle Avant-Garde); 830 (Early Matisse and Picasso).

Initially, the Meyer galleries had offered a vista to the Michael Rockefeller Wing of what was then called “primitive” art on the floor below. Due to Nelson Rockefeller’s objection, a wall was erected to block that view. In December of 2007, the Metropolitan Museum opened its expanded and reconfigured nineteenth century galleries that utilized the 8,000 square feet of formerly empty space above the Oceanic gallery in the Rockefeller wing.

These galleries were conjured out of thin air, in an even more dramatic recuperation of space than the several exhibition spaces that Montebello carved out of storage space, such as the Byzantine “crypt” beneath the great staircase that now displays Coptic art.

Named the Henry Heinz II galleries, these new galleries are situated on an east-west axis on the south side of the building, numbered from 804 to 830 in the map above. The paintings discussed in this article are concentrated in rooms 805-807, with others on view in 803 (Corot), 804 (North Africa), and 808 (British).

Eugène Isabey (French, 1803–1886), A Storm off the Normandy Coast (cropped on top and sides), probably 1850s, oil on paper, laid down on canvas, 13 x 20 inches, gift of The Eugene Victor Thaw Art Foundation, 2007. Despite its compelling, sketch-like qualities, this work could not have been painted on the scene, in a violent storm, even if the artist had been tied to a mast like Odysseus, or situated on a high promontory, where visibility would have been nil.

When Thaw saw the Whitney paintings (and a few of his own) installed in the intimate galleries that had been created for them, he appreciated the space’s suitability for his plein-air paintings. Carol Vogel noted in 2009 that Thaw had originally thought of donating them to the Morgan, but upon seeing the new galleries, “they fit so well there that we started talking.” Oil paint — unlike charcoal, pencil, pen, gouache, or watercolor — protects paper. Consequently, oil-based plein-air sketches — even when they are executed on paper — can be exhibited on a long-term basis. Therefore the Met’s new galleries provided the opportunity for portions of Thaw’s collection to be on continuous display.

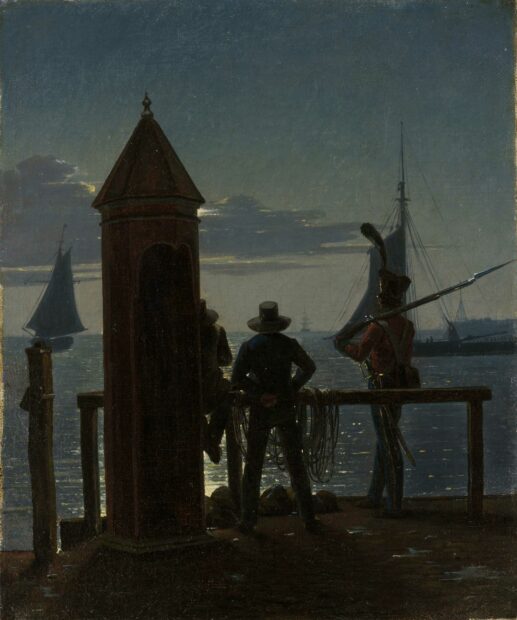

Martinus Rørbye (Danish, 1803–1848), View from the Citadel Ramparts in Copenhagen by Moonlight, 1839, oil on canvas, 11 3/8 x 9 5/8 inches, gift of Eugene V. Thaw, 2007.

Thaw gave seven paintings to the Met in 2007 before the Heinz galleries opened, and he contributed to the purchase of another one. Most of these works were not plein-air sketches, and six were painted on canvas. Seven were by German or Danish artists, including two by Carel Gustave Carus, who studied with Caspar David Friedrich. The Rørbye illustrated above and a Johan Christian Dahl perfectly complement the museum’s Friedrich, which is also a nocturnal scene of figures in a landscape seen from behind. The Met was the first U.S. museum to have a gallery (807) focusing on Friedrich and his students, followers, and northern contemporaries. Thaw’s 2007 gifts enabled the Met to make this claim. I discuss this important Friedrich in my Glasstire article “Oil Begets Oil: Wrightsman Gifts to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of European Paintings.”

Carl Rottmann (German, 1797–1850), The Cemetery at Pronoia near Nauplia (cropped on all sides), c. 1841-47, oil on canvas, 10 x 12 inches, gift of Eugene V. Thaw, 2007. This painting commemorates Bavarian soldiers who died fighting for Greek independence. One couldn’t possibly have chosen a more Romantic and Byronic subject.

In 2009 Thaw gave 123 oil sketches jointly to the Morgan Library — which does not have a permanent space devoted to paintings, apart from those in J. P. Morgan’s former office — and to the Metropolitan. (See accession numbers 2009.400.1-123, here and here.) Whitney, in turn, donated a landscape by the Danish artist Fritz Petzholdt to the Met in Thaw’s honor, also in 2009.

In 2016 Thaw gave 19 more paintings jointly to the Morgan and the Met. (See accession numbers 2016.758, and 2016.802.1-18 here.) In 2018 the Met received six paintings (including a small Canaletto, a portrait of a girl by Degas, and a Salomé by Moreau), as well as six more plein-air sketches jointly gifted to the Met and the Morgan. These six non-plein-air paintings, along with a final picture by Boilly given in 2019, came to the Met through the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust. See accession numbers 2018.289.1-6, 2018.830.1-6, and 2019.21 here.

