Installation view of Without Limits: Helen Frankenthaler, Abstraction, and the Language of Print, on view at the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin

Print is a complex social media, and has been for millennia. From early movable type to lithography to photocopying, humankind has long experimented with ways to transfer images from one source to another, creating new images and texts in the process. There are many ways to produce what we might today call “print” — contemporary artists and printmakers continue to investigate how to challenge notions of print, and how to connect print with audiences.

American Abstract Expressionist painter Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011) began exploring prints and printmaking in 1961, bringing her decade of experience in color-field painting to her then-new work. (Frankenthaler’s first soak-stained piece was 1952’s Mountains and Sea; the piece’s tension between spontaneity and intentionality would be a consistent theme in Frankenthaler’s later print works.) In Without Limits: Helen Frankenthaler, Abstraction, and the Language of Print, at the Blanton in Austin, we see how Frankenthaler’s work fits into the “printmaking renaissance” of the mid-20th century, and we’re reminded that printmaking is an inventive and intricate medium.

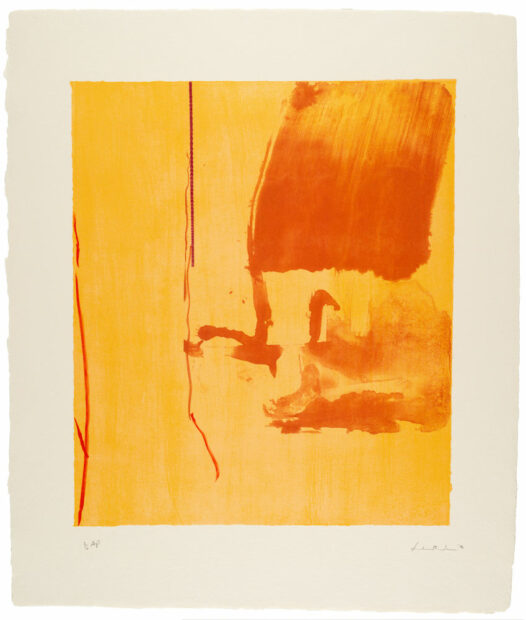

Helen Frankenthaler, Harvest, 1976, AP 3/10, six color lithograph, 26 x 22 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation

Without Limits combines ten of Frankenthaler’s prints (and six of her proofs) with several other artists’ works from the 20th and 21st centuries. One of the most striking aspects of Frankenthaler’s printmaking is the variety of different printing techniques she employs. From lithographs to screenprints to etchings to woodcuts to pochoir, each technique allows a printmaker to play with color, space, and texture, and the versatility and flexibility of Frankenthaler’s printmaking is particularly striking between different pieces.

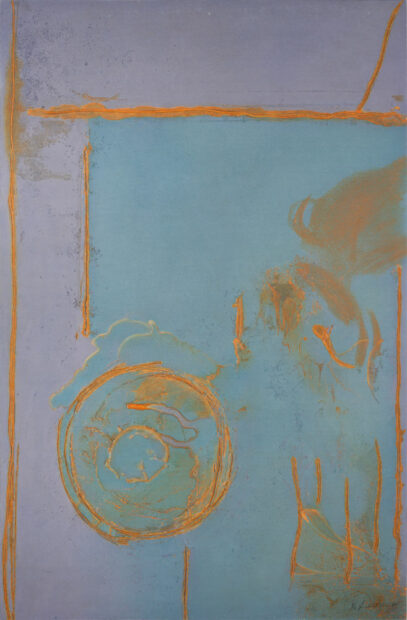

Helen Frankenthaler, Guadalupe, 1989, Ed. 9/74, three color Mixografia, 69 x 45 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation

Helen Frankenthaler, Japanese Maple, 2005, AP 5/12, sixteen color woodcut, 26 x 38 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation

The warm colors of Frankenthaler’s Harvest (1976) proofs, for example, are bookended with two pieces that utilize black — rather than ocher-like — ink. Guadalupe (1989) explores mixographia to produce a three-dimensional print with a deeply embossed surface. Green Likes Mauve (1970) required a hands-on application of liquid acrylic to offer a “painterly quality” to the print — not quite a monoprint (one unique print), but much more so than a series of proofs, like Harvest. Frankenthaler’s work demonstrates just how malleable print is.

