David Politzer is the Director of the School of Art at the University of Houston.

Given all that happened in the past year, it’s a miracle to see the Class of 2021’s work so elegantly exhibited in the Blaffer Museum at the University of Houston. Neither the pandemic nor the other rattling events of 2020-21 slowed these students down or compromised the rigor of their work. It may be just the opposite, actually.

When we pivoted to learning online, it wasn’t long before we felt the loss of intimacy. Looking at art without being able to greet each other’s work in the flesh was a huge blow. Even “two-dimensional” art has dimension, which is very difficult to translate over a video call. Being in one another’s studios allows us to be vulnerable; it’s a letting-in to a creative production space, where we can observe the discarded false starts in the corner, the frivolous doodles at the edge of the desk and the exciting first scratches of a new idea.

On screen, we’re relegated to the defined space behind the person, which is too often a carefully curated bookcase, an innocuous blank wall or a canned digital background like the screensavers and wallpapers popular 30 years ago. Although it goes against so-called best practices, I would appreciate seeing a good mess, a visit from a pet or child, or a coffee mug that reads, “This Ain’t Coffee!” Like the frivolous doodle, these visual distractions give us insight into the creator of the creative works.

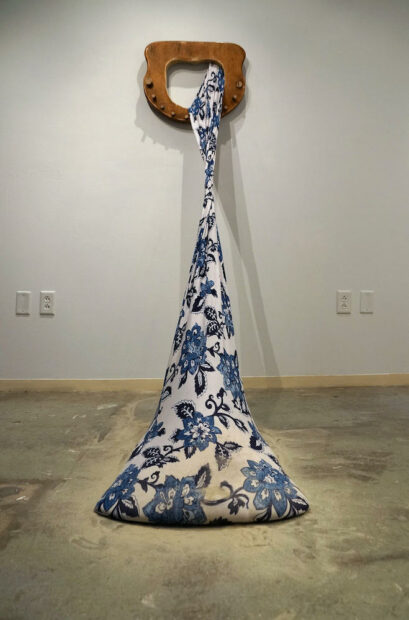

Stevie Spurgin, Self Portrait, 2020. Image on fabric, stuffed, sewed & used makeup wipes, 35 in x 24 in. All images courtesy of the artists, and David Politzer.

Even as this cohort of students adjusted to new ways of learning and making, their predecessors, the Class of 2020, grappled with loss as Covid forced the postponement of last year’s Blaffer exhibition indefinitely. 2021 sculpture MFA Stevie Spurgin was devastated, “It broke my heart. Then it was like, ‘Oh my gosh, what if we don’t have a show either?’” Without the typical in-person culminating events and group celebrations, students are left without closure.

Robert Legans-Johnson, identity failure, 2020.

Instagram face filter, luster inkjet print, variable, 12 1/2 in x 25 1/3 in.

IPEF student Robert Legans-Johnson described how Covid disrupted his ability to connect socially. “I love technology but social media is not enough. It takes me a while to get adjusted. As an undergrad I spent three years of building up confidence so I could socialize comfortably during my fourth year.” He hoped to follow a similar trajectory as a graduate student, blossoming socially in his third year. The isolation wrought by the pandemic has interrupted the final steps of solidifying a tight community.

The disruptions to our everyday routine have been too numerous to count. While most of the buildings on campus were either closed or open at a very limited capacity, the studios in the School of Art were designated essential research labs and remained available for student use. Many students chose not to come to their studios on campus, a particularly difficult personal decision. For some, the only safe choice was to move into a home studio, or a virtual studio, which meant drastic shifts in scale, materials and privacy. Through clenched teeth, some students mentioned their family members as not always sympathetic witnesses to home studio practice, who weren’t thrilled about new messes, or could not understand why Dad was doing arts and crafts but couldn’t play right now.

Our graduate students have the option to teach in their second and third years, and many of them still did. They are a vital part of our expanding faculty community and as such they also invest emotionally in our undergraduate students. Many members of the class of 2021 were in their first years of teaching when the pandemic hit and were at the forefront of our shift to remote teaching. They saw their own feelings of fear, isolation and confusion mirrored in their students and were forced to play many roles: teacher, student, mentor, counselor, motivator, confidante and friend. Even the most committed teachers lost touch with their students, some of whom completely disappeared after the move online. Sculpture MFA Marie Williams said that during video calls we’re “staring straight into each other’s faces and that gets exhausting and draining to make constant eye contact.” Graphic Design MFA Samiria Percival observed of her students, “This age group is incredibly hip to the digital environment. Many are suffering from depression and anxiety and I think that digital connections are helping. Many students like to have their cameras on but also like the control of turning them off.”

Most of what I’ve written thus far will sound familiar — the anxieties and discomforts of the pandemic have touched us all. I recount them here to put this show in perspective and describe a relentlessly grim backdrop behind a remarkably resilient group of individuals. How did they find the motivation to continue their creative practice through this turbulence?

