Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

Not so long ago, co-curators Ryan N. Dennis and Evan Garza were hoping to be able to call the 2021 edition of the Texas Biennial, which just opened at five sites across San Antonio and Houston, a “post-pandemic” event. We’re very much still mid-pandemic, of course, but the duo have pulled off an impressive program nonetheless, which officially opened on September 1 and will mostly remain on view through the end of 2021. (See the bottom of this post for exhibition dates.)

Both curators are Texan natives living out of state — Dennis in Jackson, Mississippi, and Garza in Washington, D.C. — and they have overseen a Texas Biennial that is unlike the previous six editions in several fundamental ways. For one, the traditionally very-Texas-focused artist selection process was loosened up a bit to include “Texpats” — locals who’ve moved out of state — and non-native artists who live and work in the state. About half of this year’s group of 51 participants are older, well-established artists personally invited by the curators to exhibit alongside the emerging and mid-career artists that responded to an open call. The curators did this explicitly to create an “intergenerational dialogue.”

The third major difference is geographical. Most previous editions of the Biennial have centered on Austin. While San Antonio has hosted standalone Biennial exhibitions before, this year’s program is overwhelmingly concentrated in the city, with components at the San Antonio Museum of Art (SAMA), Artpace, the McNay, and Ruby City. (The fifth Biennial site is FotoFest in Houston.)

This is partially thanks to the 2021 edition’s curatorial assistant and Exhibitions Coordinator, Rigoberto Luna, who advocated for increased participation by San Antonio institutions and has filled the crucial boots-on-the-ground role, overseeing installation and racking up miles on his truck transporting work. Luna is also the co-director of San Antonio gallery Presa House, and a key driver of the city’s grassroots art scene.

While the build-up to the Biennial opening was hectic, Luna told Glasstire during the installation at SAMA that the end result is a remarkable collage of voices from different places and times, coalescing in the current historical moment. “We’re standing in a room full of BIPOC artists,” he said, while San Antonio-based artist José Villalobos installed a gallery-spanning sculpture nearby. “Each conversation is slightly different, but they’re all kind of speaking on the same terms.”

Installation view at San Antonio Museum of Art: Work by Jose Villalobos in the foreground. Image courtesy San Antonio Museum of Art

Villalobos, who exhibited at the Transborder Biennial in El Paso and Juarez in 2018, and recently closed a solo show at Artpace, installed a provocative work in the center of SAMA’s biennial exhibition, an assemblage of soil, cement, rope, and flowers that meets work of different timbres and tenors in every direction. “I’m from the border, right, and just seeing the juxtaposition of certain works with my work is very interesting,” the artist told Glasstire during the installation.

Juxtapositions set in place to provoke a common, if increasingly nuanced, social conversation seems to be the over-arching theme of the 2021 Texas Biennial, entitled A New Landscape, A Possible Horizon. I caught up with the curators in August for a Zoom call to learn more about the creative departures they took from Big Medium’s usual Biennial format.

Josh Feola: I want to ask about some of the artists that you two selected, I’m assuming, based on your personal and professional experiences. One is Rick Lowe. He stepped away from his artistic practice for many years when he founded and was working at Project Row Houses — Ryan, I know you spent time in that organization. Rick Lowe has been very active with social and racial justice so I can see how he fits the high-level theme of this Biennial. In recent years he’s come back to his artistic practice. What was your reason for inviting him?

Ryan N. Dennis: I think Rick Lowe speaks to, first, a deep influence in Texas. He is from Alabama but he’s lived in Houston for over 25, 30 years. Many people also did not know that Rick started off as a painter. He started painting landscapes, and moved into activism through painting, and then founded Project Row Houses in a moment of… I wouldn’t say taking a break, but really just thinking about where his beginnings started. He revisited painting, and I think what Rick represents within the exhibition is our curiosities around materiality, wherein paintings serve as a kind of art historical and cultural arc within the exhibitions that are presented at, say, SAMA, where he is, but also at other institutions.

Evan Garza: The conversation that we’re having at SAMA is a painterly one, and Rick’s work is such an important part of that conversation. Activism is kind of a blood that runs through so much of this project, and the work by Rick that [is] on view at SAMA is called Black Wall Street Journey #3, which speaks to the Tulsa Race Massacre. For Rick, abstraction can contain a multitude of histories.

That’s also another theme that we’re really exploring throughout the Biennial — artists who are navigating both a present-tense and a past-tense at the same time in their work. Rick’s work is in conversation at SAMA with Trenton Doyle Hancock and Virginia Jaramillo, who is an El Paso-born painter, and they are all using color and they’re all using abstraction and they’re all using paint in fundamentally unique and also really common ways. His work was really suitable in that context.

