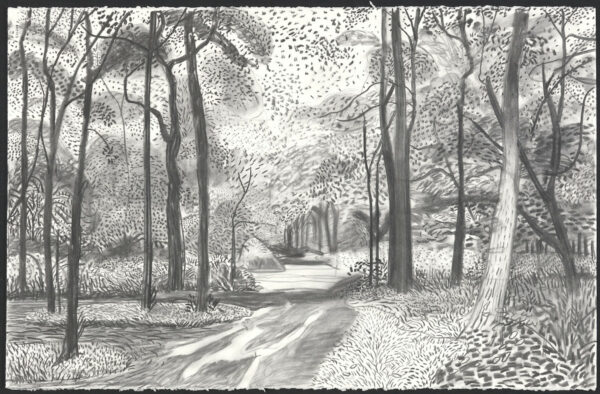

David Hockney, Woldgate Vista, 27 July 2005. Oil on canvas. 24 x 36″ © David Hockney. Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt

A single blade of grass might not matter much to the average person, but for Vincent Van Gogh, it was the key to an entire world. “This blade of grass leads [a man] to draw all the plants, then the seasons, [and] the broad features of landscape,” he writes to his brother Theo in 1888. More than a century later, English artist David Hockney seems to agree. In a 2019 video, he explains, “When you’re drawing one blade of grass, you’re looking, and then you see the other blades of grass, and you’re always seeing more.”

Hockney – Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston is a luminous, timely exploration of how both artists find the sublime in the close observation of nature. Curated by Ann Dumas, the exhibition marks the first time that Hockney and Van Gogh have been paired in an American museum. The Joy of Nature features 47 of Hockney’s large oil paintings, graceful watercolors, delicate charcoal works, vibrant iPad drawings, and experimental videos from the past 20 years, along with 10 of Van Gogh’s lesser-known paintings and drawings.

Rather than tracing a simple story of artistic influence — Hockney was first introduced to Van Gogh’s work on a school field trip as a boy — The Joy of Nature highlights the surprising overlaps in the men’s biographies and artistic approaches while still leaving each artist room to breathe. The result is that walking through the exhibition feels like listening to an intimate, unfolding dialogue between Hockney and Van Gogh about what led each of them, in their own way, to devotedly depict and interpret nature in their artworks time and time again.

“Although they’re separate in time and come from different parts of the world, there are many parallels,” Dumas says on a recent video call. Hockney grew up in the industrial city of Bradford, England in the 1950s; Van Gogh was born in the Netherlands a century earlier. As adults, both artists fled their drab, northern European homelands in search of the strong light and bright colors of warmer climates. Hockney went to California, and Van Gogh moved to southern France.

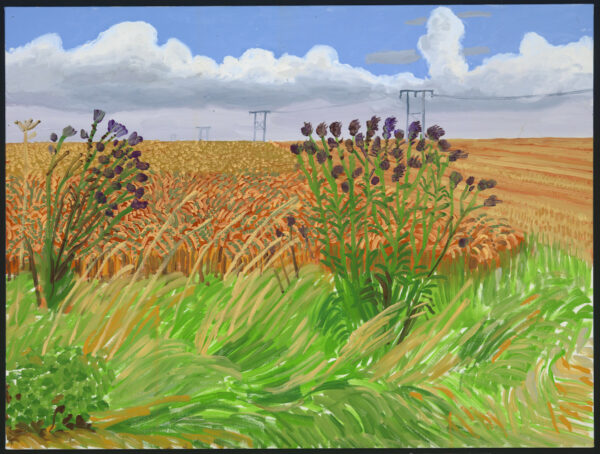

David Hockney, Wheat Field off Woldgate, 2005, oil on canvas, collection of the artist. © David Hockney / photo: Richard Schmidt

At 83 years old, Hockney has lived a significantly longer life than his Dutch counterpart, who died at age 37, and the years have given the English artist the chance to reexamine his roots. Hockney returned to his native region of Yorkshire in the early 2000s to care for his aging mother and an ailing friend. There, he saw the familiar surroundings with fresh eyes, and began a years-long mission to record the nearby farms, fields, villages, and forests in his art.

By then, landscape painting had been considered so passe for so long by the mainstream artworld that Hockney’s project amounted to a revolutionary gesture. “Hockney swam against the tides of fashion in art in the second half of the 20th century,” Dumas notes. Unlike so many avant garde adherents, “His art has always remained absolutely rooted in what you can see in the natural world. For him, that’s the idea of artistic truthfulness.”

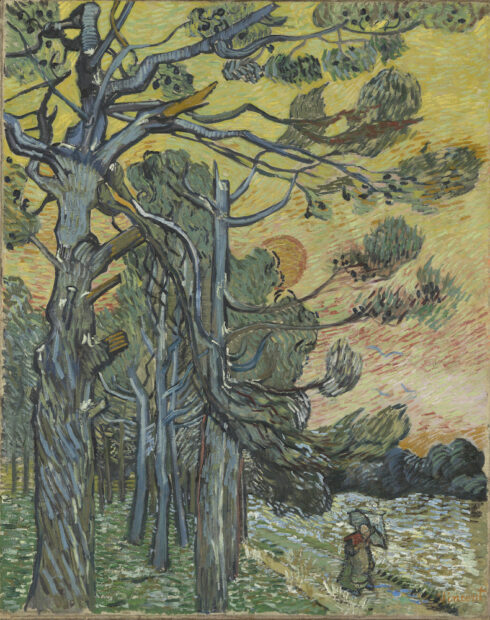

In The Joy of Nature, truthfulness is not just a faithfulness to nature’s image, but to its impact on the spirit. Hockney and Van Gogh are tireless chroniclers of the world around them. Everything from a swaying flower to the arrival of spring is captured by Hockney’s skillful smudges and shades, and Van Gogh’s swirling dots and dashes. Both artists are also great colorists. While a patient at the asylum at Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh writes reverently of “the superb effects of pale citron skies”; they appear in his ethereal painting Pine Trees at Sunset (1889). Hockney’s glowing colors practically vibrate off the wall, but his observational works often feel true enough to awaken the senses. In radiant works like Early June Tunnel (2006), we almost hear the wind rustle the leaves, feel the heat of midday on our skin, and smell the dusty earth.

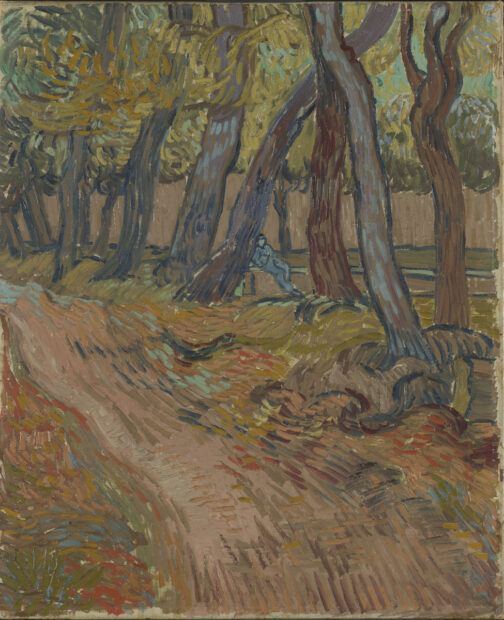

Both artists insist on working outdoors, aided by new technologies like paint in tubes for Van Gogh and the ever-portable iPad for Hockney. But nature doesn’t just appear in the artists’ depictions; it’s embedded in the materials and surfaces themselves. We learn, for example, that while out in the field, Van Gogh battled with the fierce “mistral” wind of southern France, and would often draw with a pen he’d fashion from nearby reeds. Hockney also paints and draws on the spot. His 2006 Woldgate Woods paintings were made — despite their massive scale — en plein air and through all four seasons. The various stages of finish in his Midsummer: East Yorkshire (2004) watercolor series suggest sudden turns of weather; one is even splashed with raindrops. Through sun and snow, Hockney and Van Gogh work in and from nature. It’s a beautiful but physical task, and the challenge of making art in this way seems to open up a kind of transcendence for the artists.

David Hockney, Woldgate, 26–27 June 2012, charcoal on paper, collection of the David Hockney Foundation. © David Hockney / photo: Richard Schmidt

“They both have worked out means of conveying the beauties of the natural world with a great directness that really touches people in a very immediate way,” Dumas explains. Hockney and Van Gogh are endlessly fascinated by nature, and, through their art, they share that passion with a sincerity, intensity, and emotion that draws audiences in. “Their profound response to nature and the capacity to use their art to really convey a kind of individual and deeply felt response to nature has immense universal appeal,” says Dumas.

Hockney and Van Gogh’s dedication to drawing nature requires a different kind of sight and different pace than what we’re used to today. Their vision chooses to be deeper, slower, and more meditative than daily looking. It’s a stance that feels even more resonant during the pandemic, when we’ve all been forced to slow down. And after so much time indoors, immersing oneself in the greenery of The Joy of Nature is certainly a welcome balm.

On view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston through June 20, 2021.