Standing within the F. Marie Hall Special Projects Gallery of Midland’s Museum of the Southwest, the viewer may be forgiven for considering Sara Drescher’s new work, at first glance, to be comforting and benign. One is surrounded by watercolor paintings of crockery, after all, each rendered with reassuringly naturalistic exactitude. The repeated subject is recognizable — we know these objects: the ubiquitous casserole dish that many of us grew up with, white and decorated with cornflower-blue blossoms or, alternatively, a red-green-gold bounty of vegetables. In our shared memories, we associate these covered dishes with home, nurturing motherhood, and church potlucks organized by womenfolk. They are benevolent, nonthreatening forms … right?

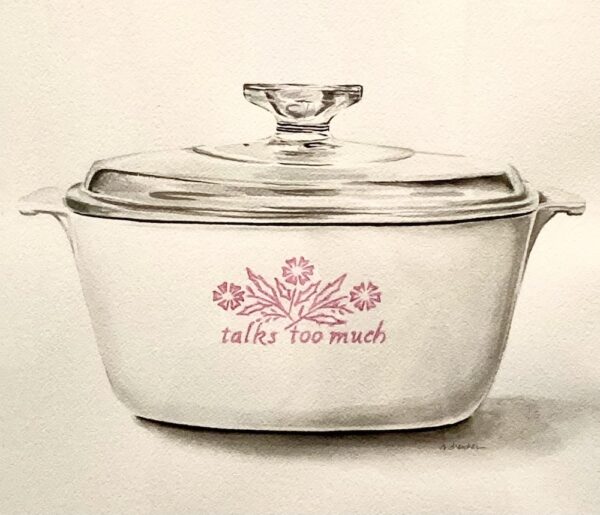

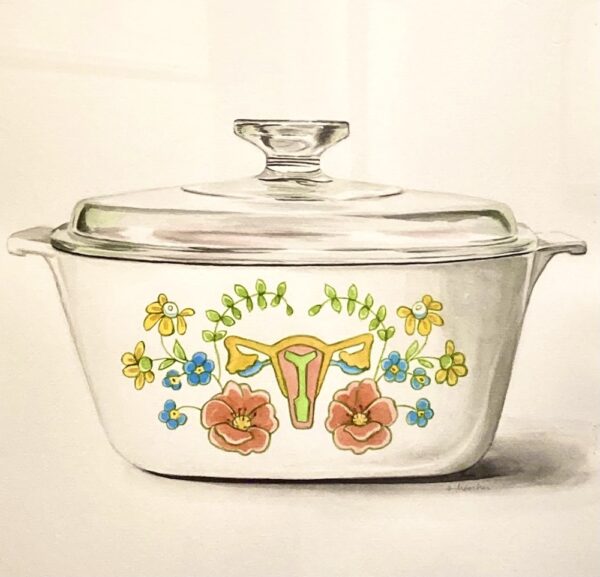

It is only upon closer inspection that we see Drescher has weaponized her Corning Ware (well, the title of the exhibit, Reclaiming the Casserole, is a clue, too). With seemingly innocuous tweaks, she imbues these objects with materiality, transforming them into metaphors for the female body (which is itself often clichéd as a vessel) and for the hackneyed-but-pervasive stereotypes of female roles.

In her series of “paper casserole” assemblages, the casseroles are bound, gift-like, in messaged wrapping. From each of these containers rises a plush fabric form — Bread Winner and Airhead are two examples — that evoke rising bread dough, out-of-control, and bring to mind the I Love Lucy episode in which a phallic loaf of bread bursts from the oven, aiming itself for Lucille Ball’s pelvis.

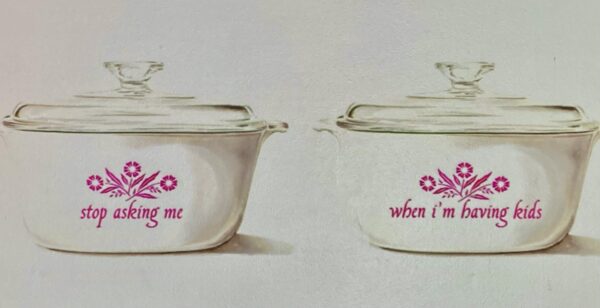

Projected on one wall of the gallery are twin images of painted casserole dishes, inscribed with captioning, the impactful brevity of which recall Barbara Kruger’s word-banners and Jenny Holzer’s truisms. In these, the vessel on the left remains static (i.e., don’t assume), while the right-hand casserole progresses through a continuation of the phrase (i.e., i’m not leading … i’m not the expert … i can cook). The silence of the work, the slow fade of one image into another, and even the lower-case letters and the diminution of the “I,” come off as self-effacing, nonaggressive. Paradoxically, the provocation lies in these very features, as well as in the insistent quality of the repetition itself, and the obdurate stasis of the casserole form. The captions, too, are compelling in that they tap into women’s shared experiences.

As the projection scrolled to “stop asking me … when i’m having kids,” it immediately brought to my mind my own encounters, particularly one: Some years ago, I was at a class reunion when I was accosted by a classmate who was only a slight acquaintance, someone with whom I’d probably had a total of two or three conversations in my life (though none at all in our school days) and whom I had not seen in years.

“I’ve always wondered,” she began almost immediately, “was your not having kids a decision, or were you guys not able to?”

I was stunned; but before I could collect a response, she gushed, by way of explanation for her curiosity, “Because my kids are everything to me. I can’t imagine my life without them.” With that pronouncement, the situation had gone from bad to worse: If it was our choice not to procreate, then we were selfish, incapable of bestowing love as she had; if we were unable to have children, then we were pitiable. Either way, the implication was that I must be unfulfilled.

The thing is, I don’t believe this person’s intention was to insult; but Drescher’s work points to the several ostensibly “harmless” messages that women receive every day about who and how they are expected to be. Individually, these exchanges seem mild; cumulatively, they are destructive. In her statement on the series, Drescher points out that the societal expectations foisted upon women “can be frustrating, and a burden if a woman’s life path is not the ‘default.’” Then she adds:

Even in the 21st century, many women wonder if they are “ok” or doing enough, whether they fit the traditional roles and molds, or decide to break out of tradition and pursue another purpose. These internal questions can be as painful and damaging as external questions and assumptions from other people.

By addressing these issues of shame associated with not meeting perceived standards, it is Drescher’s hope that, one day, such questions — internal or external to women — will become irrelevant, that her work will prove confusing to a future society. For today, though, the meaning rings all too true.

Through Oct. 31 at Museum of the Southwest, Midland