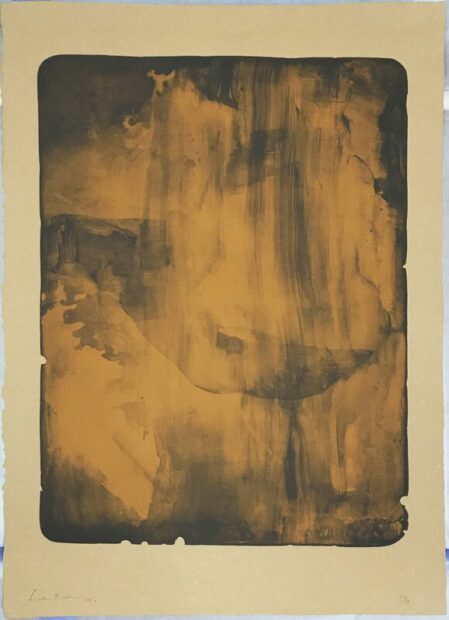

Perhaps the most striking Frankenthaler piece included in the show is Bronze Smoke (1978), a piece created from two stones — the first stone inked with a copper color, and the keystone inked in a black-gray color. “Frankenthaler achieves this diaphanous, smokey image by brushing and pooling tusche on the stone surface,” the exhibition text informs us. Tusche is a particularly greasy black ink used in lithography. “Bronze Smoke is part of a group of prints that suggest space using a limited color palette and layers, bands, or veils that stretch across the sheet.” The copper and black billow out from the page as tendrils of smoke seem to find their way into the corners of the print. Follow the smoke out to the print’s edges and it’s possible to find a darkened, uneven edge, as though the print has been burned. It’s as if Frankenthaler is putting wildfire to paper.

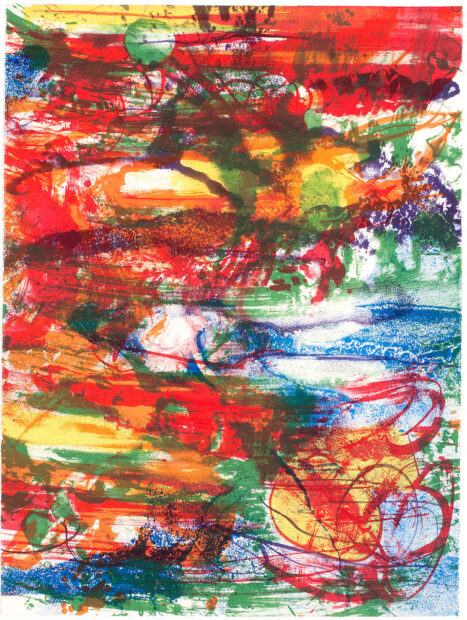

Carroll Dunham, “Green (4th),” from Red Shift, 1987–1988, Color lithograph from 18 stones and 22 plates, 30 x 22 1/2 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Purchase as a gift of Virginia and Ira Jackson, and through the generosity of the Still Water Foundation

But Without Limits is careful to situate Frankenthaler’s work within a broader context of 20th and 21st-century printmaking. In addition to Frankenthaler’s work, Without Limits includes pieces like Eric Avery’s The Last T Cell (1993), a relief photo-engraving and linocut over monotype; Carroll Dunham’s Green (4th), a color lithograph created from 18 stones and 22 plates; and Isabel Pons’ Untitled (1966), an embossed monotype print, to name a few. While Frankenthaler’s exhibited works build directly on her experimentation with color, all of the work highlights how print is a balance of color and space over time.

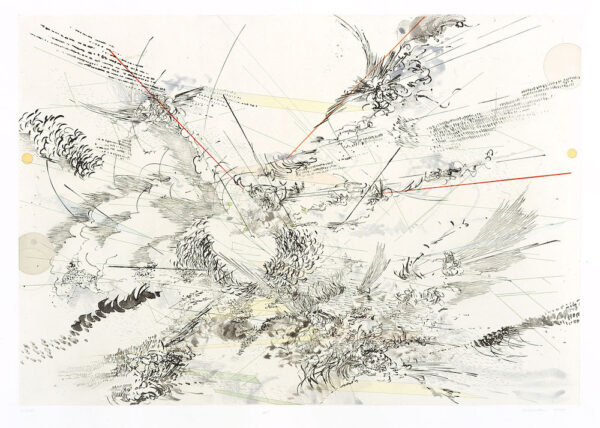

Julie Mehretu, Local Calm, 2005, sugar lift aquatint with color aquatint and spit bite aquatint, soft and hard-ground etching and engraving, 35 1/2 x 46 3/4 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Purchase, © Julie Mehretu

Without Limits also includes a print by Julie Mehretu, Local Calm (2005) — one of three pieces in a series titled Heavy Weather that explores the catastrophic 2005 Atlantic hurricane season. The print is a narrative “storm-scape” meant to invoke winds and water; the swirls of lines and colors have a focal point in the lower part of the print akin to a hurricane’s eye. But the spaces between the lines offer a bit of respite — a calm, perhaps — from the franticness of the rest of the piece. These pulses of lines and space remind audiences that weather (heavy weather, at that) is a series of starts and stops. Sixteen years on, however, it’s impossible to see Local Calm as anything but a harbinger of climate change.

From Helen Frankenthaler to Julie Mehretu to Eric Avery to many others, Without Limits offers audiences a powerful set of prints and proofs that feel judicious, current, and important in the present-ness of today’s Anthropocene. Print, we are reminded, is still very much a timely and social media.

On view through Feb. 20, 2022 at the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin.