More than 750,000 design patents have been issued by the United States Patent Office since 1900. Although patents are traditionally used to demarcate intellectual property and design ownership, they’re also an archival means of tracing people and ideas through history. Architectural designer Thomas Rinaldi found exploring historical patents to be a way of unpacking how innovation follows certain trends and design impetuses over time.

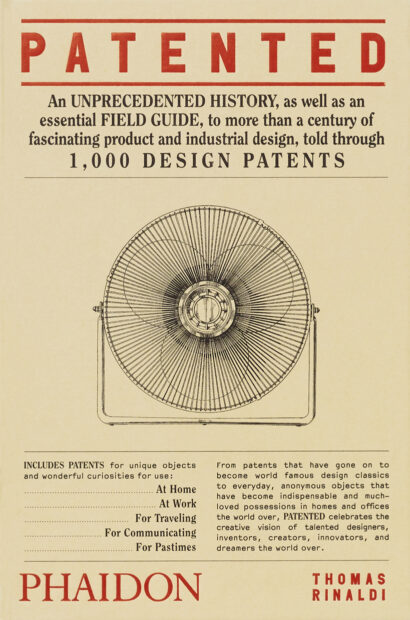

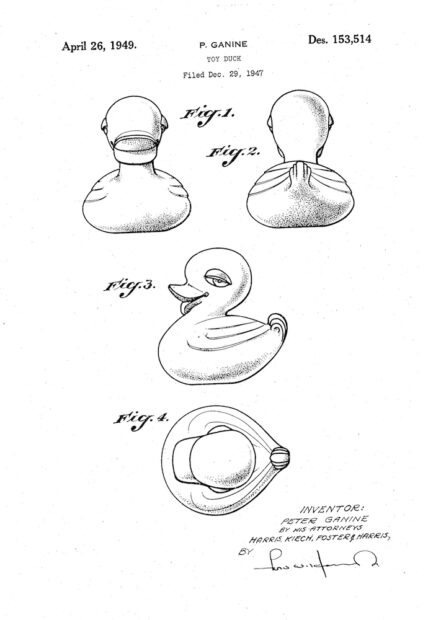

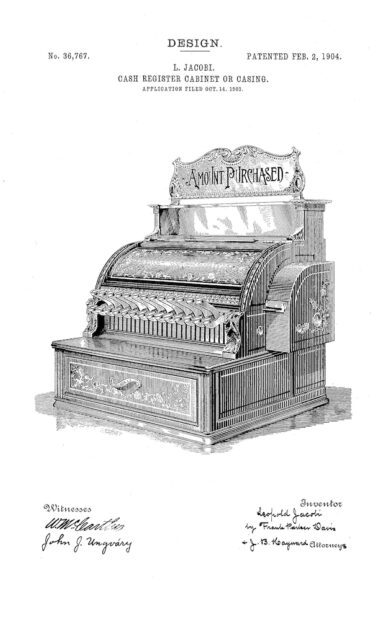

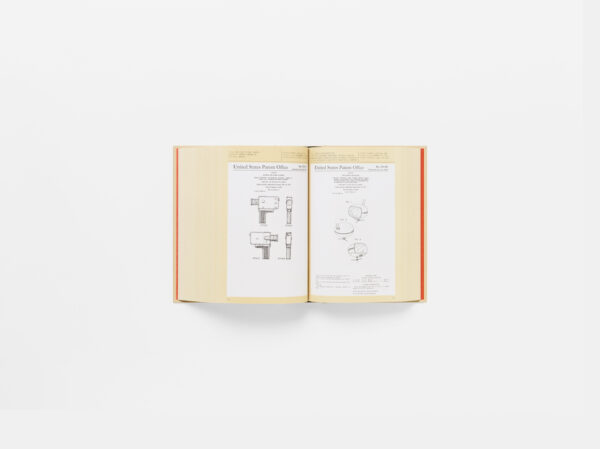

Patented: 1,000 Design Patents is a collection of one thousand patents from 1900 to today, drawn from the archives of the United States Patent Office. Rinaldi’s collection highlights a patent’s illustration page from the application; the page contains a black and white, line-drawn illustration (even for the twenty-first century patents), the patent number, the date that the patent was granted, and the name of the designer (“inventor” in patent parlance.) The one thousand patents that are included are a mere “one-one-thousandth of the pool from which they were selected,” as Rinaldi describes. “Capping the list at one thousand therefore made the selection process something of a grueling undertaking.”

Casing, Leopold Jacobi, for the National Cash Register Company, 1903-1904. Patent Number: USD 36,767, U.S. Patent Office (page 44)

In Patented, Rinaldi highlights patents filed by many big names in product design – Jacobson, Dreyfuss, and Eames – as well as people outside of the world of design proper, like Donatella Versace, Francis Ford Coppola, and even Elon Musk. (The collection includes a 2013 patent illustration for a Tesla sedan.) Rinaldi’s selection of patents fundamentally focuses on industrial design rather than fashion or graphic design; the emphasis on industrial design patents allows readers to dive into the historical twinning of form and function for a plethora of everyday objects. The magnitude of humankind’s material culture is undeniable.

In biology, an evolutionary tree is a way of illustrating branching events and ancestor-descendent relationships between organisms. It’s a helpful way to see the introduction of new characteristics and to see how groups of organisms change in size, shape, and adaptions over time. The first sets of patented designs in Patented are organized around the same idea. Readers are presented with a two-page spread of the design illustrations for categories of objects and those categories — bathroom scale, alarm clock, washing machine, etc. — and the myriad ways that each object in a category can be designed and re-designed. This approach highlights how certain items are influenced together over time like an evolving organism.

Patented: 1,000 Design Patents, Thomas Rinaldi, Phaidon. Magnetic Tape Cassette, Reinhold M. Weiss & Michael Dennehey, for the Memorex Corporation, 1970/1972 (left), Chair, Thomas Lamb, 1970/1972 (right), pages 706-707

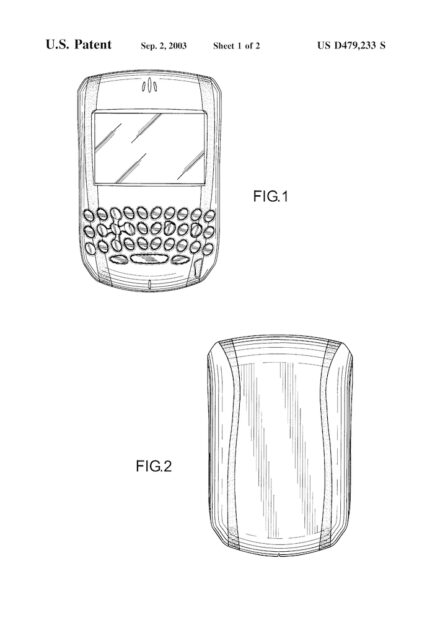

For example, the eighteen different irons (from 1900 to 2019) show that what makes an iron “an iron” is a handle, a flat surface, and a heat source — but the way that each of those characteristics is met varies greatly. The same holds true for the electric mixer, a plug-in floor fan, or a washing machine. But the “evolutionary tree” of cell phones shows how the object (thanks to other technological innovation) has been slimmed down and no longer requires an external antennae. The cultural and technological evolution of objects can be found in their patent designs. Where most of the patent designs from the early 1900s are recognizable — and, perhaps, even useable twelve decades later — more often than not, objects have a higher rate of cultural turnover.

Handheld Electronic Device, Jason T. Griffin, for Research in Motion, 2002/2003. Patent Number: USD 479,233, U.S. Patent Office (page 939)

The patents in the book that may strike a note for today’s readers are 1990s tech objects — things that are old enough to look outdated, but are recent enough to be found in the living memory of readers (“Oh, I had one of those”), and yet wouldn’t be found in vintage or antique stores. These are objects somewhere between “artifact” and “junk.” The clunky-looking digital camera (1997) featured in patent 386,775, for example, or the pocket-sized “organizer” with a stylus (1998) from patent design 397,679. Not all of the 1990s tech objects are completely extinct. The triangular “computer enclosure” with rounded corners filed by “Jobs et al” in 1998 and granted in 1999 made me smile; it was the original, iconic iMac case that still boasts a cult-like following today.

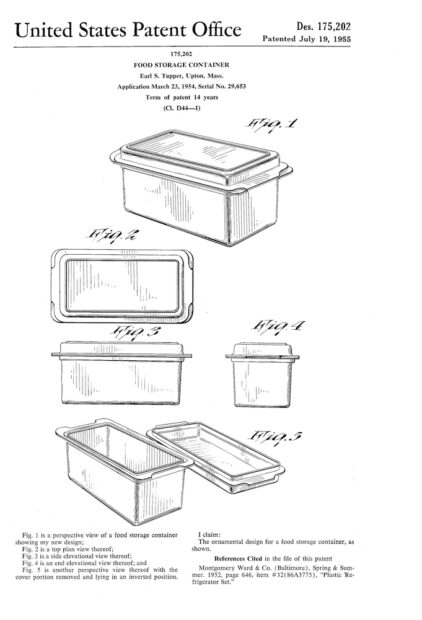

Food Storage Container, Earl S. Tupper, 1954/1955. Patent Number: USD 175,202, U.S. Patent Office (page 508)

With one thousand patents in this collection, it’s easy to find one’s focus drawn to famous names (Jobs, Versace, Musk, etc.). But what is most interesting are the patents Rinaldi chooses to show that are held by people who history has not remembered. The objects are identifiable, but the small twist that a designer added to an object’s “bauplan” — what makes alarm clock 41, 725 different from alarm clock 602,380 — demonstrate that objects are made and re-made over decades. The less-known inventors of toaster 203,527 from 1966, or bathroom scale 88,997 from 1933 (the names of which have been removed in Rinaldi’s composite figures at the beginning of Patented), serve as a reminder of which things stick around and how they’re often subject to outside social, cultural, and historical factors. As the United States Patent Office imposes no citizenship requirements for filing a patent, Patented features patents filed from designers all over the world — Taiwan, Korea, Spain, Italy, and the UK, to name a few, as well as the United States.

Patented is one-part exploration of an archive of documents; one-part history of design; and one-part social commentary. More than anything else, however, it’s a fascinating dive into the thinking about the design of things we use — and don’t! — today.

****

Released May 12, 2021. Find the book here.