Installation view of On Screen / Off Screen Contemporary Painting and Technology: Kate Petley, Lorraine Tady, & Liz Trosper. June 5 – July 31, 2021. Images via Barry Whistler Gallery, Dallas.

Nominally this is a show of abstract paintings, but the three artists — Kate Petley, Lorraine Tady, and Liz Trosper — seem to be striving to make non-abstractions and non-paintings. A stretched canvas is, of course, a convention, like a stage set. A hundred years ago it was seen as a window; increasingly it’s a metaphor for a screen because that’s what most people look at all day. In the show the artists silently debate, through their painted proxies, how much to reveal of the guts and wiring of this perceptual frame.

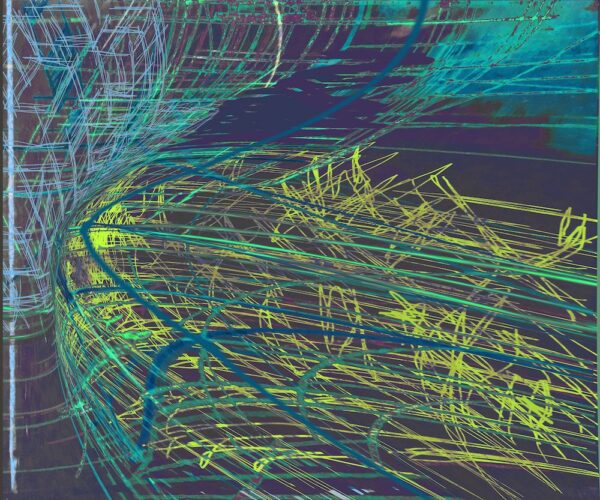

For Lorraine Tady, the “screen” represents a snapshot of messy, convoluted, un-photographic processes. Tasty line quality, complex color, Cezanne-ian push and pull, and implied three-dimensional depth left over from the “window” era of painting still need to be present, even if there are no actual paint drips or signs of active layering or erasure on the surface. All that studio chaos remains essential, even if it’s ultimately flattened into a jet of ink uniformly sprayed onto a canvas.

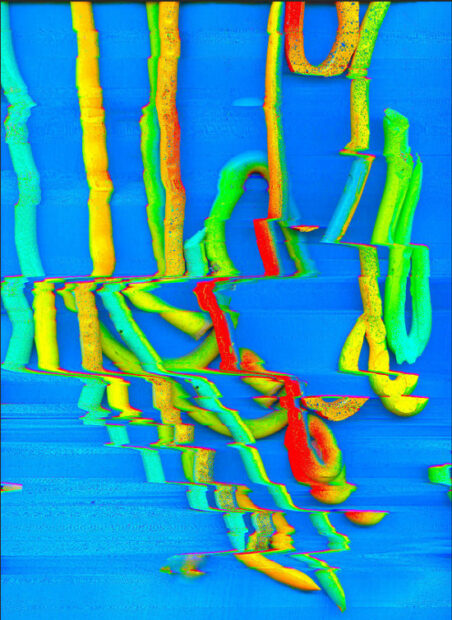

Liz Trosper doesn’t emphasize the artist-skilled hand but believes hand manipulation still plays a role in art. Hers “perform,” like a puppeteer’s, moving ropes of brightly colored extruded acrylic around on a flatbed scanner. The movements, slow or jerky, confuse the scanner, creating accidental patterns and moires similar to analog TV static. This allows the machine itself to “perform,” with random gesture-like strokes that confuse and flatten the images of meandering tubes of color. As with Tady’s work, this activity reaches a final stage — a photographic rendering printed on canvas — without any further mark-making.

For Kate Petley, some hint of physical paint must be present on the surface in order to pull the viewer’s eye into the frame, even if only, initially, to satisfy curiosity about what is actually brushed or sprayed or taped. Once lured, the attention remains fixed on the imagery and other puzzles emerge. For example: What are the shapes in her paintings, exactly? They appear to be elegantly folded corrugated cardboard, casting dark, photographic shadows. It’s not photography in the flat, scanner sense but is shot in a “tabletop studio” style, with tripod, camera, and lighting documenting temporarily set-up materials. Glimpses of the crumpled models are lost in seductive fields of pure color, which might be paint on the canvas, paint on the photographed object, or the reflection of colored gel lights hitting planar surfaces.

But printing processes and imaging technology have improved so much nowadays that the eye has great difficulty discerning what’s painted and what’s printed, which may be why the presence of paint is less of an issue for the other two artists. Petley’s photographs are digitized and printed on canvas but she stresses in her artist’s statement that the photos are “created in-camera, not in the computer” and that it’s “urgent” for her hand-painting to be present in the finished print (albeit subtly blended with the photography). Clearly she draws her personal ethical line at the completely printed painting and use of software interventions in the digital conversion from photo to canvas.

But is old-school photography, with its rich textures and shadows and indexical relationship to the Real, automatically superior to sculptural maquettes imaged in the harsh light of a scanner bed? Is the play of incandescent light and shadows inherently more honest than virtual lighting and filter effects in Photoshop, which can be used to achieve similar ends?

Ultimately it’s a conversation and not a jury trial. All three artists are asking the kinds of questions everyone should be asking about our brave new Screen World. How much of the “media landscape” is manipulated? What are acceptable levels of manipulation? What is the role of aesthetics in modern life? Can visual seduction be good or must it always be challenged? Is photography truth? Can deep fakes be detected? Is the artist a shamanic figure attracting followers with overt physical talent, or a behind-the-scenes game player whose work must be decoded? It’s a lot to ask of one exhibition, but all that interrogation is there if you give it a hard look.

Through July 31 at Barry Whistler Gallery, Dallas.

Tom Moody is an artist who has been blogging since 2001. His website is https://tommoody.us