John and Charlotte Gere: Pioneers of Plein-Air Collecting

Before focusing on other aspects of the Met’s collection, I want to briefly examine the pioneering collectors John and Charlotte Gere. Best known as a curator of Italian drawings at the British Museum, John Gere (1921-1995) bought his first plein-air sketch around 1950. Having seen the sketches by the Welshman Thomas Jones — rediscovered in 1954, when they sold at Christie’s for twenty guineas (a guinea is one pound and five pence) or less — he located another Jones sketch and bought it for the British Museum. He also saw a reference to sketches by Pierre Henri de Valenciennes, which Princess Louis de Croÿ had donated to the Louvre in 1930. Gere went to Paris and studied them. On this very limited basis, Gere made a perceptive hypothesis: “it may well have been common practice in Rome at that period to make sketches of this kind” (British Museum Quarterly, 1959).

Charlotte Gere wrote that John recognized the uniqueness of these sketches, and he decided “the best way to study them was to collect them” (A Brush with Nature: the Gere Collection of Landscape Oil Sketches, 1999). John bought a Thomas Jones around 1955, and Charlotte identified another one in a shop in 1957, only a few weeks after they had met, which John purchased for five pounds. As sixteenth century Italian drawings (hitherto available for a few pounds) and Pre-Raphaelite drawings (Burne-Jones drawings could be had in bundles for less than a pound each) rose in price, John turned his personal collecting energies to plein-air paintings.

Charlotte Gere recalls that there was no established market in this period of “uncharted waters.” Oil sketches were uncatalogued, often unattributed, and rarely on view in museums —which sometimes refused requests to view the collections they did possess. Charlotte stumbled upon a room of sketches in Frankfurt, but was never allowed to look at them properly or ascertain any information about them. She notes that the former curator of the Musée Granet in Aix refused requests to view its large body of sketches by its namesake artist François Marius Granet and that of Jean-Antoine Constantin (the latter were acquired out of pity for the artist’s widow and at one time were earmarked for disposal). The sketch Thaw donated jointly to the Met and the Morgan is a great rarity — a plein-air sketch signed by Granet that is not in the Musée Granet. Due to the difficulty of studying this material, Charlotte points out that a private collection of representative examples “became a form of scholastic tool as much as an aesthetic experience.”

Charlotte says the exhibitions of Italian sketches at Hazlitt, Gooden, and Fox in 1978 and 1979 helped to render the material more available, as well as more expensive. She notes in her essay that plein-air sketches have sold for more than £50,000, and are poised to reach six figures. They are thus “highly prized and equally highly priced.” The exemplary Gere collection of more than 80 plein-air sketches went on long-term loan to London’s National Gallery in 1999. I saw this exhibition and I hoped some U.S. museums would also open dedicated spaces to plein-air sketches, but I was in no way prepared for what the Met has achieved.

Denis, Valenciennes, and Michallon at the Metropolitan

Installation shot with view of gallery 806 facing into gallery 805 (where paintings by Denis, Valenciennes, and Michallon are hung). Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova

Of the works in the two Hazlitt, Gooden, and Fox exhibitions noted above, Charlotte Gere singles out Simon Denis’ A Torrent at Tivoli, a luminous study of running water, foam, and rocks, c. 1789-93, which she and John purchased in 1978. It was the first signed sketch to surface by a mysterious but extremely talented artist. Wheelock Whitney — who regrets not purchasing it — refers to the painting as “the one that got away.”

Simon Denis (Flemish, 1755–1813), View on the Quirinal Hill, Rome (cropped at left and top), 1900, oil on paper, laid down on canvas, 11 5/8 x 16 1/8 inches, The Whitney Collection, Gift of Wheelock Whitney III, and Purchase, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, by exchange, 2003.

View on the Quirinal Hill was the second signed plein-air sketch by Denis to surface on the art market, and this time Whitney did not hesitate to purchase it. It is his favorite painting, and within the corpus of plein-air sketches, Whitney considers it second only to the Valenciennes sketches in the Louvre. It is in the center of the installation shot pictured above.

Miller, in a 2013 entry on the Met’s website, writes that this painting benefits from both “the investigatory properties of a sketch and the more highly developed features of a finished picture.” It is a private exercise that lacks “technical finish and a clear adherence either to the Picturesque or the Sublime,” and thus “it did not meet the criteria for a complete work of art according to the standards of the day.”

Whitney bought a group of four other Denis sketches (two landscapes and two cloud studies) that were probably sourced from the Paris flea market. They were offered to him via Polaroid snapshots in the late 1980s. Thereafter prices for prime Denis sketches were prohibitive, though Whitney managed to obtain two more by attribution rather than acquisition.

Simon Denis (Flemish, 1755–1813), Fortified Wall, Italy, c. 1786–1806, oil on paper, laid down on wood, 13 1/8 x 15 7/8 inches, The Whitney Collection, gift of Wheelock Whitney III, and purchase, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, by exchange, 2003.

In the 1990s, when Whitney installed his collection in a new apartment, the signed Denis sketches were placed in close proximity to Fortified Wall. Recognizing the similarities, Whitney realized that it, too, was a Denis. He had bought it at Christie’s in London in 1976, where it was misattributed to Valenciennes. As the first Denis sketch to enter a contemporary art collection, Whitney calls it “the first Deny oil sketch to enter captivity.”

After living with View from the Villa d’Este, Tivoli (acquired in 1978) for twenty years, Whitney says “one day something clicked… and I realized that it was another work by Simon Denis.” The painting’s color and brushwork led Whitney to make this identification. The Met website lists it as attributed to Denis.

