Something happened in the last year. Without indoor gatherings, the streets became the de facto social space. The shift wasn’t even, however. Shutting down business meant shutting down a reason to go anywhere. The cross-pollination of neighborhoods and the through-flow of North Texas stopped. The chance encounters with friends and acquaintances stopped, and it seemed that going out or staying in yielded the same result: no familiar faces to be found.

People filled the streets during this time, to be sure. People walked their dogs morning, noon, and night. People brought Champagne to the park and laughed on their terraces. There were people, it seemed, who could weather the storm and wait at home, with each other. For them, waiting for normal may have felt like a family staycation.

Under normal circumstances, I would not be alone so much of the time. I would be visiting artist friends, in their studios or at their receptions, catching up on all the ways they have found their own pathways to creating over these months. Hearing their stories enriches the viewing experience, but it’s also comforting. Artists often live in ways that seem unconventional, or inventive, which, while I sheltered in place, I realized to be rare. I was bound to my neighborhood. Looking out my window toward my neighbors, I started to see differences that I hadn’t noticed before.

In this time, I’ve encountered three literary works by contemporary artists that offer a surrogate experience: Autofictional stories of life under the creative impulse.

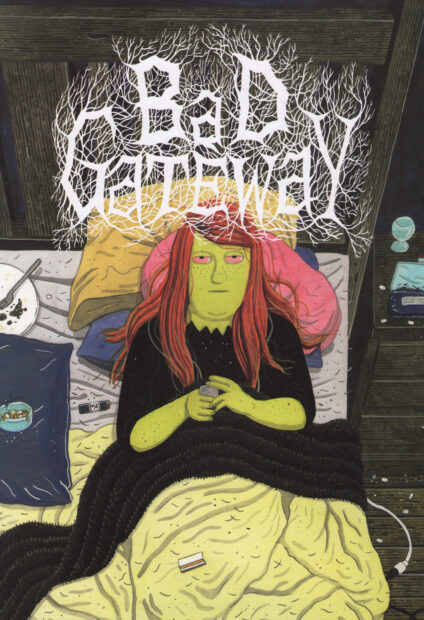

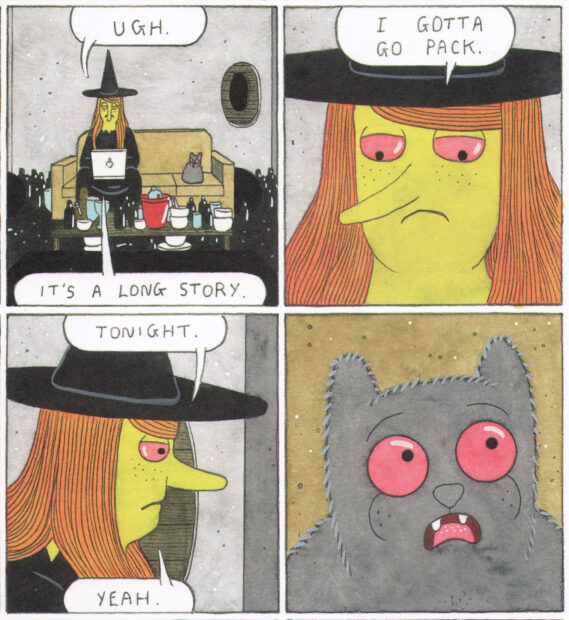

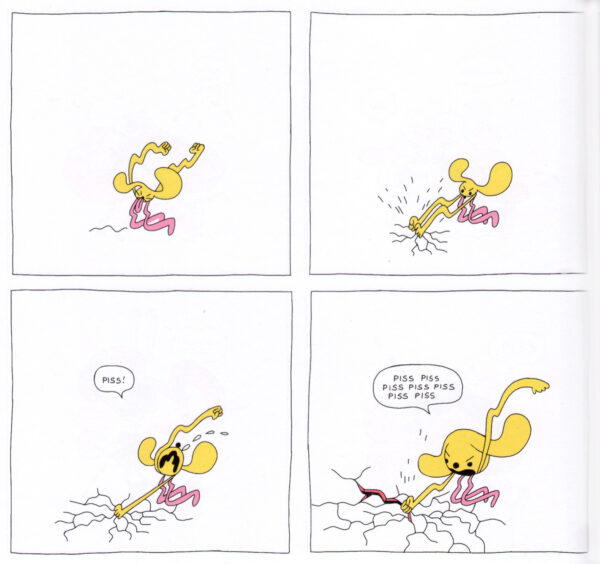

Simon Hanselmann’s Bad Gateway is a continuation of the artist’s popular Megg, Mogg & Owl series, in which a witch and her cat boyfriend waltz through life one day at a time. Hanselmann uses humanity to endear us to these degenerates, but doesn’t pad out with pleasantries the banality of underachieving. These people make bad decisions in broad daylight, loudly.

