Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

Artist Hannah Dean had this conversation with artist Alejandro Macias in Tucson, Arizona, where Macias is an Assistant Professor at the University of Arizona’s School of Art. Born and raised in Brownsville, Texas, along the U.S./ Mexico border, Macias’ work has been driven by his Mexican-American identity and the current social-political climate.

Raised in the Rio Grande Valley, Macias’ work addresses themes of heritage, immigration, and ethnicity, which are set in contrast to his critical engagement with the assimilation and acculturation process often referred to as “Americanization.” Since 2016, he has been the recipient of numerous awards and recognitions including residencies at Centrum in Port Townsend, WA, Vermont Studio Center, Chateau d’Orquevaux, and most recently The Studios at MASS MoCA. Upcoming shows in Texas include the Museum of Pocket Art and the AMoA Biennial 600 in Amarillo. His work is currently on view at the Tucson Museum of Art in the group exhibition, 4 x 4. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Hannah Dean: Are you enjoying teaching here in Arizona?

Alejandro Macias: Yes! It’s a tenure-track position. Tucson is a great place. I get along with my colleagues, it’s a great place to work. Everyone is so accomplished and you can feel their momentum. I hated leaving everyone I knew and leaving Brownsville, but it’s been good here.

HD: In Texas you lived right along the border, but Arizona is still definitely borderland. Do you feel a difference between these places as borders, specifically?

AM: There are a lot of parallels. When I was in Brownsville I saw myself reflected. Brownsville has a 90-95% Mexican-American population; I saw myself there. When I came here — it’s a much more diverse population. I guess I hesitated even making border work, or responding to the border. So many people were aware of the issues that were happening there [in Brownsville] whereas in Tucson they may not be. Maybe closer to the border, like Douglas [AZ] they would have a better understanding of what’s happening.

I’ve traveled and done residencies and I always get questions about the border, because the only exposure people get is through mainstream media. So yeah, there are a lot of parallels between Latinos [anywhere], but Brownsville is definitely more aware than Tucson. I make work about both areas, and about transition. And both places have natural obstacles for migrants seeking asylum. The border protections are one, but then you have the desert terrain where people literally disappear. They both have obstacles, but they’re different in nature.

HD: So what would you say to people who are only consuming media soundbites? What is missing in that conversation?

AM: Well, I think there is the fact of people literally being desperate for survival. Why would they take that risk unless they needed to? Imagine trying to cross countries knowing you might die in the process, which is very likely in the desert. I don’t think that is necessarily painted in the news. People lack sympathy. And surrounding border issues, I take it personally because my grandparents (though they eventually gained citizenship) were migrants. It’s very strange to see how people treat migrants, or are anti-immigration.

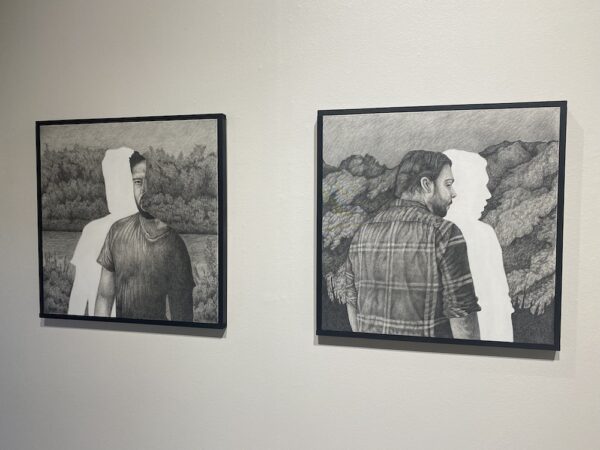

HD: You’re a portrait artist. Would you talk about some of the methodology to that? You often obscure the identifying features of the person, or there is a reference to the digital self.

AM: Yeah, various techniques are working with each other. A lot of portraits are split. I think this show [4×4] was highly personal. I always deal with self-portraiture, but there was more in this exhibition than in some others. But the split acts as a metaphor for the assimilation process. I came from a Mexican household, purely speaking Spanish as my first language. My mother was very religious, very traditional, especially with my grandparents. I spent a lot of time in Matamoros, Mexico. Then my mother put me in bilingual classes when I was 8 or 9. In the way I spoke I had an accent, pronouncing English words a certain way, and I think it came from my mother and her heavy accent. So as I was learning English I was mispronouncing words and was often corrected, even by my classmates. That almost felt like a mildly traumatic experience, where I was treated as alien or an outcast.