Simon Denis (Flemish, 1755–1813), Sunset, Rome, c. 1789-1806, oil on paper, 8 1/4 x 10 3/8 inches, Thaw Collection, jointly owned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Eugene V. Thaw, 2009.

While Whitney’s early purchases helped to bring Denis out of the shadows of art history, Thaw’s five Denis sketches were acquired between 1998 and 2005, by which time the artist’s plein-air paintings had become highly collectible. Sunset, Rome sold at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris for 820 French fancs in 1977. In 1996, it sold again at the Hôtel Drouot, this time for 270,000 Fr ($51,649). Hazlitt, Gooden & Fox sold it to Thaw in 1998.

Whitney calls this sunset “spectacular.” Miller sees it as an “evocation of the Sublime,” and compares the waterspout cloud to a volcanic eruption.

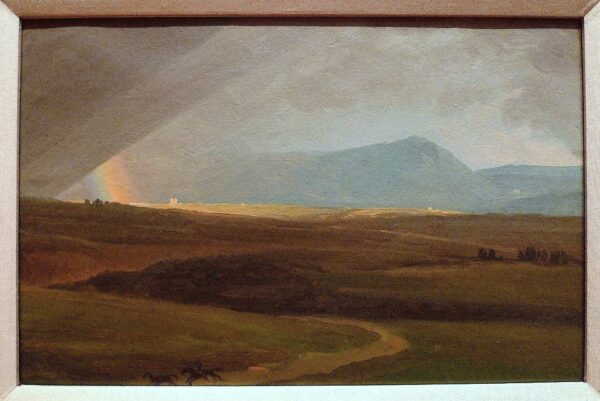

Simon Denis (Flemish, 1755–1813), Landscape near Rome during a Storm, c. 1786–1806, oil on paper, 9 1/4 x 14 1/8 inches, Thaw Collection, jointly owned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Eugene V. Thaw, 2009. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

This fresh and astonishing display of lighting effects depicts changing cloud formations. It is, of course, impractical to paint on paper in a rainstorm. This painting was based on a drawing, as noted by an inscription on the back, which indicates that the rainbow is visible where the sun shines, and is crossed by rain where the shadow begins. The inscription says the drawing was made near Rome.

The Met has the best museum collection of Denis’ plein-air sketches. The Louvre, which is so rich in paintings by Valenciennes (131), Corot (129), and Achille-Etna Michallon (33), has but three paintings by Denis, only one of which is a sketch (purchased in 2005).

Valenciennes is represented in the Met’s collection by three undoubted paintings (one given by Whitney and two given by Thaw jointly to the Morgan and the Met), as well as nine much-debated paintings given to the Met and the Morgan by Thaw that are currently listed as by Valenciennes or his circle.

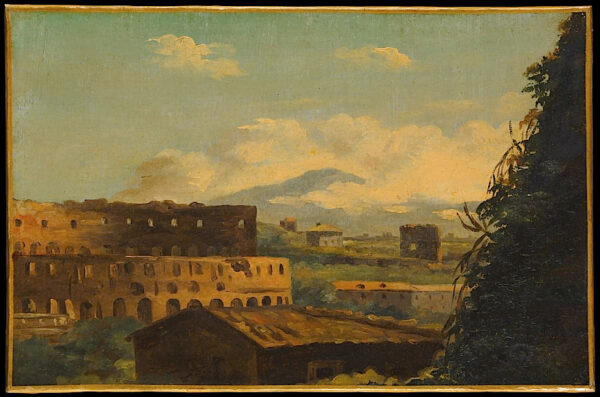

Pierre Henri de Valenciennes (French, 1750–1819), View of the Colosseum, Rome, oil on board, 10 1/4 x 15 3/8 inches, Thaw Collection, jointly owned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Eugene V. Thaw, 2009.

In the painting illustrated above, Valenciennes boldly cropped the Colosseum on the left and depicted a truncated pyramid that is overgrown with vegetation on the right. This is one of several instances in which Valenciennes made a replica of one of his plein-air sketches. The other version of this painting is in the Louvre, which owns most of the artist’s work. As William M. Griswold notes, the Thaw painting is “arguably freer and more boldly conceived” (The Thaw Collection: Master Drawings and Oil Sketches, Acquisitions Since 1994, 2002). Paula Rea Radisich says the practice of painting replicas of sketches “was apparently a common one in the 18th century.” She also believes that Valenciennes and other artists might even have shown plein-air sketches in exhibitions, including the Paris Salon (“Eighteenth-Century ‘Plein-air’ Painting and the Sketches of Pierre Henri de Valenciennes,” Art Bulletin, 1982).

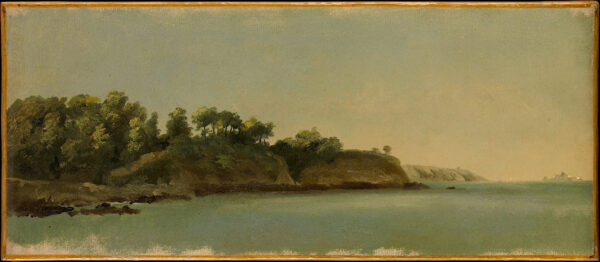

Pierre Henri de Valenciennes (French, 1750–1819), The Banks of the Rance, Brittany, possibly 1785, oil on paper, laid down on canvas, 8 3/8 x 19 3/8 inches, The Whitney Collection, gift of Wheelock Whitney III, and purchase, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, by exchange, 2003.