First, let’s consider the technology: while video calls are exhausting, lack warmth, and are subject to technical snafus, they are an incredibly useful and versatile tool. (Can you imagine how far behind we would be if we didn’t have Zoom and the Internet?) Many teachers and students have said they truly enjoy online learning. Beyond the flexibility to learn in your pajamas with your cat in your lap, or on your own time, students found a lot to like in the online format. Painting MFA Wanda Harding said that with the separation the screen provides, she was able to untangle the personal from the professional with ease during a video call, protecting her feelings from the sharper comments during critiques. Stevie Spurgin said that teaching online forced her to think about sculpture in an entirely new way, as if reinventing the medium. She stated confidently, “My job is to teach students what sculpture can be.”

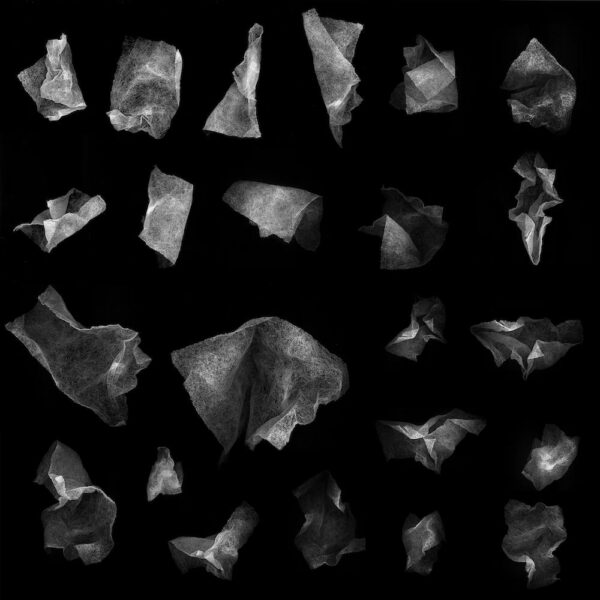

Marley Foster, An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, 2019. Sand, stretch cotton casing, seat of a kitchen chair, 2 ft. 6 in. x 5 ft. (approx.)

Sculpture MFA Marley Foster knew at the outset that sharing her work via a video call was going to be challenging. She was concerned about the translation of the objects into photographs. Gradually she started thinking of photography as more than just a means of documentation, and she began taking self-portraits while interacting with her sculptures. A hybrid practice of photography, performance and sculpture emerged from what she first saw as a problem. “This wouldn’t have happened if not for the shift to online,” she said.

While there are far fewer stop-and-chat opportunities given our social isolation, students reported that scheduled critique meetings required more preparation and were therefore more efficient. With the use of online calendars, assistive scheduling websites and a ticking clock in the corner of the screen, students felt that the digital environment kept them on track, and they were able to accomplish more.

Teaching was another way students grounded themselves during this difficult time. Graphic Design MFA Virginia Patterson said that “It was comforting to know the expectations of teaching. And seeing my students succeed felt very satisfying. Their commitment and resilience inspired me.” Photography and Digital Media MFA, Katie Lanier, said, “Teaching has been my solace during the pandemic. I have to show up for my students and that has been vital to my mental health through all of this. We hold each other accountable.”

One painting MFA was motivated to develop and teach their own independent, online course over the summer. They crowd-sourced students using social media, assembling a community of folks who were passionate about color theory. The student said, “The virus is invisible but color is everywhere, you can’t help seeing color. It’s like breathing.” This new community found it comforting to engage about something visible and tangible.

When I asked Samiria Percival about her next steps, she laughed, said that that was my scariest question, and held up a pair of scissors and a colorful inkjet print, adding: “I’m just trying to get this stuff up at the Blaffer.” But then she went on to describe her efforts to offer graphic design workshops online and printable PDFs, making advanced learning tools available to communities who don’t typically have access to college-level curricula.

A few students voiced gratitude for not having been severely affected by the pandemic and took some solace in the alone time. Painting MFA Marky Dewhirst suggested that because art-making is such a solitary activity, the pronounced isolation “launched me into thinking more deeply about what I’m doing. It has allowed more time to think and read.” She acknowledged that this was a privilege and that being able to attend a graduate program on scholarship created a unique opportunity to concentrate on her thesis work, free from a number of responsibilities. Marie Williams said she appreciated the time “to reflect inwardly. I spent a lot of time in my garden because I needed to be around things that were growing.”

Veronica Gaona, an MFA student in the Photography and Digital Media program, was grateful for how the pandemic forced her to slow down. She said, “I had to stand still and really reflect on my relationships. Having to adjust was difficult but it brought me some peace when I looked at my friends and family members and take stock of what’s important.”

Samiria Percival was one of many students who weighed tough Covid-related financial and personal factors, and ultimately decided to move away from Houston. In a truly serendipitous coincidence, she wound up relocating down the street from one of her favorite professors, who also calls Baton Rouge home. Samiria described the bond they formed: “…it feels good to have that connection. Dr. Plummer has already introduced me to the art world out here.”

With the advantage of some hindsight, Wanda Harding shared that she experienced an overwhelming creative block during the past year. Covid and the stress of the political environment, compounded with the frustration of feeling blocked, created a cycle of paralysis. Professor Raphael Rubinstein told her, “You can’t make yourself make more work.” She eventually came to accept the block, which ultimately set the stage to ease out of it.

Jamey Hart, Thinking With Concepts, 2020. Wood, metal from museum frames, nails, twelve equivalent objects, hooks, glue, other things, 15 x 17 x 3 in. (approx.)

During Summer 2020, we moved our entire MFA studio operation to a new building, Elgin Street Studios. With gorgeous natural light, high ceilings and two elegant exhibition spaces, the new building marks an exciting new chapter for the school as, for the first time, all of our MFA students are under one roof. Katie Lanier said, “The new studios have brought new ideas to my practice, I truly don’t think that I would be making the work I am currently making if I was still in the old studios. Environment is vital to an artist’s productivity.” During the early days of the pandemic, before the studios even had tables or chairs, I was delighted to see students in Elgin Street masked and huddled in their studios, sitting on the floor, eager to get to work.

Many students said that the opportunity to mount solo exhibitions in the Elgin Street Galleries was surprisingly motivating. The thesis exhibition, as in past years, is a large group show that students have been working toward in a sustained way for at least two years. The Elgin Galleries offer a new, alternative space to experiment and take risks in a professional gallery setting, without the high-stakes expectations of the thesis exhibition in the Blaffer. “I want to fill that up!” was Wanda Harding’s reaction, remarking how it would be an opportunity to show sketches, some “B-Side” type work, motivating her to think differently. And Marky Dewhirst excitedly described her upcoming show, “It could be a bomb!” Yes! Explosive and unexpected.

When Veronica Gaona deinstalled her solo show at Elgin Street, she reflected on the experience, “I can see this work out in the world. The show made me feel like I can expand my ideas, I can make these bigger and propose the body of work in another space.”

These students are all exceptionally driven and are not likely to let anything stand in the way of making work or finding success through that work. This exhibition in the Blaffer Art Museum is proof of the resilience, grit, patience and progress they displayed over the past three years. When asked to reflect on their time in the School of Art, and identify areas of personal growth, the responses were quite encouraging. Robert Legans-Johnson said that before coming to the School of Art, he knew he was a creative person, but wasn’t sure where he fit in. Now he confidently identifies as an artist, and says that while “that is a bit scary, I’ve amassed the qualities and indicators of being an artist.” Or perhaps, he released them from within and now feels comfortable identifying as an artist.

For Virginia Patterson, who spent nearly a decade doing client-based work before she came to the SoA, the initial steps toward honoring herself as her most important client came when she was a first-year student. Comparing the work she made her first year to her thesis work, she noted that, through trial and error and some tough love dispensed by SoA faculty, she learned to trust her instinctual imaginings and expand her notions of successful design.

Marky Dewhirst said somewhat sarcastically that she arrived “…making perfectly adequate paintings. But there was a huge shift. Now my eyes are completely opened and I think more deeply about what I’m doing.”

Marley Foster said, “I found a lot more support here that I didn’t know I needed. I was offered more help than ever in my life.”

The sphere of influence of the pandemic is enormous and exhausting. It forces us to be hyper-conscious of everything we do outside our homes. For the most part, slowly, we have adapted and accepted the necessary changes to slow the spread of Covid. This is in part due to the hope that some sort of relief or shift back to the way things were in January 2020 is coming. But none of these promises — of a vaccine, of herd immunity, or more accurate testing — will be like rebooting the computer after it freezes. The side effects of the pandemic will be with us, long after any of these promises come to pass.

This brings to mind the Stockdale Paradox, made famous by Jim Collins in his book on leadership, From Good to Great. Collins uses the experiences of Admiral James Stockdale, a pilot and POW during the Vietnam War, to highlight the difference between hopeful optimism and faith that’s rooted in an honest assessment of your situation, no matter how dire. Or as Mel Brooks said so succinctly: “Hope for the best, expect the worst.” The Class of 2021, despite all that was thrown at them, managed to persevere, confronting the brutal facts of a pandemic while maintaining faith every day that their creative works were important. As Stevie Spurgin put it, “I had to convince myself that this was my new life. I can ride it out until it gets back to normal. If there is a such thing as normal anymore.”

UH School of Art 43rd Annual MFA Thesis is on view through April 11 at the Blaffer Art Museum, University of Houston. Note: This essay appears in a slightly different form in the exhibition’s accompanying catalogue.