For Part One in this series, please go here. Part Two is here, Part Three is here, Part Four is here, Part Five is here, and Part Six is here.

We all know there’s this. And then there’s that. Your here, is no doubt someone else’s there. Today, Karen Mahaffy considers slippages of space and place — engagements with the membrane that separates one world from another — and dives in to how it feels to be in two places at once, or at least how to see into the same place twice.

Glimpses, submersions, unmoored glances — all are conduits to that other world that rests so easily inside this one — so comfortably inside that only the shock of recognition provided by the sudden confrontation of it in art and in life recalls us to its presence. These “liminal spaces” —domiciles becoming art galleries becoming domiciles; projections re memories that aren’t projections — they tell us a lot, including the daily iteration — we’re the ones who are here.

Karen Mahaffy

Sala Diaz is not the first house-space that I can recall encountering. It was not the first living-space-turned-gallery that I had ever visited, or even the first I had ever shown in. However, it was the first space of its kind through which I came to recognize and appreciate the important duality of a house-space.

The inherent value of this recognition may very well begin and end for me in Sala Diaz’s context within the Compound, which for those who don’t know, was a collection of historic, side-by-side apartments that were cheaply, brilliantly, fabulously occupied throughout recent decades by a host of artists and other creatives, and of which Sala was an essential part. But, I do love a good duality, or more accurately the liminal space implied within the dash between house and space. So much happens in that space that is worth exploring.

As a former resident of the Compound, my experiences between living there and visiting there are hopelessly intertwined. Thinking about Sala, I find myself floating less through its history and more through its memories. In this, I know I am not alone. The collective and individual memories created and the stories told and heard about time spent in and around Sala and the Compound by “generational” waves of residents and visitors all work to create its patchwork history. A history of people and ideas and growth and loss — all thankfully held down by some concrete points in the timeline.

It’s really difficult to pick one thread of memory to follow. And it’s equally hard to refrain from attempting to stitch it all together in a personal attempt to illuminate each memory gathered on a porch, huddled around a fire pit, or seated along a long, loud, table; loved. It has all been called a living sculpture, and luckily it was/is comprised of those many participants, who each contributed, who each remember, and who each have a piece of the story to tell. Sala Diaz formed in this way, as people gathered around it and lived in close proximity to it, in houses of a similar age. We are all intimately acquainted with its qualities.

When a place slips its category, how do we seek to understand it? Liminal experiences of place strangely recall for me memories of the church my family attended when I was young. Church service — as “nice” and Protestant-Congregational as it was — made me squirm under its buttoned-up, smiling veneer. My categorical sense of “church” shifted ever so slightly when I snuck in to touch the velvet and brocade-covered furniture in the parlor where the adults had after-service coffee; and exponentially more so with the occasional stolen glimpse through an open door into the rectory. That someone actually lived in the church — when everyone else was emptied from the place — was beyond compelling.

Shows that have acknowledged Sala Diaz (intentionally or unintentionally) as a former domestic space have been among my favorite experiences there. An installation by Andrea Caillouet, simply titled Sala, stands foremost amongst them and is one that resonates with me still. Until writing this, I don’t think I have ever remembered to tell my dear friend how often I think of this work.

For Sala, each of the space’s two main rooms were recomposed by Caillouet through painstakingly prepared and deliberately hued walls, chandelier-like fixtures and carefully selected door knobs, all of which silently evoked the rooms’ prior life. Large-scale photos of “other interior spaces,” mounted on plexiglas and backlit, were installed into the existing doorways. Doors echoing doors…echoing doors. Scenes of household objects, arranged in quiet proximity to one another, felt like stolen glimpses into someone else’s intimately curated life.

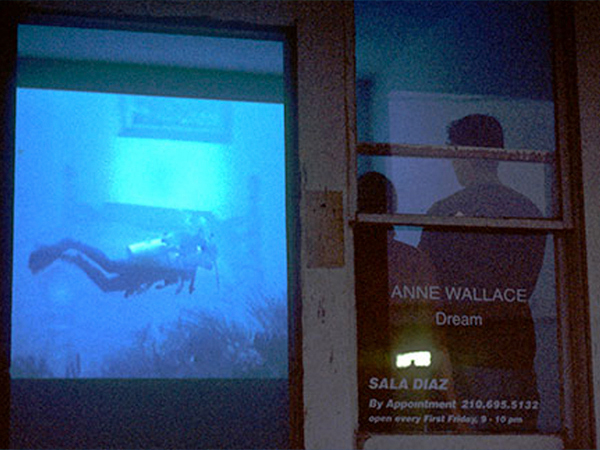

Floating backwards in time, Anne Wallace’s exhibition, Dream, is one of my earlier memories of being at Sala Diaz. With the reminder provided by the archives being gathered for UTSA and the show currently at the gallery, I now know that I had certainly attended other shows at Sala Diaz prior to this, but until present this work lived unmoored in my own foundational memories of the space. It was before my time living at the Compound and before even knowing Anne very well; it was a salient moment when I recalled feeling how a work can resonate in an exchange with space itself.

In Dream, a video work was projected to cover one wall of the front room of Sala, and could also be glimpsed from the front yard, glowing blue through the window, creating silhouettes of the figures inside. In the piece, a scuba driver moving fluidly through blue water is overlaid onto scenes of empty rooms in a family home. I swear as you entered the front door, you could feel the pressure shift — air to water; house to gallery.

My experience of seeing this work is tethered to my own childhood memory of staying in a rented beach house that my family had to evacuate upon learning of warnings of an impending hurricane. I vividly recall the (adult) explanation of the house possibly and suddenly becoming submerged conjuring visions of coming back to swim through those foreign rooms and halls; of hovering buoyantly in a way I was never meant to inside a home.

I would learn much later that Wallace’s video, entitled, You breath differently down here, was as she writes, “about childhood, memory, and the tragic death of [her] younger sister from a surgical error.” It was the result of a vivid dream she had of swimming through the house they grew up in. The diver swims slowly as the camera pans across vacant rooms; the only sound, the diver’s respirator, fades into to the rhythm of a life-sustaining ventilator. Color and sound filled each room in the video and gallery equally; cool blue light, rhythmic silence and breath, and the feeling of submersion floor to ceiling.

This work is possibly a most fitting analogy of the liminality of Sala Diaz: a space that is at once familiar and novel, old and evergreen, home and not home. We entered and floated through those rooms, each time in way that was unintended in their original function. The space is continually transformed through the accumulation of ideas and memories and loss and change. Our living archive.

Next week: Yunhee Min

1 comment

Nice.