This is one of 26 studies by Valenciennes that were discovered in 1973. The artist is thought to have visited Brittany in 1785, which is a possible date for this work.

Pierre Henri de Valenciennes (French, 1750–1819), The Banks of the Rance, Brittany (detail), possibly 1785. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

In his treatise on landscape painting published in 1800, Valenciennes recommended making quick studies after nature, an approach that is evident in this painting. Valenciennes mounted his sketches on cardboard and hung them in his studio, where they could be seen by visitors. They were certainly familiar to his students, which included Michallon and Jean Victor Bertin, both of whom were teachers of Corot.

Achille-Etna Michallon (French, 1796–1822), Waterfall at Mont-Dore, 1818, oil on canvas, 16 1/4 x 22 1/8 inches, purchase, Wolfe Fund and Nancy Richardson Gift, 1994.

Michallon was the first winner of the Prix de Rome in the new category of landscape painting. The Met purchased this rare, scintillating painting in 1994, when Whitney was still a dealer and Thaw was beginning to aggressively fill the bare spaces on his walls with plein-air paintings. Most of Michallon’s paintings are in the Louvre (as well as 860 drawings and watercolors). This rare painting is in remarkable condition.

As Tinterow noted shortly after its acquisition: “Because Michallon died at the age of twenty-six, his fame as one of the creators of the new school of landscape painting was obscured by the shadow cast by his long-lived student Corot. But when the bulk of Michallon’s work was brought to light in 1930, historians were compelled to change their view. As René Huyghe wrote: ‘Corot remains a poetic miracle but he is no longer a historical miracle’” (“Recent Acquisitions, A Selection: 1994–1995,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 1995).

Tinterow further underscored Waterfall at Mont-Dore’s rarity as one of the few finished, signed, and dated paintings Michallon produced. Tinterow says Michallon probably saw this famous waterfall on his way to Italy in 1817. Thaw gave three Michallon paintings jointly to the Morgan and the Met, including two studies of trees that complement this work.

In the 2007 AAA interview cited above, Thaw noted: “some of these artists who did some of these plein-air oil sketches that I have did the most God-awful ‘machines’ that they sent to the Salons. You know, the big history paintings.” This condemnation applies to Michallon, who produced very disappointing large-scale paintings.

Corot and His Associates

Corot had entered Michallon’s studio in the spring of 1882. When Michallon died in September, Corot studied with Bertin, who had also been Michallon’s teacher.

Camille Corot (French, 1796–1875), Mountainous Landscape, oil on paper, laid down on canvas, 8 1/4 x 16 inches, Thaw Collection, jointly owned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Eugene V. Thaw, 2009. Neither the date nor the site where this sketch was made have been identified. As Corot matured, his finished paintings possessed the soft features of sketches like this one, though with a pronounced silver-blue tonality.

Whitney’s two Corot sketches and the five from Thaw (donated jointly to the Morgan) greatly strengthened this aspect of the Met’s Corot collection, which now totals 39 paintings. Some of these sketches are usually hung in close proximity to a group of Michallon paintings in gallery 805; others can be seen in the Corot gallery (803).

Installation shot of gallery 805, with paintings by: Michallon, Corot (2), de Gazeau, Michallon, Leprince, Leprince, and d’Aligny. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

Incidentally, Thaw also sold a study of oak trees in the Fontainebleau forest to the Met in 1979. Not one to waste a good study of trees, Corot utilized this sketch in his Salon painting Hagar in the Wilderness (1835), situating oak trees in the middle of a Palestine desert! Unlike most of his contemporaries, Corot replicated the vigor and — in this early period — the plasticity of his sketches in his large paintings.

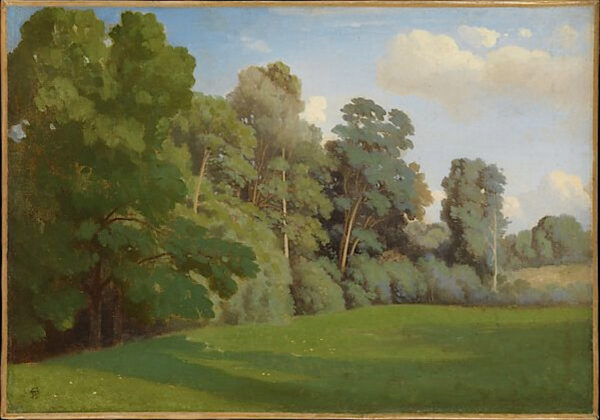

Théodore Caruelle d’Aligny (French, 1798–1871), Edge of a Wood, c. 1850, oil on canvas, 10 1/8 x 14 1/4 inches, The Whitney Collection, gift of Wheelock Whitney III, and purchase, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, by exchange, 2003.

The Met’s strong assemblage of works by Corot provides a context for the work of artists who were closely associated with him. Aligny had worked beside Corot in Italy and in the forest of Fontainebleau in the 1820s. As Miller notes in his entry on the Met website, the tonalist suppression of detail owes something to the example of northern artists working in southern Europe.

In this detail, we can see how Aligny’s effects approached Impressionism, with relatively discrete touches of color.

Charles Marie Bouton (1781–1853), Gothic Chapel, oil on canvas, 18 3/8 x 15 1/4 inches, The Whitney Collection, promised gift of Wheelock Whitney III, and purchase, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, by exchange, 2003.

