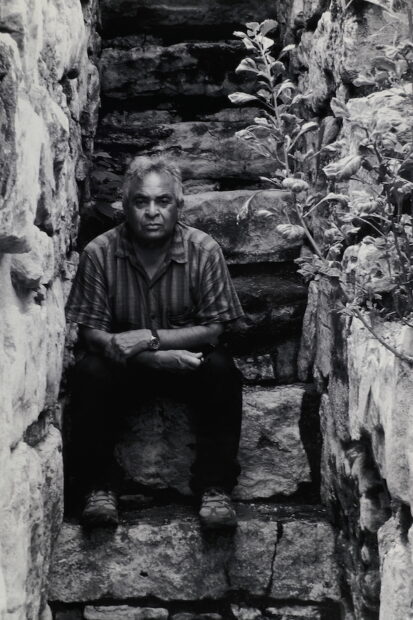

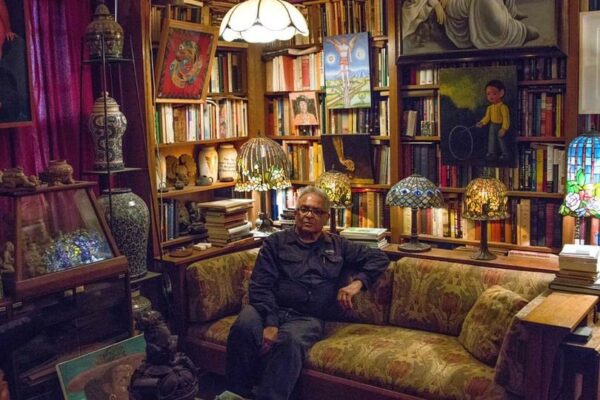

Gubidxa Guerrero Luis, Portrait of Juan Sandoval, Photograph on Paper, 29¾” x 19¾”. Mexic-Arte Museum Permanent Collection 2020.2.201.1. Gift of Juan Antonio Sandoval Jr. Courtesy the Mexic-Arte Museum

Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

For the majority of prominent art collectors, their ability to buy art can be traced back to an abundance of personal or familial wealth. For Mexican and Latinx art collector Juan Sandoval, it can be traced back to the simple decision to not own a car.

“He always said the money he might have spent buying an automobile, maintaining it and buying gasoline, he had that amount of money available to purchase art,” says Claudia Rivers, head of Special Collections at UT El Paso Libraries and a close friend of Sandoval’s.

Sandoval served as UTEP’s reference librarian and subject specialist for art and Chicanx studies for nearly 40 years. On a modest salary, Sandoval built a monumental collection over his lifetime, totaling more than 1,500 works, which he donated to the Mexic-Arte Museum in Austin before his passing in January 2021 at age 74 from a longtime illness. He also allowed Mexic-Arte to select books from his personal collection to add to the gift.

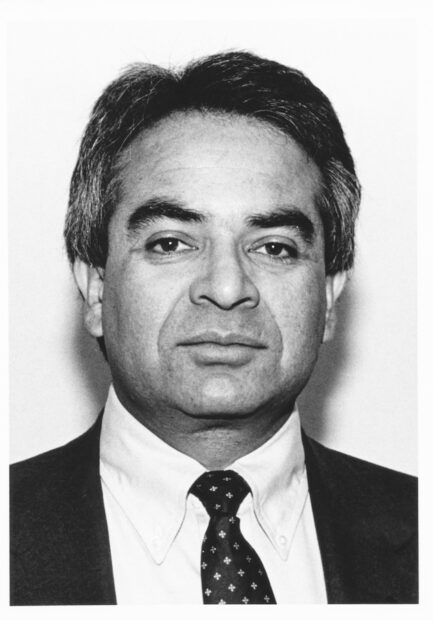

Juan Sandoval in 1991 when he won a service to students award at UT El Paso. Photo by Laura Trejo, UTEP Communications.

From humble origins, Sandoval was born ninth of eleven children in a rural community in Southern Colorado. “I think that goes to show that someone who has an interest and even a modest income can build an important collection of art,” says Rivers. “You wouldn’t think he would have a big background that would allow him to become an important art collector. But he built up the knowledge himself during his lifetime, and I think coming from a background like that is a very impressive achievement.”