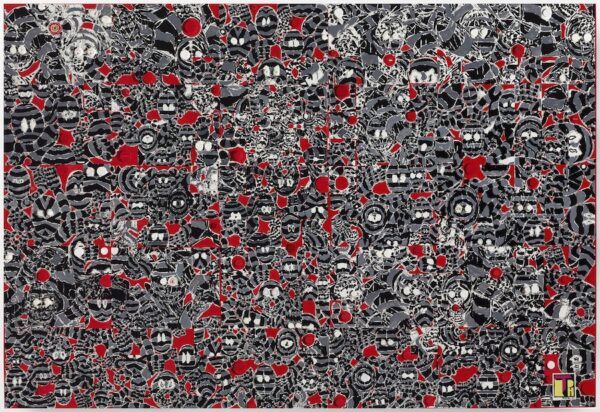

Trenton Doyle Hancock, Bringback Condiments: Ketchup, 2020, Acrylic, graphite, plastic tops, faux fur, paper collage on canvas, 90 x 132 in.

Credit: Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York. © Trenton Doyle Hancock 2021.

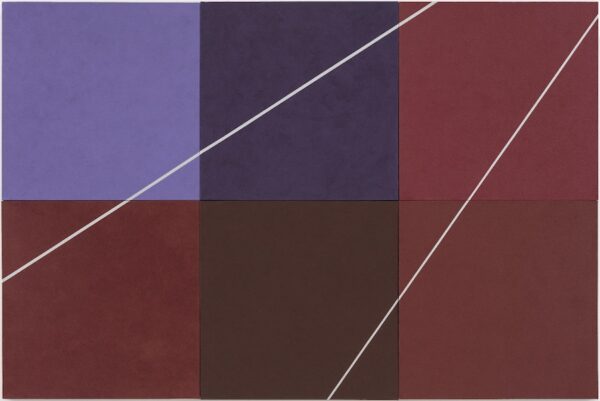

Virginia Jaramillo, Point Omega, 1973-2018, Acrylic on canvas, 172.7 x 259.1 cm, 68 x 102 in.

Credit: Image courtesy the artist and Hales, London and New York. © Virginia Jaramillo.

JF: The other artist I was curious about is John Gerrard, from Ireland. You expanded the parameters this year to include both “Texpats” and Texas-based artists who aren’t from here. Despite having done some site-specific work in Texas that I’m aware of — Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas) 2017, for example — this artist doesn’t fit either category really. Why did you select him?

EG: That was another invitation. For me, John’s work was incredibly unique among the artists considered because John’s work is a conversation, a meditation really, on the role that the Texas landscape has played within this larger narrative of climate change. That Spindletop, Texas work you’re speaking of followed the work that we’re [exhibiting] at the McNay called Dust Storm (Dalhart, Texas), which is an animation from 2007 that features a sculptural element. That work speaks to the Dust Bowl and how a combination of heavy drought and really shitty farming techniques created these incredible dust storms that were totally manmade. And the Spindletop work is a rumination on the fact that the entire petroleum industry, the origin point for that entire industry is in Texas.

Ryan and I are both from Houston; it’s an incredibly international city. It’s an immigrant city, and living there gives you a sense of the lives and experiences of other people. I can’t imagine anything having a more global impact in Texas than the petroleum industry. So, because we were so interested in expanding the parameters of artists to consider, we really wanted to engage international artists as part of this mix. Someone who is speaking of and from Texas, [but not] from within it geographically.

JF: One concern people have here is that when any artist or musician or filmmaker or anything like that starts to get a little bit big in San Antonio, they leave. They go to Austin, or New York or LA, or wherever. And that’s something people grumble about. I think that perception is a bit outdated, but I wanted to ask what you two think, since this program is heavy on both San Antonio institutions and artists.

RD: Honestly, I’m impressed with San Antonio. I grew up in San Antonio; I left the city when I was 18 and moved to Houston, lived in New York and moved back to Houston, and now I’m here in Jackson. But I will say, what has been incredible is seeing how robust the art scene is [in San Antonio]. In some ways, I don’t know if I was blinded before because I was from there and just didn’t give it as much attention growing up, but there was something kind of missing at some point in my teenage years, culturally and artistically. But what we see is some really incredible artists doing work in a hyper-localized way, which I love. I think the artists in San Antonio are speaking to communities in San Antonio in a way that feels really grounded, but also robust and rigorous in ways I’m super excited about.

EG: I just spent three weeks in San Antonio, and as someone whose entire family is from Laredo, I very much understand this notion of folks “making it” and then not coming back, or this impulse to move on to greener pastures. That is the most Texan question you could have possibly asked us, because I understand that sentiment completely.

RD: And people say that about Houston all the time!

EG: That’s where I was going with this! The same comment is actually made about Houston artists. That’s the best response that I can give to this question — it’s so not limited to San Antonio in this way, because Ryan and I both spent a great deal of time in Houston. I’m a Houston native. And this is the subject that also comes up in Houston as well.

On view at the McNay: Phillip Pyle II, Broken Obelisk Elbows, 2018, Digital print on paper, 39 x 27 in. Image courtesy the artist. © Phillip Pyle II 2018.

Specifically about the San Antonio art scene — I totally echo Ryan’s comments. I made it a point to walk through the collections and the other exhibitions of all of our exhibition partners, and the collections and the museums in San Antonio are off the chart. They’re just so impressive. Working with Rigo has also given us this view of what’s happening on the ground in the San Antonio art scene, how artists are supporting other artists so that their names can grow. There’s a legitimate Texas-style community of artists in San Antonio that are making it happen on their own.

And to that [earlier] point, we see the same thing happening in Houston. FotoFest has been an unbelievably generous partner to work with. We’ve worked really collaboratively with Max Fields at FotoFest, and I feel very strongly that the presentation there will be a really fantastic complement to the exhibitions taking place in San Antonio. When you’re from Texas, and from a Texas arts community — particularly one that has such deep local roots like San Antonio or Houston — the notion that artists that make it then go and don’t come back is one that will always exist, as kind of a hometown thing.

On view at FotoFest in Houston: Ja’Tovia Gary, THE GIVERNY SUITE (stills), 2019, film, 39:56 minutes, three-channel installation, stereo sound, HD and SD video footage, color/black & white, 1920 x 1080, 16:9 aspect ratio, dimensions variable.

Credit: Image courtesy the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. © Ja’Tovia Gary.

JF: One of the major curatorial thru-lines in this Biennial program is racial and social justice. There are different approaches to incorporating these themes into art spaces. For example, last month Hopscotch in San Antonio opened an “LGBTQ+-friendly” installation and held a First Thursgayz event with a $20 cover and Pride-themed cocktails. That seems pretty geared toward revenue to me. I see what you’re doing as obviously different, using art to create conversations around overlapping issues in a different way. How have you gone about trying to communicate this theme with the selection of the artists, and the selection and placement of individual works?

EG: Racial and social justice is really just one of the themes that we’re exploring as part of the Biennial. Others that are significant in some of the exhibitions include how materials can contain histories, artists who are working with archives, artists who are responding to immigration rights issues and activism, climate change.

RD: And the landscape.

EG: It’s part of why the project is framed in this way; there are so many points of entry into this conversation, and issues of racial and social justice are just one of them.

In the queer world, we call what you just described “rainbow capitalism.” It’s a way to use equality as a way of engaging in capitalism. As curators, it’s our job to explore the voices of artists, how they choose to respond to issues of the present, and issues of the past. It’s our responsibility to make space for those conversations to happen, and to carefully think about who are the artists and which are the artworks that may be best suited to have that conversation. And if this conversation is happening over here, about issues relating to immigration or the border crisis, how does that work relate to what Trenton [Doyle Hancock] is doing? What story is Vincent Valdez telling that Trenton can respond to in some way? What can Adrian Armstrong say that Virginia Jaramillo isn’t saying? To a certain degree, you’re creating a melting pot for these conversations to happen.

I would push back pretty hard in trying to compare apples to oranges in terms of what rainbow capitalism is versus what this project is doing, which is engaging the voices of artists.

On view at Ruby City: Ariel René Jackson, The next life of property, 2019, chair erected onto chalk rendering of US flag; Tampico broom corn via Mexico, Texas sourced soil, chalkboard paint, concrete, 60 x 36 x 48 in. Image courtesy the artist. © Ariel René Jackson 2019.

RD: I would add that it’s also, when thinking about those themes, it didn’t just happen now. Evan and I have been working within a social justice, public art, community-driven professional landscape since forever. It’s not reactive or responding to a hip moment. It’s embedded in, I think, every kind of project that we have authored, and organizations and institutions that we’ve been a part of.

EG: It’s really important to understand that, to a certain degree, all Biennials are responsive, but the nature of our work as curators is that these are issues and themes that are consistent across more than 30 years of work between us. And for that reason, because Big Medium chose to pair us together — which was a decision we didn’t make — we’re looking to the places among our curatorial practices where we see eye to eye. I have to say, it’s been not only a huge honor and a pleasure, but also the privilege of a lifetime to get to work with a curator who sees the same things that I do, and can also shed new light on the things that I see, and vice-versa. It’s a wonderful pairing.

****

2021 Texas Biennial venues and dates:

San Antonio

Artpace: August 5 – December 26, 2021

McNay Art Museum: September 1, 2021 – January 9, 2022

Studio at Ruby City: August 1, 2021 – January 30, 2022

San Antonio Museum of Art: August 19–December 5, 2021

Houston

FotoFest: September 2–November 13, 2021