In addition to the history painter Jacques Louis David, Bouton studied with the landscapist Jean Victor Bertin and the panorama painter Pierre Prévost. Together with Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (the future photographer), he created enormous panoramas that were illuminated by colored lights. His varied experiences enabled Bouton to endow a carefully composed, small interior like this one with immense theatricality. Miller notes on the Met’s website that Bouton exhibited a painting fitting this description in the Salon of 1824. Bouton’s painting makes a good contrast with sketchy interiors donated by Thaw, by artists such as Granet, Jean Antoine Constantin (called Constantin d’Aix), and the Danish painter Wilhelm Bendtz.

Rome and Naples

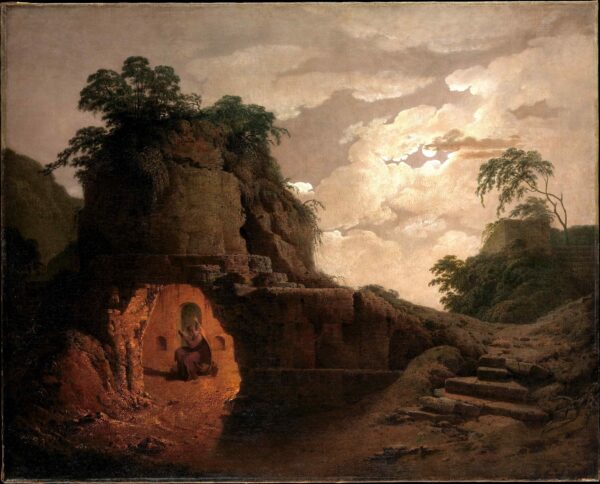

Joseph Wright (Wright of Derby) (British, 1734–1797), Virgil’s Tomb by Moonlight, with Silius Italicus Declaiming, 1779, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 inches, purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, gifts of Mrs. William M. Haupt, Josephine Bay Paul, and Estate of George Quackenbush, in his memory, by exchange, The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Gift, and funds from various donors, 2013.

Wright of Derby was in Italy from 1773 to 1775, and he visited Naples in 1774. He exhibited this solemn and moody painting at the Royal Academy in 1779. Wright painted as many as six versions of this subject, which was very popular with English clients. According to Sotheby’s, which sold this painting for 1.5 million British pounds in 2011 (the Met subsequently bought it from a dealer), it is Wright’s prime version of this composition, as well as one of only two with the figure of Silius Italicus. It is the museum’s first painting by Wright of a nocturnal setting. Sotheby’s calls it “one of the most iconic images of the British Romantic Movement.” Of all the paintings that have come up for auction after the acquisition of the Whitney collection, I think this highly important painting was one of the best fits for the plein-air galleries.

The Romantic/classical subject complements the northern paintings exhibited with it in gallery 806, many of which are set in Naples, including Virgil’s Tomb, Naples (c. 1818) by the German artist Franz Ludwig Catel. Additionally, Gustaf Söderberg’s The Grotto of Posillipo, Naples (1820), depicts a scene located just below Virgil’s Tomb. Wright’s work is, of course, softer, more evocative, and more mysterious.

Gustaf Söderberg (Swedish, 1799–1875), Rome with St. Peter’s and Castel Sant’Angelo, 1821, oil on two sheets of paper, laid down on Masonite, 8 3/8 x 14 1/2 inches, Thaw Collection, jointly owned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Eugene V. Thaw.

Söderberg, who had studied with Michallon, was the first Swedish artist to make plein-air paintings. While many art lovers are familiar with this view of the Tiber through the famous sketch by Corot from c. 1826-27 in the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, it might come as a surprise that Söderberg’s version was painted several years earlier. Nineteenth-century artists were very familiar with this view via prints, which served as crucial source material prior to the advent of photography. The Met’s website notes that one tourist described his first sighting of this view in Rome as “half recognition and half surprise.”

Johan Christian Dahl (Norwegian, 1788–1857), An Eruption of Vesuvius, 1824, oil on canvas, 37 x 54 3/4 inches, Gift of Christen Sveaas, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary, 2019.

The Dahl that Thaw gifted in 2007 (linked above) was the first of a remarkable eleven paintings by the Norwegian artist — who was a friend and neighbor of Friedrich — to enter the Met’s collection. Perhaps the most impressive of these is the large oil on canvas called An Eruption of Vesuvius, which was commissioned by the future Danish King Christian VIII. Dahl had witnessed Vesuvius erupt on December 20, 1820. Christen Sveaas also donated two other Dahls and a large, moody, moonlit view of North Cape by Peder Balke, Dahl’s protégé.

Vulcanologists will also be happy to learn that an even more dramatic eruption painting by the famed volcano painter Pierre Jacques Volaire has been promised to the Met by Howard and Nancy Marks in honor of its 150th anniversary, and that a volcano exhibition is in the works.

The Nineteenth Century Galleries in Context

If Whitney set the table for plein-air painting at the Met, Thaw transformed the museum’s presentation of it (and related paintings) into a feast. This visual feast is continuously enriched by new dishes provided by purchases and gifts. When the André Meyer Galleries opened in 1980, John Russell sounded a rare critical note in the last third of his New York Times review. Noting the lack of paintings by non-French artists, he listed a number of artists whose work he thought should be represented in the collection. When Whitney’s gift was announced, it was noted that his collection included a number of artists that were otherwise not thought to be in U.S. museum collections. That number of otherwise unrepresented artists was greatly increased by Thaw’s gifts. Russell would likely be delighted and surprised if he could see the diversity and depth the collection has attained since 1980.