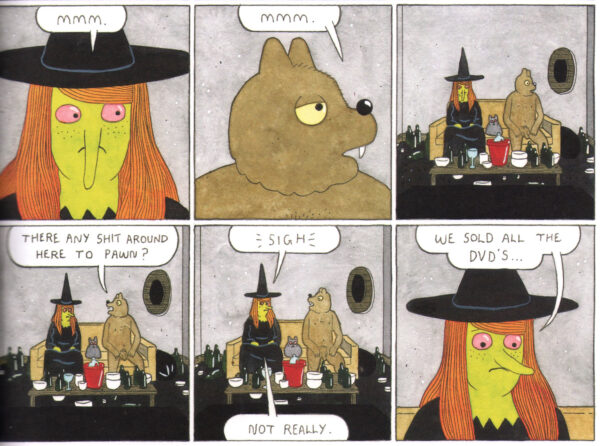

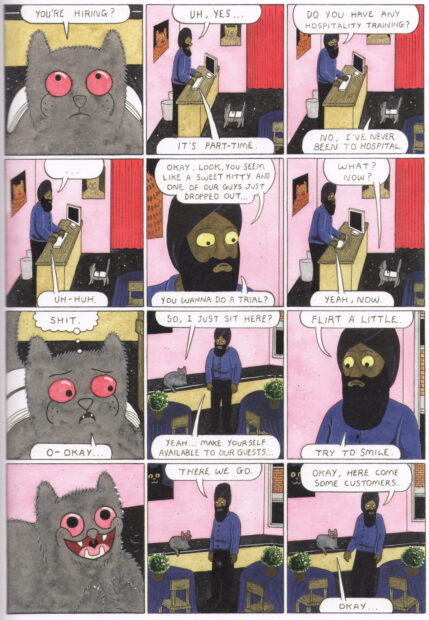

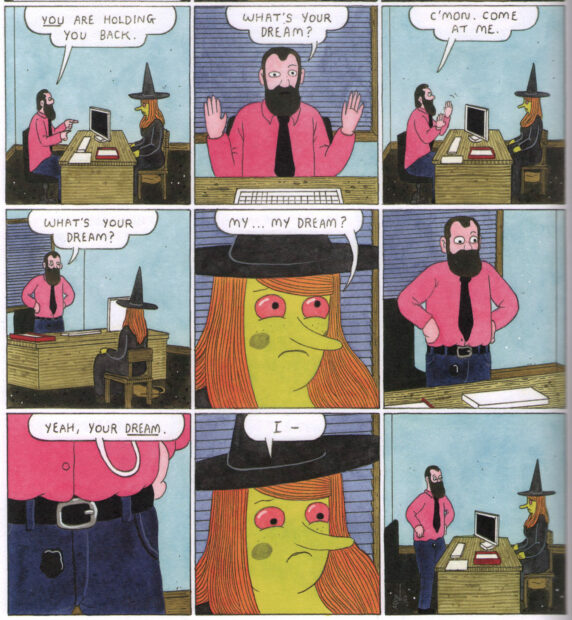

Megg and her roommates are short on rent, in part because they buy too much weed and, more importantly, because they avoid working. Megg makes a desperate plea to the welfare office to continue her financial assistance from the state, and later, the crew try to sell a pair of roller skates so they can score one night’s share of drugs for the three of them. At every stage, they stumble to make even the most meager gains, and their collective failure strains the friendship. They are unwilling to compromise their lifestyle for any semblance of normalcy — even when it comes to making rent on their modest hovel, which is lined with wine bottles and beer cans.

Megg, the titular witch, has green skin which beams glamorously from the flat world of Bad Gateway. Mogg, her boyfriend, is a talking cat who is unhireable, adding to the impending rent crisis. Werewolf Jones, a local friend, hangs around between benders, pushing the boundary of how much hedonism is too much for the group. Megg encounters her own needs through the demanding situations that friends put her through, and eventually is summoned home. On the flight to answer her mother’s call, we can feel that this does not portend a respite from the chaos that troubles Megg.

Hanselmann has spoken about how comics were an essential outlet of his life growing up in remote Tasmania. Daniel Clowes has called Haneselmann’s work “the real deal,” and once wrote: “I actually find his comics really depressing and thank God that I don’t ever have to hang out with anybody like that ever again.” In other words, Hanselmann is capable of telling these stories: of the abject and the noncompliant. They’re endearing in the sense that they are relatable. In Bad Gateway, a bottle is not a symbol of an evening of well-spent relaxation. Sometimes, the bottle is the problem as much as it is a fact of life.

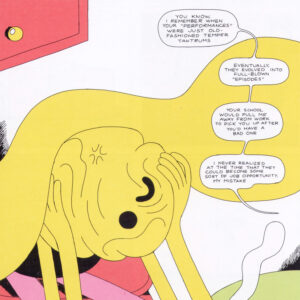

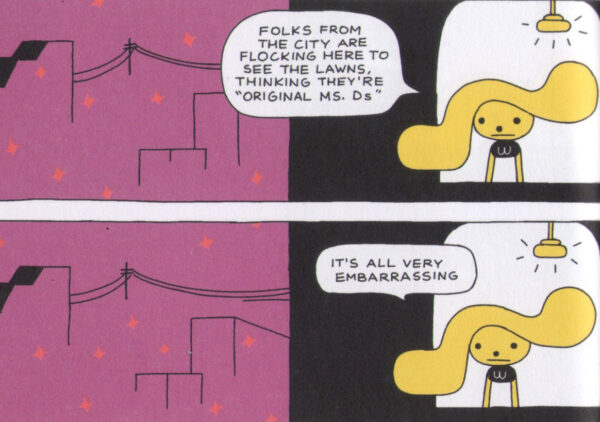

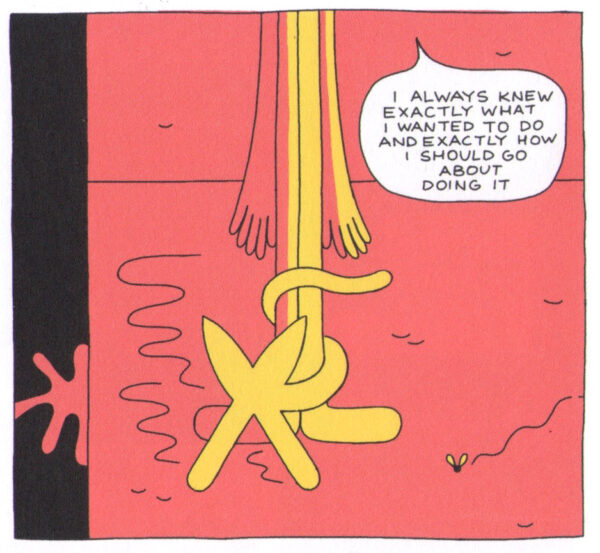

In Brat, Ms. D is a stretchy provocateur; she’s famous for “delinquence,” an art form that she has singlehandedly elevated into popular consciousness. Michael Deforge’s worlds are occupied by the silliest ordinance of people who don’t act as if they are living in a cartoon world, which brings the slapstick antics down to Earth in the unlikeliest of ways. The main character here is a universally lauded artist, even if her art form is subject to the pitfalls of celebrity. Ms. D has no authentic relationships, and she’s too singularly revered to have peers. She lives as a myth, so famous that her own identity has lost all of its roots.

Ms. D pontificates toward the reader in various passages about how unfulfilling it is to be adored. Her type of artwork, call it social practice or public performance, has been adopted so wholeheartedly by the mainstream that she has become incapable of topping her own antics. All of her relationships are cynical. In a late-stage panel, Ms. D’s intern, Citrus, expresses her ambivalence about being accepted to her preferred college, and asks her mentor if she has an opinion. Citrus has taken an oath of compliance for D’s heinous acts — quite the investment for an uncompensated position. The devoted Citrus is looking for direction, and the emotionless Ms. D defers the decision back onto Citrus. Do what you want. A pregnant future.

Brontez Purnell’s Since I Laid My Burden Down follows DeShawn, an Oakland punk who originally hails from Alabama. Before DeShawn can reflect on his time in California, he is called home for a family funeral. Purnell has said that he writes from an autofictional space.

DeShawn’s account of gay life, from Alabama to California, is remarkably absent of cynicism. Circumstances roll through the narrator’s perspective, and he doesn’t hold his tongue. There is a sense that Purnell is passing on elder knowledge as he is learning it himself. The author has an ability to render reality while passing earnest assessments:

“DeShawn was dubious as to how Michael kept the store open, particularly a bookstore selling anarchist ideas in a city where capitalism was winning more and more every day.”

This is the perspective from which Purnell describes the world, and his role within it. His observational wit is more welcome when spoken to us through an unrelated third party. When DeShawn returns to the South to participate in the mourning rituals of his family, he’s confronted with the aspects of rural life that he abandoned as a teenager. There are trysts with locals — boys he attended school with over a decade ago — who must be tip-toed around during errand trips and at church gatherings. The narrative beats of the novel imply an avoidant relationship model that underpins all of DeShawn’s relationships. This is not lost on DeShawn, because the factors that determine his relationships often feel outside of his choosing.

DeShawn spends a lot of time narrating the foundational people in his life that he’s seeing once again. He’s no longer a child or dependent on family. He recounts their faults and mortality, partly as generational knowledge, and partly as gossip, and we learn how these people accept and acknowledge DeShawn’s place outside of the social order.

As an artist and an iconoclast, DeShawn has the freedom to come and go, to live his own way. His self-reflection is, in fact, the sign of a life lived on one’s own terms.

1 comment

In what literary universe is Bad Gateway an autofiction? I love Hanselmann’s comics, and they are well-worth examining, but talking owls, cats and werewolves place this in a different genre than autofiction in my view.