For the past decade and some change, Alicia Eggert has placed language at the center of her sculpture practice, usually taking the form of signage, which tries to account for the materiality of its content. She has a Derridean streak of thinking, hinging on the ways presence and absence of signifier and signified make meanings visible or felt by a body in space/time. But Eggert’s pieces are much more fun than Derrida, their puns less tedious. Her current show’s title, Conditions of Possibility, is vague and jargony compared to the work on view, which is at times funny, poetic, direct, and conceptually elegant. This is the Liliana Bloch Gallery’s first solo showing of the Denton-based artist, though her neon and kinetic installations have been widely exhibited in the region and beyond.

Alicia Eggert, Between Now and Then, 2008. Custom engraved corridor sign. 2” x 2 1/2” x 8.5”. Photos courtesy Liliana Bloch Gallery

The draw here is some new in-the-flesh work, as well as novel documentation and miniature mockups of previous and future projects. One large piece looms in the open space while others hang from the large white walls, half-pretending to be functional elements of the building itself. For instance, an early work, Between now and then (2008), greets us from overhead as we enter the unmarked gallery, like a small, lone hallway sign from a hospital wing or government building. Rather than telling us where we are, it tries to point us to when we are. The words “NOW” and “THEN” are engraved on either side of a faux-woodgrain placard, with official brass hardware fixing it above our heads. It’s a simple toggle trick — the two signs fused back-to-back leverage the physical impossibility of our viewing both at once, with our inability to simultaneously conceive of both referents.

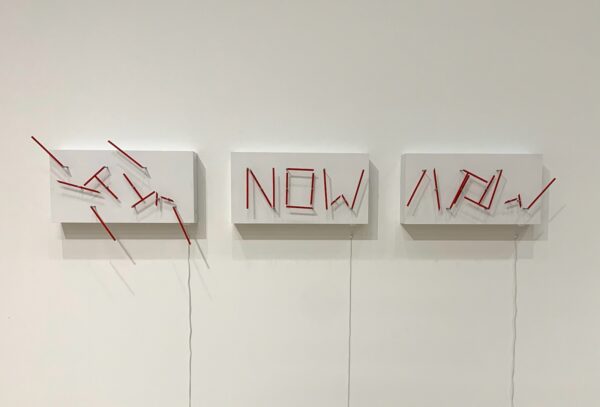

Alicia Eggert, Small Nows, 2020-21. DC motor, gears, aluminum, wood, paint, electrical wiring. 17 1/2” x 25” 6”. Fabricated by Duoc Le

Temporal conundrums aplenty here: the piece Small Nows is a trio of identical kinetic sculptures that pack the guts and extra red hands of clocks into shoebox-sized housings, with matching white electrical cords leading down the wall to daisy-chained power strips. There is a considered aesthetic that refuses to conceal those details, which I appreciate. Spinning vectors chug around like Wonka-meters, coming together every so often to form the word NOW — a flash of recognition that quickly returns to its mechanical ballet. It’s another great trick, making the text feel perishable, visually analogous to speech. Meanwhile, the vectors move on to accidentally form crooked Ts, Ks, maybe an N, but mostly grinding away to the motor-noises that aurally structure the even, mechanical time between “NOWs”.

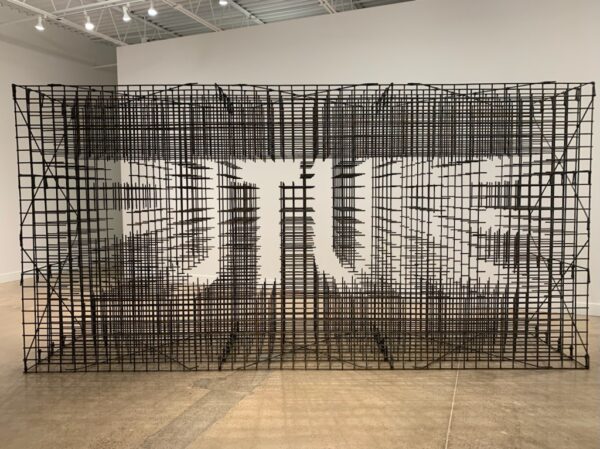

The two largest works in the room face off aesthetically and point in opposing directions, out from the present moment we’ve been trying to locate. One to the unbuilt future, the other to the nostalgic past.

The Unimaginable Future is a freestanding, billboard-sized construction built of six layers of rebar panel wired together in a rectangular grid, with blocky segments hacked out to create letters from negative spaces. The piece is so large you would need to back up into the parking lot to clearly read the word “FUTURE” gaping within it. Instead, parts of the word trip into view as you move past, fractured like a repeating mirror reflection. Your eye gets to climb through the scaffolding and enter the porous object, an unfinished stretch of highway maybe, some unbuilt infrastructure, who knows? The piece has a beautiful economy of material — like a spoken word, it’s mostly air.

Alicia Eggert, Alas, 2021. Fresh cut flowers, chicken wire, MDF, paint, 36” x 84” x 6.” Flower arrangement by Penny Halcyon

Alas retorts from a nearby wall, offering a near total contrast. Lush arrangements of cut flowers are zip-tied onto a painted-white MDF template of lowercase cursive script. The baroque exclamation references the past, regret, the inability to change something. On the day I visited, the bundles of flora were crinkling, drooping, petals falling to the floor: daisies, roses, chrysanthemums, in pinks, maroons, yellows and dirty whites. The object itself seemed to sigh in a slow-motion wilt, its meaning enacted over days and weeks.

Like artist Jenny Holzer, Eggert’s works seems to start with a rumination on the content of language and collaborates with other artisans’ hands to help build the texts into different scales and materialities, uttering their mantras at varying speeds, volumes, inflections, and through different avenues of the body. Unlike Holzer though, whose phrases often hurl past us, Eggert circles around and around, with an interest in getting behind the signifier. Where Holzer’s texts hide incompatible logics made superficially compatible by their uniform quality as text, Eggert’s phrases come off as earnest and circular, trying to pry open their referent.

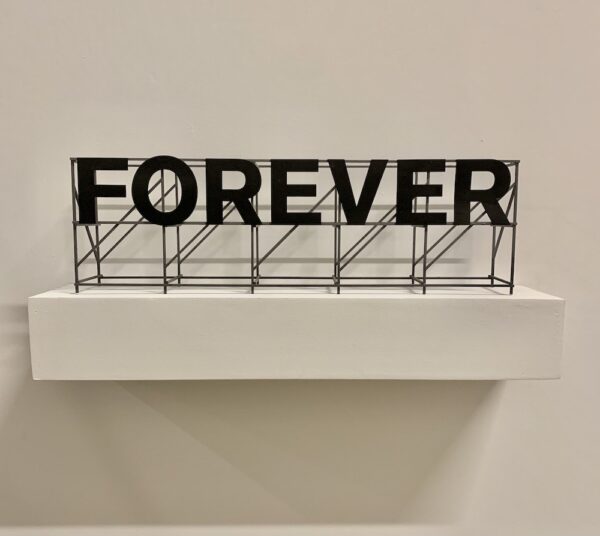

Sprinkled around the reception area and stashed in the backroom are some delicious drawings and small-scale models, as well as a few holographic photographs that cleverly document flashing neon installations from Eggert’s previous projects. They further complicate their own relationship with time, though something about their adjacence to the work they document gives them clarity. Fittingly, these before and after the (arti)fact objects position us viewers between a recorded past and an imagined future.

We all think so uncritically these days about how “the word” (logos) manipulates us, shapes our ideas of where, when, and who we are. The ways communication is forged into objects and transacted; written, spoken, recorded, played back, transcribed, live, synchronous, etc., has never been more convoluted or rich, depending on how you look at it. Eggert’s work doesn’t quite clear things up for us, but it does give us space and a script to begin asking our own questions.

Through May 22 at Liliana Bloch Gallary, Dallas.