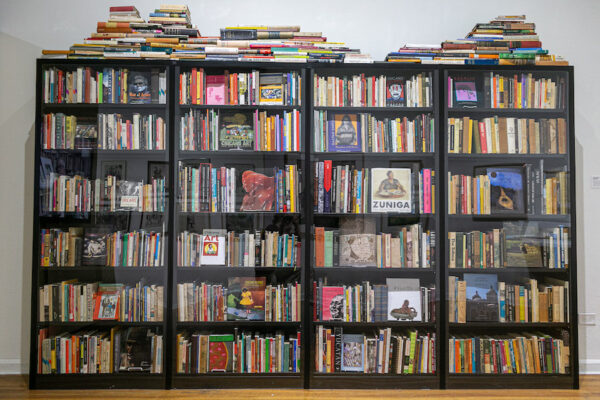

Installation view of Mexico, the Border and Beyond: Selections from the Juan Antonio Sandoval Jr. Collection at the Mexic-Arte Museum in Austin, Texas. Photo by Cody Bjornson.

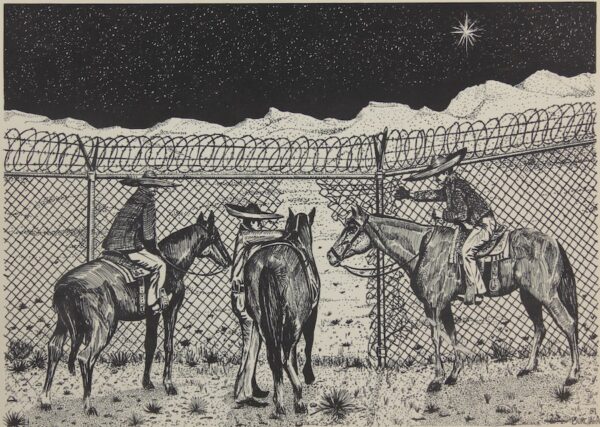

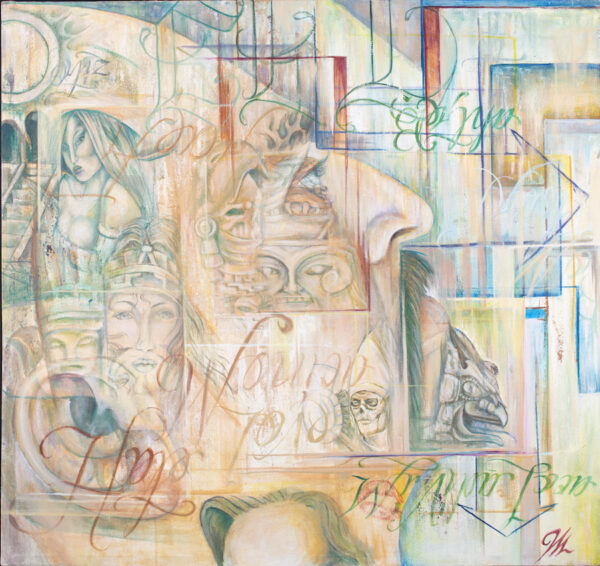

Sandoval primarily collected the work of Mexican and Latinx artists, including many works touching on themes of the border, immigration, economic inequality, Mexican American identity, the Chicano Movement, and much more. A selection of works — everything from handmade kites by Francisco Toledo to indigenous Oaxacan textiles — from Sandoval’s collection, titled Mexico, the Border and Beyond: Selections from the Juan Antonio Sandoval Jr. Collection, is currently on view at Mexic-Arte in Austin until August 22. The exhibit, organized by the museum’s Executive Director Sylvia Orozco and Curator Dr. George Vargas, offers a personal look into the life of the collector, and thoughtfully outlines themes of his collection around historical events.

“I think it is the greatest gift we have ever received,” says Orozco. “The art and books from Juan Sandoval.”

A section dedicated to Sandoval himself, complete with mock home library, tea sets and tricycles, introduces the show to visitors. A video of Sandoval speaking can be heard throughout the gallery, emphasizing his presence in the old building. Adjacent gallery rooms offer figurative drawings, papier-mâché folk figures, serigraphs, and paintings.

Installation view of Mexico, the Border and Beyond: Selections from the Juan Antonio Sandoval Jr. Collection at the Mexic-Arte Museum in Austin, Texas. Photo by Cody Bjornson.

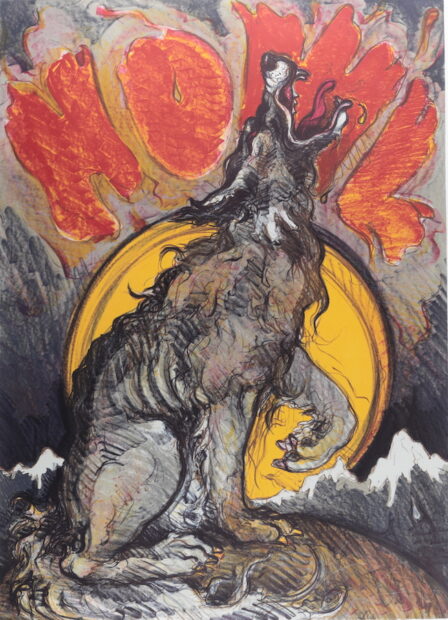

There seems to be no medium that Sandoval did not collect. The exhibit reflects Sandoval’s championing of artists from the border region and Mexico, celebrating the diversity of viewpoints and experiences among them. José Cisneros, Francisco Delgado, Carmen Lomas Garza, and Marta Arat are among the artists featured. 2D works by El Paso-born Luis Jiménez are prevalent in the exhibition and highlight his popular subjects of lowrider car culture, border crossing, and the formation of the American West. One wall places his Air, Earth, Fire, Water lithograph, a depiction of Aztec lovers Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl, next to Cholo Van with Popo and Ixta, which exemplifies Jiménez’s practice of expressing Mexican and Chicanx cultural heritage within an American context.

Sandoval went on record many times stating his collection was primarily a result of his desire to help artists make a living. He was fortunate to meet and acquire art by early-career artists who went on to become internationally recognized.

“I realized you could buy original work for very little, if you were in the right place at the right time. And it appears I’ve been in the right place at the right time most of my life,” says Sandoval in a video interview from 2014.

While this is the largest exhibition of Sandoval’s collection to date, his works have appeared in a show at the El Paso Museum of Art (EPMA), and institutions would often borrow work from Sandoval for exhibitions. He had connections all over the country, including at the Smithsonian, and was well-known in the Latinx art community.

Only 230 works of Sandoval’s 1,500 piece collection are currently on view in Austin. The Mexic-Arte staff is still accessioning the collection and conducting condition reports. The Sandoval exhibit was funded by a $100,000 CARES Act Grant from The National Endowment for the Humanities. Stipulations of the grant include retaining jobs at the museum, including humanities scholars in programming decisions, and making online resources available, all which Mexic-Arte has abided by.

Orozco first met Sandoval more than 20 years ago at the UTEP Library while she was working on a José Cisneros exhibition for Mexic-Arte. On that trip she visited Sandoval’s house and says she was impressed by his art and book collection. They kept in contact, and he participated in a panel on collecting Latinx art around the year 2000 at the museum. After that, the two drifted apart and weren’t in contact until December 2019, when Sandoval called to ask if he could donate his art collection.

“He nonchalantly, very casually said, ‘You know, I want to donate, I’ve decided I’d like to donate my collection to you if you’re interested.’ I was totally surprised,” says Orozco.

Orozco arranged to stop in El Paso to meet with Sandoval on her way home to Austin from Riodoso, New Mexico. By that time, Sandoval was in the hospital, so Rivers, a close friend of his, took Orozco by Sandoval’s home to see his collection, which Orozco says had doubled or tripled in size since she’d last seen it.

“I saw what it entailed, and the amount, not only of artwork, but of books. I’m a book collector too, and Mexic-Arte is a book collector, not only of informational books, but of rare books,” says Orozco. “That was an added benefit or discovery. He said, ‘You can take whatever you’d like.’”

Mexic-Arte has been in similar situations before. Orozco and a small team worked at the house for several days and preliminarily catalogued and packed items to bring back to Austin. Orozco personally went through all the books. She says her love of books and experience as a 7th grade library assistant, reading and organizing shelves, was welcome preparation for this overwhelming task. Sandoval had vast interests and collected in many different areas.

“He also did a good job in categorizing them within his home. He had all the cookbooks together, all the geography books together, all Pre-Columbian art together, English literature. It was a librarian’s library. Quite wonderful,” says Orozco.

She had to be scrupulous, only selecting books that had to do with history, culture, Mexican American and Latinx art. If Orozco came across duplicates, she’d take one and leave its twin. Sandoval donated the remaining books to El Paso independent bookstore, Brave Books.

“I’m glad they have gone to another wonderful home, because they were very valuable and very important books that needed to go somewhere that would honor them and understand what the gift was,” says Orozco.

Installation view of Mexico, the Border and Beyond: Selections from the Juan Antonio Sandoval Jr. Collection at the Mexic-Arte Museum in Austin, Texas. Photo by Cody Bjornson.