Théodore Gericault (French, 1791–1824), Evening: Landscape with an Aqueduct, 1818, oil on canvas, 98 1/2 x 86 1/2 inches, purchase, gift of James A. Moffett 2nd, in memory of George M. Moffett, by exchange, 1989.

Since the opening of the Meyer galleries, the collection has also been augmented in other key areas. In 1980, for instance, it had only one small genuine Gericault and a nude study misattributed to him. The museum acquired a major landscape with small figures by him in 1989 (pictured above); a wonderful sketch of lions in 2011 (the version in the Louvre is now thought to be a copy); and a woman riding a horse that came with the Wrightsman bequest in 2019.

Shockingly, in 1989 the museum trustees were against the purchase of Gericault’s Evening: Landscape with an Aqueduct (1818). Just before Tinterow (then the Engelhard Associate Curator of European Paintings) was to give his presentation to the trustees, director Montebello warned him: “This isn’t going to fly. They [the trustees] don’t like it.” Tinterow recounts how a board member explained their about-face in the video An Acquiring Mind: Philippe de Montebello and The Metropolitan Museum of Art (discussion of the painting begins at 18:40): “If the director, the departmental chairman, and the curator of French painting say that this is a capital work that we must acquire, who are we to disagree with them?” He continued: “And with that withering statement, approval was given, and in fact we were able to get it for a pittance, for a very small sum compared to the value of it in the history of art.” The painting — which I regard as one of the most important purchases the museum has ever made — went for $2.42 million at Sotheby’s.

Like the Whitney collection, Gericault’s Evening: Landscape with an Aqueduct was economically undervalued. It, too, was acquired by exchange — through the sale of a weak Renoir — and it is credited as the gift of James A. Moffett 2nd, in memory of George M. Moffett. The important painting by Wright of Derby (discussed above) was also partially acquired through the exchange of works given by three other donors. Likewise, the remarkable Michallon Waterfall discussed above was also partially purchased by exchange. We can contrast the responsible and canny deaccessioning carried out under de Montebello to the reckless actions — and the additional plans that were fortunately stymied — undertaken during Hoving’s tenure as director.

Early in the Met’s history, many of its trustees and officials had a longstanding hostility to Impressionism and later art. The term was even used as an epithet for progressive trustees when they tried to oust the museum’s quixotic first director in 1895. “If they succeed the conservative force will go and the museum will be run by the impressionists,” declared Henry Marquand, the museum’s second president (Calvin Tompkins, Merchants and Masterpieces, 1970).

Notwithstanding some early gifts and even a few purchases — the latter of which put the enterprising curators in grave peril — the core of the Met’s progressive nineteenth-century paintings collection (as opposed to the conservative academic painters) was provided by the Havemeyer bequest in 1929, which had many areas of strength from Courbet to Cézanne. The museum regretfully rebuffed multiple offers of loans (which might have translated into gifts) from the great collector John Quinn.

Alfred Barr of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) pointed out in 1934 that the Met had no paintings by Gauguin, Seurat, Toulouse-Lautrec, or Henri Rousseau — as well as younger artists such as Matisse, Picasso, and Modigliani. At this time, some key Met trustees and officials were still very hostile to Post-Impressionism.

MoMA, which was founded in 1929 (contemporary with the Havemeyer bequest), was committed to the modern. A proposal that the Met would purchase works from MoMA — once they had become “classic” and were no longer modern — gradually gained support at the two institutions. Through an agreement that was in effect from 1947-1953, the Met purchased 40 works from MoMA, including Picasso’s Women in White (1923). When Eugene V. Thaw learned of Hoving’s plans to sell it and other important paintings in 1972, he notified the New York Times, which initiated the deaccession scandal noted above. John Rewald, a scholar of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism who was Thaw’s whistle-blowing partner, penned an essay titled “Should Hoving be Deaccessioned?” in Art in America in 1973.

The Annenberg collection serves as a second, complementary core collection of blue chip Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. Most importantly, it strengthened the Met’s relatively sparse holdings of Gauguin and Toulouse-Lautrec, it added needed late works by Cézanne and Monet as well as a rare Seurat, and it brought a very impressive group of Van Goghs to a collection already rich in works by the Dutchman.

The Metropolitan’s collection became uniquely diverse through the acquisition of the Whitney and Thaw collections, which include many little-known artists from France, as well as numerous artists from other European nations. The latter two collections also provided a bridge from the Prix de Rome winning artists who sketched in the Italian countryside to what became the avant-garde. The museum’s collection has also grown through the addition of smaller collections, as well as individual pictures, both great and small. Closure forced by the pandemic put a damper on the Met’s 150th anniversary last year, so it has been extended into 2021, and the nineteenth century European painting collection can be celebrated as one its glories.

Deaccessioning for “Care” rather than Acquisitions in 2021

The mere prospect that the Met might take advantage of the relaxed AAMD guidelines (and use the proceeds from sales of art for collection care) was met with outrage. Critics of this course of action noted the wealth of the museum and of its current and potential benefactors. They argued that the temporary measure was meant to assist vulnerable, underfinanced museums in a unique crisis. Critics held that the Met had no compelling need to avail itself of this opportunity, and that the precedent-setting consequences would be dire for the entire museum world in the U.S., since trustees would pressure directors and curators to sell art to pay bills.

Thomas P. Campbell (currently the director of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco), who succeeded Montebello as the Met’s director in 2009 and served until 2017, noted his dismay on Instagram. He feared that if the Met sold art to finance collection care, it could “become the norm.” Not one to mince works, Campbell likened this practice to “crack cocaine to the addict — a rapid hit, that becomes a dependency” (he is quoted in Robin Pogrebin, “Facing Deficit, Met Considers Selling Art to Help Pay the Bills,” New York Times, February 5; 7, 2021). On February 19, Campbell spelled out his objections in an Apollo article titled “American museums should not be selling their art to keep the lights on.” He fears the following: the temporary policies could become permanent; the AAMD’s ability “to police” future deaccessioning practices could be compromised; boards and other entities such as municipalities could use these regulations to evade fiduciary responsibilities; the principle that museum collections “are not taxable assets could be overturned”; the charitable tax deduction for gifts to museums could be challenged. Most objects in U.S. museums were donated by individuals. As Campbell notes, these donors expected their gifts to be memorialized in perpetuity on a credit line. Such credits are attached to objects bought in exchange (as I have noted several times above), but they cannot be attached to short-term “care” in the same matter. Campbell concludes that although the AAMD has acted with good intentions, it has “opened a Pandora’s box.” I agree with him on every point.

Lee Rosenbaum, in her CultureGrrl blog, is perhaps the most persistent and outspoken critic of the relaxed AAMD guidelines, which she regards as an abrogation of inviolable principles. She is also highly critical of the Met’s decision to capitalize on these temporary guidelines. For the latter, see “Pandemic Polemics: Metropolitan Museum’s Off-Key NPR Message vs. Cleveland’s Harmonious Storage Show,” March 1, 2021.

Rosenbaum also warns that the new practices have drawn the scrutiny of the New York state attorney general’s office. James Sheehan, chief of the attorney general’s Charities Bureau, contacted Rosenbaum to avail himself of her expertise on this subject (“Cue the Regulators! Met’s Deaccession Regression Attracts the Critical Eye of NYS Attorney General’s Office,” March 5, 2021). As noted above, Hoving’s transgressions in the early 1970s caused the attorney general to investigate the Metropolitan, which resulted in a host of new policies. Regardless of what the AAMD does in the future, the state attorney general’s office can impose its own restrictions.

Rosenberg is also a defender of permanent museum collections. She is often highly critical of ill-considered deaccessions, which she calls “deplorable deaccessions,” even when they were made in accordance with the old AAMD guidelines. Some of her commentary on this subject is linked in “The Year in CultureGrrl, 2020 Edition: It’s not over until the Deaccession Diva sings,” December 31, 2020.

Christopher Knight, a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, and Brian T. Allen, a former museum director, each wrote hard-hitting, extended critiques of the Metropolitan. Knight warned that if the Metropolitan crossed this deaccession Rubicon, museums “everywhere… will follow the Met’s lead” (“Commentary: While the Met contemplates selling its treasured art, rich trustees sit idle,” Los Angeles Times, February 14, 2021). While the Met projected a $150-million shortfall (in slightly more than a year) due to the pandemic, Knight emphasized that the wealth of U.S. billionaires increased $1.1 trillion — a nearly 40% growth — in 10 months. He noted that Michael R. Bloomberg’s wealth alone increased by $6.9 billion between mid-March and mid-October of 2020. With just 2.25% of that pandemic windfall, says Knight, Bloomberg could erase the Met’s projected shortfall. And, of course, the museum cut costs, so that it did not have a $150 million deficit. (Allen calls the $150 million figure a “canard.”)

Knight pointed out that the relaxed AAMD guidelines serve to undermine the museum’s raison d’etre: “Selling art from the collection to pay the bills is tantamount to eating the seed corn. A museum’s collection is the reason it exists.”

Brian T. Allen says the relaxed AAMD guidelines, which “would have been considered ghastly a couple of years ago,” were panic driven measures intended for under-funded museums whose survival could be imperiled by the pandemic (“Shame on the Met’s Trustees,” National Review, September 23, 2021). He estimated that the stock market’s recovery had brought the Met’s endowment to around $4 billion (neither he nor Knight were able to get budgetary information from the museum). Allen also reported that the Met was planning to sell another $5 million in art to use for collection “care” (in addition to the photographs and prints — estimated at $1 million or more — that spurred him to write his article).

Allen is concerned that the Met’s participation in this scheme will influence the AAMD to make its relaxed guidelines permanent. In his estimation, the Metropolitan, formerly “the gold standard of museum behavior,” has become “the museum world’s newest gold digger” and “the world’s artsiest welfare queen.”

In September of 2021, the Metropolitan’s Marina Kellen French Director Max Hollein clarified that proceeds from deaccessions would be used to “support salaries for collection care staff” (Katya Kazakina, “The Met Museum Is Deaccessioning $1 Million Worth of Photos and Prints to Fill a Revenue Shortfall Caused by the Pandemic,” Artnet News, September 17, 2021).

The Met’s 2020-2021 Annual Report: What it Says and Doesn’t Say

Each year, I eagerly await the Met’s annual report, which is released on November 10. I planned to study the financials to assess the Met’s financial health, and to use that information to discuss the museum’s decision to avail itself of the relaxed AAMD guidelines. I was disappointed to find the most meager report in decades, one that lacked information that had been readily available in reports from the last 40 years, which is as far back as my collection of annual reports goes. (The annual reports went online-only in the early 2000s, and the last ten can be accessed here). This year’s report (which covers the fiscal year from July 1, 2020, through June 30, 2021) is a mere 20 pages. Last year’s report, by comparison, was 110 pages.

I was initially dismayed to find that the financial reports were lacking, but it turns out that they had been spun off — for the first time — into a separate 26-page document this year, which can be accessed here.

On page 26, the net endowment assets for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2021 came in at a staggering $4.348 billion, an impressive increase from the $3.262 the previous year. So Allen’s prediction about the recovery of the endowment was accurate — it came boomeranging back.

In the annual report, President and Chief Executive Officer Daniel H. Weiss and director Hollein summarize how the museum’s financial situation has been affected by the pandemic. They built up an emergency fund of about $100 million and received federal aid through the Cares Act and Shuttered Venues Grant. The Met’s unrestricted revenue in fiscal year 2021 was $24.4 million, whereas it was $51.8 million in 2020 and $93.4 million in 2019. These numbers reflect a significant loss in admissions and membership income. Concomitantly, the Met reduced its expenses to $250.5 million, down from $287.6 million in fiscal year 2020 and $305.5 million in 2019. The museum reported operating deficits of $7.7 million in fiscal year 2020 and $7.6 million in fiscal year 2021. All things considered, the Met appears to be in a very good place economically, which begs the question of whether it really needs to sell art to pay expenses.

The annual report notes that on March 2, 2021, the Met’s trustees revised its Collections Management Policy to enable it to use funds from deaccessioned art “for the direct care of items in the Museum’s collection,” in accordance with the relaxed AAMD guidelines. It further states that in the fiscal year ending June 31, 2022, it will use $7,186,078.80 from deaccessioned art for collection care.

Seven-plus million dollars is not an inconsequential sum, especially when it is spent wisely, as it was in the instances I noted during Montebello’s directorship. In its annual report, the museum thanks two-dozen donors for the works that are being sold to fund collection care. Most are long dead. Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, the only woman among the museum’s 106 founders, was a donor of paintings and the first woman to be named a Benefactor to the museum. She died in 1887. Edward C. Moore, a designer for Tiffany’s who gave the museum an extraordinary collection of decorative arts, died in 1894. We can be certain that they — and all of the other donors whose names are familiar to me — will not object to the use made of their benefactions. The dead tell no tales. Nor do they object to relaxed museum guidelines.

Since the Met is by far the wealthiest and the most prestigious museum to utilize the relaxed AAMD guidelines, and since its existence is not threatened by its current economic situation, we have every reason to object to its participation in this scheme.

In its just-released annual report, the Met notes several five-year strategic goals for 2015–20, including this one: “Attain organizational and operational excellence to enable greater transparency, efficiency, collaboration, and communication.” In terms of transparency and communication, I give the museum poor marks for the way it has handled its utilization of the new AAMD guidelines. The truncated annual report also represents a backwards leap in transparency and communication.

I hope that Campbell’s fears are not realized. But if they are, the Met’s decision to utilize these new guidelines will go down in infamy. The Met is so big and so rich that any decision it makes on this matter will not affect it greatly. But the example it sets could prove catastrophic for other museums. While Hoving gave deaccessioning a bad name, the damage he did was limited to one museum. Hollein could go down in history as the deaccessioner who opened the floodgates that brought countless museums to ruin.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has taught at five universities, curated more than 30 exhibitions, and written or contributed to 19 catalogues and books. He taught courses on the Metropolitan at the University of Texas at San Antonio, and as a visiting professor at Sarah Lawrence College, he toured his students through the Metropolitan on a weekly basis.

7 comments

Cordova’s warnings about the impact of the AAMD’s revised guidelines regarding funds generated by collection deaccessions and the Met’s precedent setting model of the guidelines’ applications are warranted. Unfortunately numerous small and medium-sized art museums (which have been systematically excluded from the AAMD…a museum must have minimum operating budget of $2 million to be an AAMD member)) have for more than a decade pursued applying funds from deaccessioning to annual operating costs or bolstering failing endowments. Cannot the AAMD reverse itself? Or, at least, provide leadership on policy limitations to the two year period? Cordova is right that too many in the art museum profession look to the Met and smilier large museums as trend setters. Perhaps that view has always been a bit misdirected.

Excellent writing Ruben.

Thank you for your comment, Peter. The big danger is that trustees, directors, and city bureaucrats (those who are not operating with the best long-term interest of their respective museums) will advocate selling off the best art objects to balance the budget. This, of course, has already happened at too many museums, but now these misguided officials (or bad actors) can point to the Met and say: “They’re doing it, so it must be O.K.”

Thanks, Gaspar. I’m gad you enjoyed the article. I’ve been following the Met closely since the late 1970s, and it has been amazing to see all the changes that have transpired at the museum.

Thanks to you and individuals like Peter can keep some of these secretive Museum affairs in the open and people that are not aware of what goes on behind Museum’s close doors are made aware. Again thank you Ruben.

Great article Ruben. I learned new information from it.

You are most welcome once again, Gaspar. Secrecy did not serve Hoving well, and I do not think that it will serve the present administration, either. Thanks, Clif. I am very pleased with the responses I have received on Facebook and via messages. I had thought that only a few former students and a handful of like-minded nerds would be interested in the material in the article.