So I began putting all my emphasis into the English language and learning what a true American should be. I wasn’t entirely sure but I knew I needed to learn English. So the television was important. It wasn’t until later in life that I realized what the assimilation process was. Living on the border, you identify somewhere in between.

HD: So, you realized this was happening as an adult.

AM: Yeah, so I look back and reflect on it. If I wasn’t a visual artist, I don’t think I’d be able to think about it so much. Looking for a place of belonging, finding a community and culture to reflect on doesn’t just limit itself to Mexican culture; a variety of people have this struggle when they arrive here [the U.S.]. A lot of my work responds to that.

I found myself going to traditional, representational painting, grounded in realism, because that is what people respected [in Brownsville], but I started looking at Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, abstract figurative painters. I knew I wanted to be a figurative painter but I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with it.

So you see this split, and it’s also like the Rio Grande River — well, not “river,” because that’s redundant. The split is a reflection of place, and the assimilation process. You have the representational portion as well as something like the serape as a way to talk about heritage and culture. It feels very graphic, or very loose. The “Nopal En Frente” paintings are a response to what my mother told me growing up.

HD: And what’s that?

AM: It translates to “do you have a cactus on your forehead?” Like you’re running away from your heritage. She saw me as “oh, you’re trying not to be Mexican.” So the bottom half is rendered, and the nopal is very obvious but in a loose and abstract way.

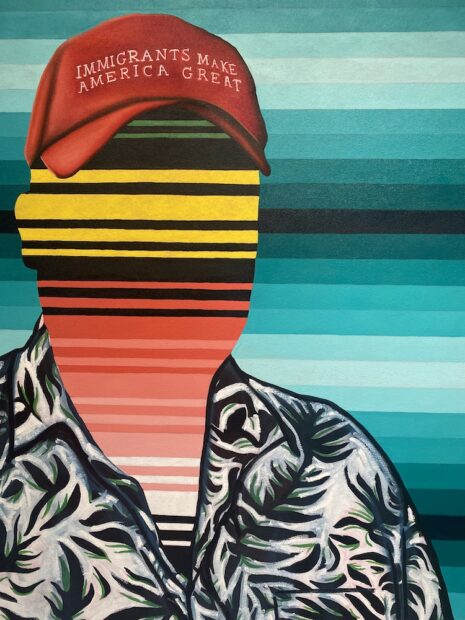

HD: The mark-making definitely opens up a lot of your work. Did the subverted MAGA hat portrait happen after the Nopales series? The brushwork in the shirt is new.

AM: That happened before! I had done the lines, but I didn’t want to do something that purely felt flat. That loose brushwork was me trying to make it work — very frustrating, actually!

HD: You’re using icons: a Hawaiian shirt, a Dallas Cowboys shirt, a Bud Light. All these things are culturally loaded. While your work is about Mexican-American identity, you really get at the fact that it’s not a monolith.

AM: It’s all very layered. There’s one painting where I use myself holding a Dos Equis bottle. I actually own that shirt, a hybrid of Captain America and the Hulk. You’ve got the “ultimate” image of an American patriot. And then you’ve got the Hulk, a hero that is sometimes seen as a monster and villain. They contrast themselves in the way they are perceived. I was thinking about my mentor [Carlos G. Gomez] who did a chupacabra series. In the way he talked about migrants, it was people looking for opportunity or a way of life, but who are often seen as invaders. They are from the night, seen as these monsters, but they are simply misunderstood.

I like that. The Dos Equis bottle gets at culture as well. And then the Cowboys shirt. It’s interesting to me when people cross over; it’s like they automatically love the Cowboys. America’s team, right? It’s almost like a religion. You drive around on Sundays and people would have their garage open, and everybody is wearing their attire and you see the tallboy Bud Light. It even fits the color palette! I wanted this work to be enveloped in Mexican and American pop culture.

HD: What’s next?

AM: Since I’m working in Tucson and don’t have to pay crazy shipping fees, I was able to work larger than I’ve worked before. Now I’m doing the opposite for the Museum of Pocket Art, these tiny little credit-card sized paintings. It’s challenging. I don’t even know if they’re good, but it’s a challenge. I’m not working on a body of work now, but playing.

HD: You use a lot of humor in your work.

AM: I want to be satirical. I want the work to interact with the viewer; I don’t want to spell it out for people. I hope they take the time to have a dialogue with the paintings, to get to the root. I know some people will identify with the images, or even the titles. I know the title “Nopal en Frente” will get through. In Mexico, it’s deemed a racist saying. I perceived it differently because of the way it was said to me. Although [the paintings] look very playful, there is something darker there. I want to infuse them with color and capture the viewer — but when you take a closer look, it goes far beyond laughter.