Sandoval requested the museum reproduce his library as part of the installation. Orozco says that while the museum may not have enough shelf space, they have included a selection of the books in the exhibition, to give the impression of how integral books were to Sandoval, both as art objects and as learning tools.

“I think they’re inseparable — the books are part of the collection, and part of the artwork. They go together because they strengthen each other. That’s how I feel that he felt,” says Orozco.

A significant number of the books added to the museum’s library from Sandoval’s collection are out of print or contain notable signatures and ephemera. The museum will utilize the books as reference materials, as many contain information on artists you can’t find on the internet. Mexic-Arte’s pre-existing library consists of specialized books Orozco brought back from Mexico. Orozco studied art at The University of Texas in the ‘70s and says library books were instrumental in her introduction to Mexican art. For those who may not frequent museums, like Orozco prior to her collegiate years, art books are an accessible vehicle for visual culture.

“I remember sitting on the floor for hours, in the stacks,” says Orozco. “I found the section of the Mexican muralists, and that’s where I discovered Modern Mexican art.”

Orozco says while recently there have been more Mexican American and Latinx books in circulation, in the past there’s been a lack of material. Rivers says books published in Latin America and Mexico have traditionally been hard to come by due to short print runs and a lack of centralized distribution.

Considering Sandoval’s regional focus on the border, El Paso originally seemed like the natural home for his collection. It would also have given the city a chance to boost its reputation as one worth visiting for its cultural offerings. Regrettably, due to a lack of government support for local arts and an unsettled debate about a highly-anticipated Mexican American Cultural Center, Sandoval was unable to leave his collection and his legacy to the city in which he built it.

Sandoval’s predicament is echoed by the contentious and ongoing debate in El Paso about the 2012 Quality of Life bond. The voter-approved bond, the largest ever passed in the city, allocated $228.2 million for signature projects, including a multipurpose arena, a children’s library, and a Mexican American Cultural Center, along with other improvements to libraries and museums. Of that funding, the arena received $180 million, the children’s museum $19 million, and the Mexican American Cultural Center $5.75 million.

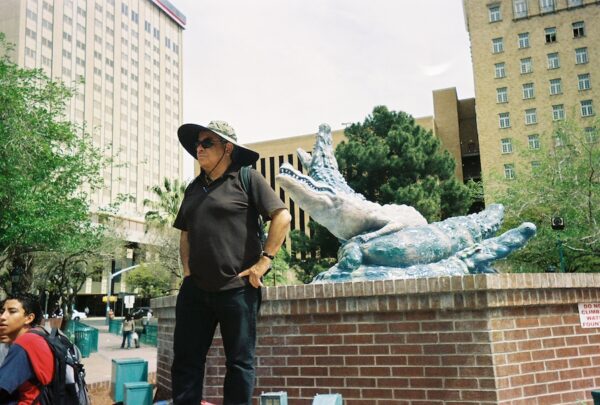

Sandoval protecting Luis Jiménez’s Los Lagartos sculpture from fellow protestors at a Cesar Chavez Day demonstration in downtown El Paso. Photo by Claudia Rivers.

The “multipurpose arena,” which is part sports arena, part performing arts venue, has been a topic of community ire. It is proposed to be built in one of El Paso’s oldest neighborhoods, and is thought by some locals to be a project that favors wealthy El Pasoans over the rest of the community. In 2018, El Paso City Council approved a vote to combine the Mexican American Cultural Center (MACC) with the library downtown, sparking outrage from the community who advocated for two separate spaces. The proposal would take 40,000 square feet from the 100,000 square-foot main library, which had recently been expanded as a result of a bond passed in 2000.

Sandoval was intent on his collection going to the forthcoming Mexican American Cultural Center, says Ben Fyffe, Director of Cultural Affairs and Recreation for The City of El Paso, via email. Fyffe confirmed there had been numerous discussions with Sandoval over the years about placing his art collection within a City of El Paso cultural facility.

“In 2015, when planning began on a bond-funded municipal Mexican American Cultural Center (a block away from EPMA), Juan was very intent on his collection going there. However, from [the] earliest planning stages, that facility (like most cultural centers) was not envisioned as a collecting institution but rather a space that would host rotating exhibitions, artist residencies, theatre and dance productions and culinary programs,” says Fyffe. “The plan for the MACC remains to utilize the collections of its fellow municipal museums like EPMA as well as book traveling exhibitions. Juan ultimately was not happy and despite efforts to show that EPMA was better equipped to care for and interpret the collection, discussions stopped.”

Sandoval served on the acquisition committee at EPMA for a few years and was familiar with the museum’s acquisitions procedures. He knew it was unlikely his collection would be accepted into the museum’s permanent collection in its entirety, says Rivers. As one of Sandoval’s closest friends, Rivers speculated that Sandoval, a longtime librarian, may not have approved of the library losing half of its space for a cultural center that was conceived as a stand-alone facility.

“I think he knew that he did not have a lot of time left, and the fate of the Mexican American Cultural Center in El Paso was not at all settled,” says Rivers.

Fyffe’s sentiments reflected those of many El Paso residents: that the move of Sandoval’s historic collection from the community which he nurtured (and nurtured him) to Austin was a missed opportunity for the city.

“Juan Sandoval was always a bright spot in the local arts community, with a powerful presence and incredible commitment to supporting emerging artists. Although we ultimately respect Juan’s decision to deed his collection as he wished, it was a loss for El Paso,” says Fyffe.

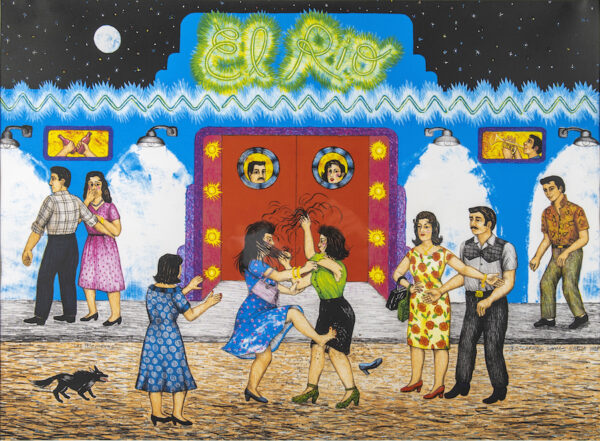

Carmen Lomas Garza “The Fighters, Las Peleoneras” 1988, color lithograph on paper 321/2” x 391/2” Courtesy the Mexic-Arte Museum

The Sandoval collection comes to the Mexic-Arte Museum during a time of big change, by way of a $20 million dollar bond-funded renovation project. With its renovation, Mexic-Arte plans to have a public library space and a permanent exhibit of rotating selections from Sandoval’s art collection. The renovation plans have yet to be finalized, but Orozco says they will maintain the facade of the building (which can be traced back to The Directory of Austin for years 1885-86).

Orozco says at Mexic-Arte, Sandoval’s collection will be housed in a dignified building in the capital city. Mexic-Arte, as one of the only Mexican/Mexican American museums in the country, has shown the work of many El Paso-based artists, and behaves like a regional museum that represents the whole of Texas, and takes exhibitions to other parts of the state whenever possible.

“I think that Juan knew donating his art and books, because he knew Mexic-Arte was a book collector in addition to being an art collector, it would make an impact; it would create a foundation, strengthen the Mexic-Arte museum, and his collection would be a cornerstone or an anchor to our museum,” says Orozco. “He knew together we would be stronger.”

Those who knew Sandoval personally said he was intent on keeping his collection intact, and Mexic-Arte’s collections policy aligned well with that vision.

Says Ray Griggs, Sandoval’s nephew, who helped manage his estate after his passing: “In private moments with him towards the end, he shared with me how grateful he was to Mexic-Arte for the legacy which he is leaving, that they are taking care of, and that his work, his art collection, his passion, will continue to be shared for generations.”

Griggs says his uncle helped him live a well-balanced life, offering a liberal perspective which contrasted with his conservative military surroundings. Griggs recalls a time when he entered the U.S. Naval Academy as a young man and his Uncle Juan gifted him two impactful novels, The Psychology of Military Incompetence, and The Good Soldier Švejk, a Czech anti-war novel.

“I think that’s what he did for hundreds if not thousands of young men and women, and his friends also. He really enjoyed opening up the minds and the hearts of people to what was possible,” says Griggs.

Sandoval’s door was always open to visitors, says Griggs. In his role as a librarian at UTEP, from 1981 to 2019, he influenced generations of students. Sandoval was also a point person for Chicanx studies, interdisciplinary studies, and was the bibliographer for languages and linguistics. “He got to know people because he would go out and walk around and show people around the library rather than just sitting behind the reference desk,” says Rivers.

In addition to his scholastic role, Sandoval kept in touch with many El Pasoans by attending art openings and sitting outside on his porch drinking tea in the morning, chatting with passersby. Griggs says Sandoval was always looking for quality in people, and in things. Sandoval would frequently summer in Oaxaca, Mexico, and took great care in surrounding himself with meaningful, personalized items even on vacation.

“He would travel with seven suitcases. He would take his own sheets, pillows, tablecloths, the cutlery, french press,” says Griggs. “When he showed up somewhere, even if it was just a hotel room, [or] a home he rented for the summer, he would set it up the way he wanted.”

Rivers says her and Sandoval became known for attending to art openings together. He introduced her to many locals and artists when she first arrived at UTEP. “My husband doesn’t particularly like to go to art openings. And so when I’d say, ‘You want to go to an art opening?’ he would say, ‘No, why don’t you take your other man?’ It was just one of those things,” Rivers laughs.

Rivers and her husband drove down to Oaxaca one summer to stay with Sandoval, and when they arrived he was on his way to an opening at the textile museum. He brought them along immediately without giving them a chance to unpack.

Rivers and Sandoval also made regular trips to the book fair in Guadalajara and at The Museum of Juárez to select works for the UTEP library. On one trip, Sandoval collected an antique book in Juárez called Marcas De Fuego, which can help identify book brands and watermarks from libraries in Mexico. Rivers says she was glad to see that particular book go to the library’s collection. Because many libraries rely heavily on electronic resources, one of the few areas in which libraries differ is in their regional collections, says Rivers.

“In our special collections department we try to collect on the border region, our part of Far West Texas, and Southern New Mexico and Northern Mexico. Juan was very helpful in building that collection, as well as the Chicano literature and the Chicano Studies collection.”

Thanks to Sandoval’s curious nature, careful curation and impeccable taste in people and things, Texas gained a world-class Mexican and Latinx art collection with the power to endure. Orozco, who found a kindred spirit in Sandoval, says his mission to collect and support border region artists has strengthened her resolve to see the Mexic-Arte Museum into its next phase as a cultural institution.

“I feel even a greater purpose to complete the mission of bringing this museum to total fruition, in the museum building, with the beautiful Juan Sandoval collection, paintings exhibited and the library all catalogued and organized,” says Orozco. “I feel even more obligated. I now have his mission, too. I’m honored to carry on his work and help carry on his legacy.”

Note: This is Part 1 in a two-part series. For part 2, please go here.

5 comments

Fantastic article on a very important life.

Being from El Paso and having tried to publicly drive home the point that Juan’s unparalleled Latino(a)/Mexican art collection and related books would have been the key to establishing El Paso as THE LATINO CULTURAL CAPITAL of America, it was sad but completely expected that it would end up in a city like Austin that respects and appreciates important and influential people like Juan Sandoval.

Ben Fyffe (mentioned in the article) and other people in the Museum and Cultural Affairs dept. along with elected officials and public servants are absolutely responsible for this embarrassing and abject failure to appreciate and do whatever it took to make Sandoval’s art and book collection part of his legacy to El Paso and the 83% Latino community living here.

When you are a city that is 83% Latino, is uniquely positioned on the border and is saturated with the culture and heritage of Latino pride, you do what is necessary to secure it.

Instead, we have a culturally tonedeaf “leadership” that insults Latinos by only allotting $5 million to a Mexican American Cultural Center to represent our unique place in America (and morphing in into the Main Library), while the Children’s Museum budget has grown to $75 million and the fiscally stupid sports arena fustercluck will cost taxpayers easily over $400 million if it ever survives litigation.

My congratulations to the Mexic-Arte Museum of Austin for having the foresight and appreciation that we couldn’t seem to muster up when it mattered. And my thanks to the late Juan Sandoval for leaving behind a legacy that will inspire millions over the years.

Thanks to writer Mary Cantrell for the enlightening story.

Juan Sandoval-What a wonderful person he was. Great collector and friend. Glad his art collection is in good hands.

What a wonderful story! And what a treasure Juan Sandoval left Texans and Mexican Americans from sea to shining sea. He was wise to leave his collection to MexicArte Museum in Austin, a progressive and artsy, diverse town that will embrace his collection.

Thank you, Glasstire, for a well written and well researched article. Mexic-Arte Museum and founding director Sylvia Orozco are worthy of the gift and will remain good stewards of the collection. Master collector Sandoval also continued with this gift his devotion to supporting the careers of contemporary artists; Sylvia Orozco is a talented, academically trained visual artist herself.