Ill. #1: Detail of Ganesha from behind, “Buddha, Shiva, Lotus, Dragon: The Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection at Asia Society” installation, Robert LaPrelle, Kimbell Art Museum.

Buddha, Shiva, Lotus, Dragon: The Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection at Asia Society is an exhibition comprised of choice examples of sculptures, bronzes, ceramics, and metalwork assembled from the postwar 1940s through the 1970s by John D. Rockefeller 3rd (1906–1978) and his wife, Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller (1909–1992). This collection, which spans two millennia, was donated to the Asia Society Museum in New York in 1979. The 67 works featured in this exhibition range from China and India to present day Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, Korea, and Japan. Due to their fragility, sculptures fashioned out of wood and works on paper are not featured in the exhibition. Co-organized by the American Federation of Arts and the Asia Society Museum, this touring exhibition is at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth until through September 5.

“Every piece in the exhibition is an icon, an absolute jewel,” says Jennifer Casler Price, the Kimbell’s curator of Asian, African, and Ancient American art who organized the exhibition. She notes several themes within the exhibition, including “the transmission of Buddhism across Asia exemplified by fourteen sculptures.” The exhibition also traces the development and history of Chinese ceramics, “from the 8th to the early-18th century, with an especially strong representation of blue-and-white porcelain, including a very rare and important platter once owned by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, builder of the Taj Mahal.” Price also directs attention to “a grouping of five spectacular Chola bronzes from India.”

“There is something of wonder and discovery for everyone,” Price said, adding that it is “one of the greatest collections of Asian art in the world.” Many works in the exhibition serve as crystallizations of key philosophical and religious beliefs within multiple periods and cultures.

Since the Kimbell also possesses a remarkable collection of Asian art, Buddha, Shiva, Lotus, Dragon provides the opportunity to view highlights from two of the best small collections of Asian art in buildings by two of the greatest modern architects: highlights of the permanent collection are on view in the Kimbell’s Louis I. Kahn building (opened in 1972), while those from the Asia Society Museum are in the Renzo Piano building (opened in 2013). Of the Kimbell’s collection of 119 Asian works of art, 23 are currently on view. This review incorporates some works in the Kimbell collection that complement those in Buddha, Shiva, Lotus, Dragon.

“Buddha, Shiva, Lotus, Dragon: The Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection at Asia Society” installation, Robert LaPrelle, Kimbell Art Museum.

Catalogue

Adriana Proser, the former John H. Foster Curator for Traditional Asian Art at New York’s Asia Society Museum, who is currently a curator at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, wrote a 192-page catalogue expressly for the exhibition. Buddha, Shiva, Lotus, Dragon: The Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection at Asia Society (2020) is fully illustrated (though the picture quality is a little disappointing), with entries on each work featured in the exhibition. For me, the most valuable part of the catalogue is an introductory essay titled “Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd, Their Advisor Sherman E. Lee, and the Arts of Asia.” It features discussions of the Rockefellers and their backgrounds, their goals as collectors, and their relationship with Sherman E. Lee (1918-2008), their renowned primary advisor. During his tenure as director of the Cleveland Museum of Art (1958-1983), Lee transformed the museum’s collection into one of international importance.

Written for the general reader, the catalogue section follows the essay. Unfortunately this section does not contain footnotes, provenance information, or the dates when the Rockefellers acquired these works.

John D. Rockefeller 3rd (1906–1978) and Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller (1909–1992) in conversation with works in their collection, reception area of John’s office at Rockefeller Plaza, c. 1968. Photo source: Kimbell Art Museum Facebook.

Proser emphasizes a characterization Lee made about the Rockefellers — that they were concerned with “the human scale of the collection, preferring smaller, choicer groupings of works to an indigestible mass display.” He says they also wanted works that could be “understood and enjoyed by the interested layman.”

The catalogue addresses some questions I had about how the Rockefellers interacted with Lee, as well as their plans for the ultimate disposition of the collection.

Both John D. and Blanchette were actively involved in seeking out works for the collection, with visits to dealers in New York, Tokyo, London, Paris, and other cities. They undertook these gallery visits individually, as a couple, and in the company of Lee. The Rockefellers also continued to consult other dealers and advisors. Lee met periodically with the Rockefellers at their Beekman Place apartment to discuss how to refine the collection through subtraction as well as addition.

Today it would be considered unethical for a museum director or curator to work this closely with a collector who was not directly affiliated with that expert’s museum. These were more freewheeling days. Moreover, few museums, and only a handful of private collectors, were actively collecting Asian art on a major scale during this period.

Proser substantiated the rumor that Lee and Rockefeller would flip a coin if they both wanted an artwork that they had spotted at the same time. Confirmation came in the form of a Rockefeller diary entry pertaining to a 1974 auction. At the same time, one can see from the collections they built that Lee and the Rockefellers sometimes had very different priorities and areas of emphasis. In the area of Indian art, for instance, Lee acquired a staggering collection of Kushan era sculptures, from both Gandhara and Mathura. The Handbook of the Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection (1981), by contrast, lists only three Kushan era works. On the other hand, the Rockefellers built a remarkable collection of Chola era bronze sculptures, while Lee did not. At the time of the collection’s donation to the Asia Society, only Norton Simon and the Pan-Asian collection had a better group of Chola bronzes in the U.S. Speaking of his most prized bronze statue of Shiva Nataraja, Simon declared to the New York Times in 1973: “Hell, yes, it was smuggled… I spent between $15‐million and $16‐million over the last two years on Asian art, and most of it was smuggled.” Unlike Simon, the Rockefellers never knowingly bought smuggled works.

Over the decades, collecting opportunities varied greatly. The founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 led to the sale of many private collections, but the U.S. embargo on China prevented their importation from 1950 until 1972. As choice Chinese and Japanese works became rarer and more expensive in the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S.-Vietnam War (which was also carried out in Cambodia and Laos) led to a more plentiful supply of works from South and Southeast Asia. The Rockefellers’ pace of acquisitions declined in the mid-1970s as prices continued to rise. John D. Rockefeller’s death in a car accident in 1978 put an end to the couple’s collecting activities.

In Merchants and Masterpieces (rev. ed. 1989), Calvin Tomkins wrote that the Rockefeller collection seemed to be “pointed toward the Metropolitan” until the 1960s, when the museum deaccessioned some monumental Chinese sculptures and reaccessioned them with the Sackler name affixed to them (this was financed by Arthur M. Sackler, who was not one of the opioid Sacklers); thereafter, “Rockefeller distanced himself from the museum.” Sackler also financed the gallery in which they were situated, which allowed them to be exhibited for the first time. Nonetheless, the Met ultimately also lost the Sackler’s Asian collection to the Smithsonian, who gave him his own museum.

The Rockefeller collection was first publicly displayed in 1970 at the Asia House Gallery in New York. Proser notes that the Rockefellers considered donating parts of the collection to various museums, but ultimately decided to keep it together. According to Lee, the Rockefellers wanted the collection to serve as “a source of understanding” for an American public. The Rockefellers had enjoyed the small, contemplative private collections they had visited in Japan, and they wanted a similar environment for their collection. They were instrumental in the creation of Asia Society, to which they bequeathed almost three hundred works of art. Selections from the collection have rotated in the Edward Larrabee Barnes-designed building on Park Avenue since 1981.

Works from China

Food Vessel (Gui), China, reportedly found in Shandong Province, Eastern Zhou period, c. 6th century BC, copper alloy, Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.103a, b. Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts.

The Rockefellers acquired this vessel at the sale of the Frederick M. Mayer collection at Christie’s in 1974. This was the sale that forced the documented coin toss (unfortunately, Proser does not name the victor nor the prize). Luckily, there were two nearly identical examples of this vessel, so Lee also got one for Cleveland.

The surface of this vessel is covered with impressive geometric patterns. The stylized dragons at either end serve as handles. When the upper half of the vessel is removed, it functions as a bowl when its crest is utilized as a base. Such vessels were created by making piece molds around a ceramic model. After assembly into a complete unit, molten bronze was poured into the finished mold.

Stem Cup, North China, Tang period, c. late 7th–early 8th century, silver with embossing, chasing, engraving, and microscopic traces of gilding, Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.118. Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts.

This tiny, beautiful, and elaborate silver cup was made for some unknown elite, probably in one of the major Tang-period craft centers. After the cup was hammered, embossed, and chased, it was soldered onto a separately manufactured stem. Trade with central Asia and Iran during the Tang dynasty led to a profusion of luxury objects fashioned out of precious metals. The technique of chasing the tiny circles, known as ring matting, has Sasanian and Sogdian sources, which Chinese metalworkers brought to astonishing, meticulous perfection, sometimes with a profusion of birds and flowers, as in this example. See the Freer/Sackler website for Judith Lerner’s discussion of Sogdian metalworking and its influence on Chinese works.

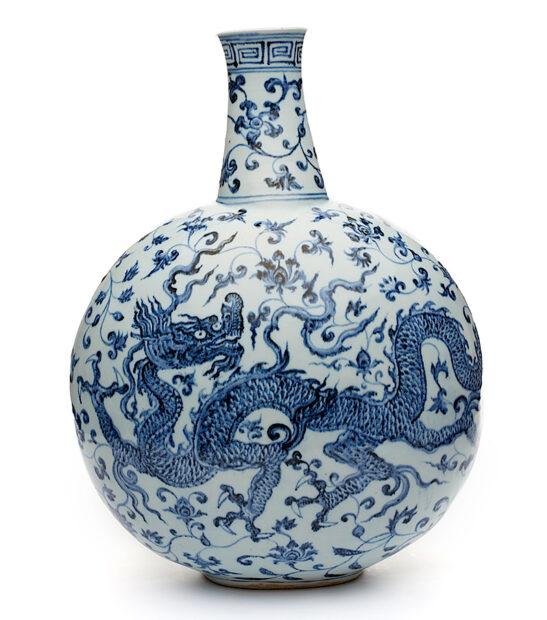

Flask, China, Jiangxi Province, Ming period, early 15th century (probably Yongle era, 1403–24), porcelain painted with underglaze cobalt blue (Jingdezhen ware), Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.160. Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts.

A bold and vigorous dragon extends across each side of this large flask, framed by a continuous frieze of lotus vines. Their proportionately massive heads, thin, snakelike bodies, large scales, and deep blue “clumpy” color are characteristic of the early Ming period. In China, dragons were regarded as benevolent and were associated with emperors. Dragons with three or four claws appeared on objects that Ming emperors bestowed as gifts. Given its size — more than eighteen inches — this flask could have served as an important diplomatic gift. Ming blue-and-white porcelain is particularly well represented in Buddha, Shiva, Lotus, Dragon. For the evolution of Ming blue-and-white ceramics, see this British Museum video. Two blue-and-white, early Ming period ceramics from the Kimbell’s permanent collection are also on view in the Kahn building. (An audio discussion of these two works is linked here.)

Bodhisattva Torso, probably Shanxi province, China, Tang dynasty (A.D. 618–907), c. A.D. 775–800, stone, traces of gesso and pigment, 39 x 12 15/16 x 8 in. (99 x 32.8 x 20.3 cm), Kimbell Art Museum.

The Rockefellers favored small-scale Chinese works. This magnificent torso (on view in the Kahn building) illustrates another dimension of Chinese art. As the Kimbell Art Museum Guide (2013) notes, the Tang dynasty was a culminating point in Chinese Buddhist sculpture: indigenous traditions masterfully adapted to Indian influences, with statues both “voluptuous and tactile, their sumptuous garments carved to accentuate the contours of the body, with flowing scarves and clinging ropes of beads to emphasize its curves.” A bodhisattva was a being who postponed nirvana to help other humans achieve enlightenment.

Bodhisattva Torso reflects Gupta period (321-500) sculptures from India, which were particular influential models for other Asian cultures. Tang sculptures, in turn, were influential exports to East Asia.

Works from India/Pakistan

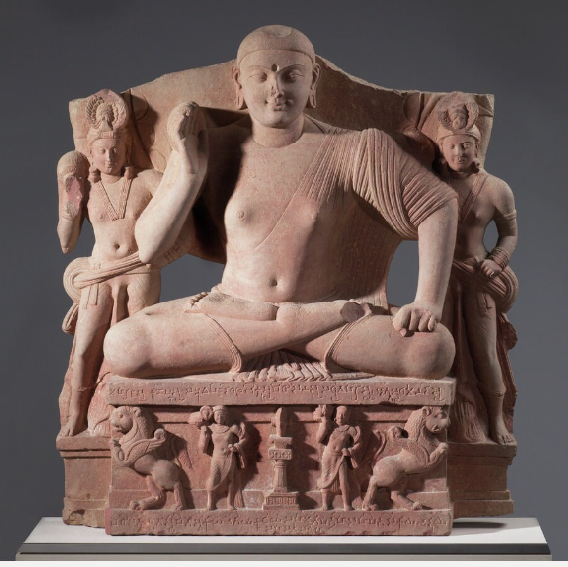

Buddha with Two Attendants, India, A.D. 82, Kushan period (c. 50 B.C.–A.D. 320), red sandstone, 36 5/8 x 33 5/8 x 6 5/16 in. (93 x 85.4 x 16 cm), Kimbell Art Museum.

At its height, the Kushan empire — which held strategic mountain passes on the silk route to China as well as key south Arabian ports — extended across parts of present-day Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan (Gandhara) and northern India. It had two capitals, Purushapura (near the Khyber Pass) and Mathura (between Delhi and Agra), and it generated two important sculptural styles. The Gandharan tradition is deeply influenced by western classical art, and its statues are carved out of gray schist; the Mathura school emerged from indigenous Indian traditions and its sculptures are hewn from mottled red sandstone.

The Buddha had not initially been depicted in human form. Instead, worship was focused on relics in shrines called stupas. The Kushans developed the now-familiar iconography of Buddhas and bodhisattvas in human form.

This superb and remarkably preserved Buddha is a prime early example of the Mathura style. Dressed as a monk, he is seated on a throne in a yogi’s pose as he personifies Shakyamuni, the teacher. His body is smooth because it is conceptualized as a container for the sacred breath. His thin, diaphanous robe clings tightly to his body, in some places almost becoming a second skin. In contrast, the many hulking, muscular Buddhas produced in Gandhara seemingly channel Hercules and Apollo — with curly hair and sometimes with an Apollo-like topknot as well — and are garbed in heavy layers of cloth. An imposing example of this type was acquired by the Kimbell in 1997. (Though it is not currently on view, it can be viewed here.)

This sandstone Buddha makes the gesture of reassurance with his right hand — a gesture that resounds through the history of Asian sculpture.

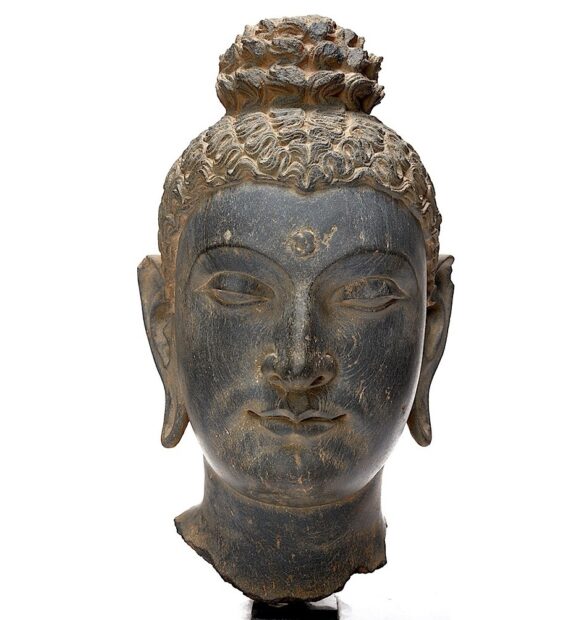

Head of Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara area, Kushan period, late 2nd–early 3rd century, schistose phyllite, Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.2. Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts.

Gandhara, which consisted of parts of present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, was one of the ultimate melting pots and crossroads of civilization. It had been ruled by Persians and by the Indian Maurya dynasty. It was conquered by Alexander the Great, and dominated and conquered by many others. Most importantly for the history of sculpture, it had become a tolerant, multi-ethnic society that produced extremely eclectic works. (I treat two classically-themed Gandharan trays in my Glasstire article “Cupid’s Revenge 2: Apollo and Daphne, From Ancient Greece to Airbrushed Fantasy.”)

The Indo-Greek successors of Alexander contributed Hellenistic influences. Whether they maintained a continuous influence, or whether classical influences came primarily from the Roman Empire — their major trading partner — is a lively matter of debate. See Wannaporn Rienjang and Peter Stewart, eds., The Gobal Connections of Gandharan Art (2019). In any case, Gandharan reliefs freely mixed classical and Buddhist subject matter. Within Gandharan sculpture, there is a large spectrum of classical influence, and this head is an example of relatively moderate influence.

Stanislaw Czuma makes several perceptive observations about this particular head in the exhibition catalogue Kushan Sculpture: Images from Early India (1985). He calls it a “perfect compromise between physical beauty and spiritual content.” Czuma points out that the individual features of the face conform to Gandharan types, yet they “all display rare beauty.” While the Gandharan sculptures that are the most classicizing emphasize bulk and physical power, the artist who created this head has other priorities. Czuma notes: “the heavy-lidded, half-open eyes and the expression of meditative concentration convey a meaning that goes far beyond the triviality of physical attraction.” He rightly connects this head to heads made from stucco, whose “more pliant material allows a ‘softer’ treatment.”

This head is a fragment of a complete figure. A nearly complete statue with a head similar to this one, but with more classicizing features, was acquired by the Kimbell in 1967 and is on view in the Kahn building.

It is the “softer,” more moderate classicism evident in works like this head that served to influence later sculptural traditions in India, from which it was transmitted to other parts of Asia.

Buddha, India (probably Bihar), Gupta period, late 6th century, copper alloy, 27 × 10 ³/4 × 7 in. (68.6 × 27.3 × 17.8 cm), Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.8. Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts.

The Gupta period (4th to 6th centuries) is viewed by many specialists as the most refined period of Indian art, when some of the currents we have seen were blended into a perfect synthesis. Influential artistic formulas were codified and disseminated during Gupta reign.

Steven Kossak gives this summary:

“…the Gupta period is characterized by suave, sensual, and refined images with flowing volumes. Artists strove to convey the inner spirit. The standard of beauty derived from literary metaphors. Thus, the Buddha (fig. 15) has a head like an egg, eyes like fish, lips like lotus petals, and a chin like a mango stone. His robe stems from Gandharan models, but the folds have been reduced to a stringlike surface pattern, a style typical of Mathura, which continued to be an important artistic center. The treatment of the robe serves to dematerialize both the cloth and the body beneath and therefore to convey the insubstantiality of the world as viewed by Buddhists. The aesthetic solutions reached in this type of image had enormous impact on the Buddhist art of Asia” (The Arts of South and Southeast Asia, issue of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 1994).

The Asia Society’s Buddha makes the fear-allaying gesture. Note his webbed fingers, and how the flattened robe resembles the webbing between his fingers.

In the catalogue, Proser notes the influence of this Buddha on other works in the exhibition from the Pala period in India, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

Shiva as Lord of the Dance (Shiva Nataraja), India, Tamil Nadu, Chola period, c. 970, copper alloy, Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.20. Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts.

The Rockefellers donated a dozen exquisite Chola bronzes to the Asia Society, none more important that this early Shiva Nataraja. The fiery areole that surrounds the dancing Shiva, which can be interpreted as the cosmos, gradually evolved to became round and fully encapsulating, as in another Shiva Nataraja from the Rockefeller collection that is dated to the 12th century (not in the exhibition). Ananda K. Coomaraswamy wrote that Shiva’s dance “became in time the clearest image of the activity of God which any art or religion can boast of” (The Dance of Shiva, 1924).

In Shiva Nataraja’s cosmic dance, the god is simultaneously creator, preserver, and destroyer. As Martin Lerner observes:

“If one had to select a single icon to represent the extraordinarily rich and complex cultural heritage of India, the Shiva Nataraja might well be the most remunerative candidate. It is such a brilliant iconographic invention that it comes as close to being a summation of the genius of the Indian people as any single icon can” (Recent Acquisitions: A Selection, 1986-87, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987).

Detail of Shiva Nataraja, “Buddha, Shiva, Lotus, Dragon: The Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection at Asia Society” installation, Robert LaPrelle, Kimbell Art Museum.

The god’s frenzied dance causes his braided and jeweled locks to fly from both sides of his head. The sound of creation had emanated from the small drum in Shiva’s raised right hand. His upper left hand holds the antithetical power — the fire of destruction. Shiva’s lower right hand makes the fear allaying gesture. His right foot tramples the personification of illusion. Shiva’s lower left hand points to his left foot, which is upraised to provide refuge. Thus Shiva offers salvation from illusion and from the endless cycles of creation and destruction.

Nepal

Standing Buddha Shakyamuni, Nepalese, 7th century A.D., Licchavi period (A.D. 400-750), gilded copper, 19 3/4 x 8 x 3 3/8 in. (50.2 x 20.3 x 8.6 cm). Kimbell Art Museum.

This gilded representation of the historical Buddha (on view in the Kahn building) is a prime example of how closely Nepalese sculptures followed Gupta prototypes. Iconographically, the right hand is extended in a gesture of charity.

Cambodia

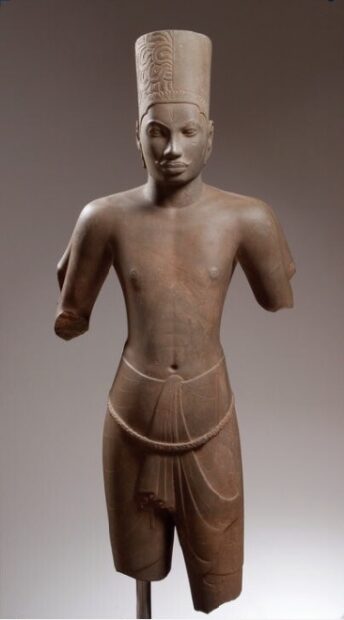

Harihara, Cambodian (pre-Khmer), c. A.D. 675–700, Pre-Angkor period (A.D. 550–802), Stone, 45 1/2 x 20 7/8 x 11 in. (115.6 x 53 x 28 cm). Kimbell Art Museum.

Harihara is a composite god, divided down the middle. This example (on view in the Kahn building) shares the same body and costume. Only the head is differentiated. The right half is Shiva (identifiable by his matted hair and half of the vertical third eye carved on his forehead); the left half is Vishnu (identifiable by his tall hat).

In the Shiva Nataraja, Shiva took on all the powers and functions of the gods. In Hindu iconography, Vishnu is normally recognized as the preserver of the world. At the end of each cyclic age, Vishnu goes into a deep sleep, and Brahma, the creator, is born from a lotus that rises from his navel. Thus, in this image, we can regard Shiva as the force of destruction, held in tension with Vishnu, the preserver who births Brahma, the creator.

This statue is both vigorous and austere, with characteristically smooth forms and tight-fitting garb.

Shiva, Cambodia, Angkor period, Baphuon style, 11th century, sandstone, Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.64. Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts.

The third eye in the forehead of this Angkor period statue identifies it as Shiva. Some may say it is an imposter, but Proser uses a better term: it is a “convert.” The somewhat clumsy carving of that third eye marks it as a later addition. Moreover, in the top center of this figure’s headpiece, a small figure or form has been effaced. This now-erased form was an image of Buddha or a stupa, which is a Buddhist reliquary shrine.

Shiva (detail of upper half), Cambodia, Angkor period, Baphuon style, 11th century, sandstone, Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.64. Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts.

Therefore, this statue was originally Buddhist — it was probably a four-armed bodhisattva. This underscores the fungibility of gods within a given period in Cambodia. Here a single emblem is enough to make a Hindu god out of a Buddhist image. A Hindu ruler could “convert” a Buddhist image — and even a major temple complex — made by a predecessor into a Hindu one, and vice-versa. While Angkor Wat had Hindu origins, the powerful king Jayavarman VII was Buddhist. His successor Jayavarman VIII reinstated Hinduism, but Buddhism won out as the dominant religion. For a brief treatment, see Ashley M. Richter’s blog “Recycling Monuments: The Hinduism/Buddhism Switch at Angkor” (2009).

Korea

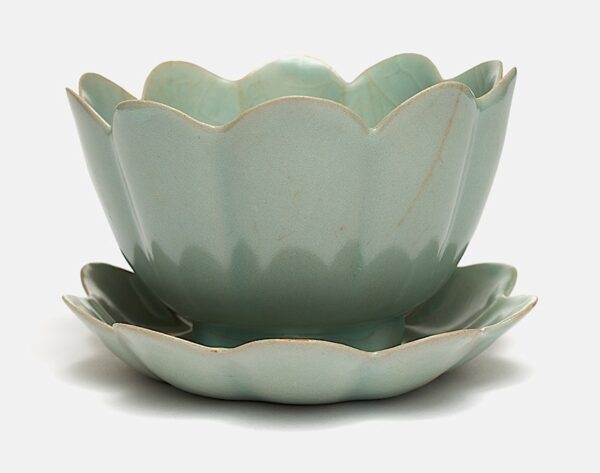

Foliate Bowl, Korea, South Cholla Province, Koryo period, early 12th century, stoneware with glaze, Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.193.1. Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts.

Buddha, Shiva, Lotus, Dragon features a pair of bowls and saucers with the famed “celadon” glaze that brought international attention to Korea’s Goryeo dynasty (918-1392) stoneware. It was so esteemed that a 12th century Chinese writer referred to the “secret color” as “first under Heaven,” because it was unequaled, though much-imitated. Proser says these dishes could have been used for delicacies at court banquets.

Nonomura Ninsei (Japanese, active c. 1646–94), Tea Leaf Jar, Edo period, 1670s, stoneware painted with overglaze enamels and silver (Kyoto ware), Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.251. Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts.

In reproduction, this tea leaf jar is one of the most unprepossessing objects acquired by the Rockefellers. Nonetheless, it was Sherman E. Lee’s favorite object in the collection. Moreover, it was designated an Important Cultural Property in Japan, which meant that it was banned from export. Nonetheless, John D. made an appeal and won. (When making requests of this type, it helps to be a Rockefeller.)

Ninsei set up a shop near an important temple in Kyoto in the mid-17th century, where he became close to Kawamori Sowa, an important tea master, who used his wares in formal tea ceremonies. Ninsei utilized precious materials for this jar. He used silver to highlight the wings of the mynah birds, as well as gold in the bottom center, near the bird’s tail in the above illustration. This work can only really be appreciated in person. It was made as an object of gradual disclosure, to be savored in-the-round by a person who would enjoy the way the narrative unfolds. On the other side of the jar, the mynah birds fly to the center where a pair are either brawling or playing.

Proser thinks this vessel was probably made as a luxury object for contemplation, though it has the shape of a functional tea leaf jar, including the lugs at the top that are used to fasten the lid. Lee, who admired Ninsei, had included a photograph of another tea leaf jar by the artist in his survey book A History of Far Eastern Art (1964).

Drum-Shaped Pillow, Japan, Saga Prefecture, Edo period, late 18th–early 19th century, porcelain painted with overglaze enamels and gold (Arita ware, Imari style), Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.233. Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts.

As noted by Proser, advanced ceramic technology came to Japan via 16th century invasions of Korea. In the 17th century, unrest in China nearly ended porcelain exports. These factors contributed to Arita’s global primacy in porcelain production, for domestic use as well as export.

This ceramic pillow was made for domestic consumption. In Japan, they kept elaborate hairdos from getting mussed, but they never caught on in the West. White cherry blossoms stand out against the red background that is characteristic of the Amari style.

Price points out that the 36 East Asian ceramics showcase the technical and artistic innovations of Chinese porcelains produced over a 400-year period, and also “demonstrate how Korea and Japan took inspiration from China, but also created ceramics that were uniquely their own.”

I have discussed only a few of the treasures in Buddha, Shiva, Lotus, Dragon. Given the Asia Society’s bustling exhibition program at its New York headquarters, it is not often that this many great works are on view, even in New York. Therefore, this is a great opportunity to see highlights from this esteemed collection, which can be readily supplemented by highlights from the Kimbell’s own remarkable collection of Asian art.

On view though Sept. 5 at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth.