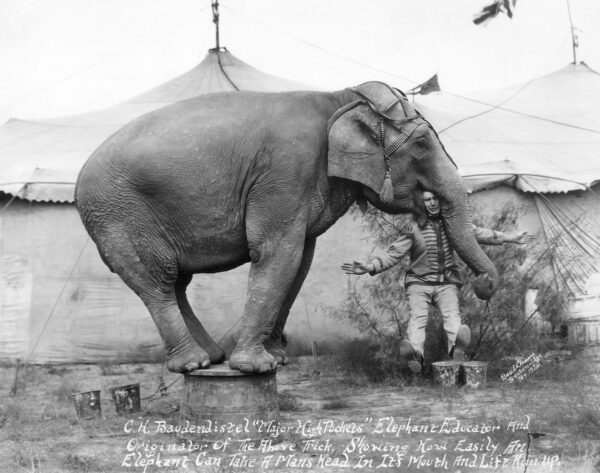

Basil Clemons, Circus in Breckenridge, Texas, 1926, Elephant holding C.H. Baudendistel. “Major High Pockets”, elephant educator and originator of the above trick, showing how easily an elephant can take a man’s head in its mouth and lift him up. Photos: Courtesy of the Basil Clemons Photographic Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.

Madam Rainey’s Jazz Hounds and Broadway Strutters rolled into Breckenridge, a roaring Texas oil-boom town, in 1922. Just a few years earlier, the county seat of 1,500 souls had not been populous enough to draw touring performers. But after 1920, when black gold burst from the earth and the population shot to 30,000 people, circuses, Wild West shows, and dance and drama troupes came in droves to entertain the roughnecks and wildcatters, the honky-tonk queens and gamblers, and the hard-working business folks who catered to the boomers.

Basil Clemons, Madam Rainey’s Jazz Hounds, African American musicians, Breckenridge, Texas, 1922

Gertrude Rainey adopted the professional name Madam or Ma Rainey after marrying William “Pa” Rainey in 1904. Accompanied by the Jazz Hounds on drums, violin, bass, and trumpet, they performed a comedy-and-dance routine throughout the rural South well into the 1920s. Madam Rainey signed a recording contract in 1923, releasing over 90 blues numbers over the next five years and greatly influencing blues singers who would become better known than herself.

Among those who found their way to Breckenridge, the eccentric photographer Basil Clemons documented the oil fields and the traveling shows, as well as local traditions, scenes and lifeways, for three decades. Seventy-three of his images are on view in Basil Clemons: Witness to a West Texas Boomtown at The Old Jail Art Center in Albany through January 30. Clemons’ photographs have a hardscrabble grace about them, with a rawboned edge that is sweetened with Main Street exoticism. Breckenridge’s social gatherings, shop windows, and bustling, derrick-strewn townscape often appear just as strange, in an oddly comforting and familiar manner, as the traveling shows that blew into town, worked their magic and mojo, and then vanished down the rails and roads.

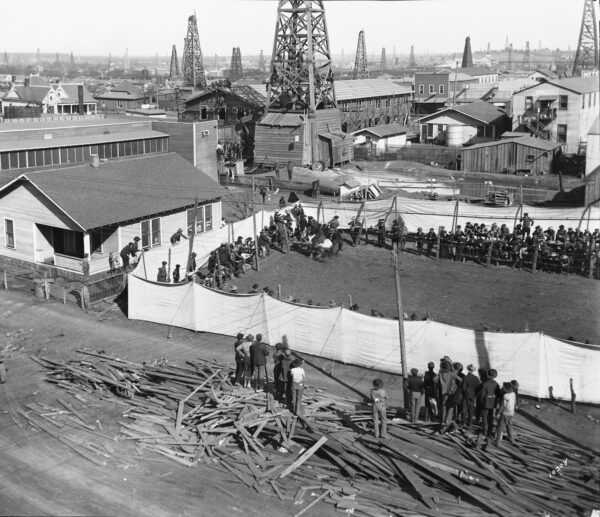

The exhibition’s keynote image, Breckenridge, Texas – The Great Oil City, offers an uncanny view of the boomscape, with a forest of wooden derricks sprouting amongst the houses and commercial structures. Fossil-fuel towers even flank the county courthouse. Tents pitched in yards and alleys housed boomers who couldn’t squeeze into hotels or rooms for rent. Another image in the exhibition, identified as People watching a rodeo show, provides a closer, bird’s-eye view of derricks in a neighborhood. A budget rodeo is in progress, its patrons standing between canvas outer walls and a hastily-constructed rodeo fence, within which beleagured cowboys attempt to lasso spirited mavericks.

In their 1997 book about Clemons’ images, Jazz-Age Boomtown, Jerry L. Rodnitzky and Shirley R. Rodnitzky theorize that Clemons, a commercial photographer who provided any photograph service requested, likely seemed especially drawn to circuses and Wild West shows because of his own background. Born in 1887 as the oldest of seventeen children, he left the family’s East Texas home at age sixteen, headed for California. He somehow found work as a pioneer cinematographer in Hollywood’s infancy, then went on the road with the Tom Mix Wild West Show. He photographed the Alaska gold rush and opened a photography studio in Seattle before hitting the road again with a circus. Touring Texas with the troupe, he learned that his Seattle studio had burned and wound up in Breckenridge, where he lived in a former ranch chuckwagon on a vacant lot and motored around in a stripped-down Model T. The Rodnitzkys describe him as “a Texas-style Thoreau” and a “boomtown bohemian.” Rather than measuring the amounts of chemicals that went into his darkroom fluids, he tasted the mix of substances to arrive at the proper formula.

Basil Clemons, Circus; Bluey Bluey, Mighty Smithy, and Madam Mimir, three acts with the Alamo Exposition Shows, under the auspices of the American Legion, Breckenridge, Texas

The touring performers Clemons photographed often exhibit a gypsy vibe. An undated image entitled “A large group of costumed actors pose for an outdoor photograph” encompasses clowns, cowboys, magicians, jesters, and players festooned as all manner of romantic and unusual characters. A circus image titled Some Gentry Bros. Clowns captures figures that seem to have been caught adrift in some liminal dimension, the interior of the circus tent offering a portal. A 1926 image, Circus; Bluey Bluey, Mighty Smithy, and Madam Mimir, three acts with the Alamo Exposition Shows, under the auspices of the American Legion, Breckenridge, Texas, bears a shortened title on the original print, in Clemons’ characteristic flowing white ink. An amazing array of local folks are gathered around a sideshow pitchman as he touts the mysteries of “Bluey Bluey from the Land of Lilliput” and “Madam Mimir” and her “Psychic Marvel Revelations.”

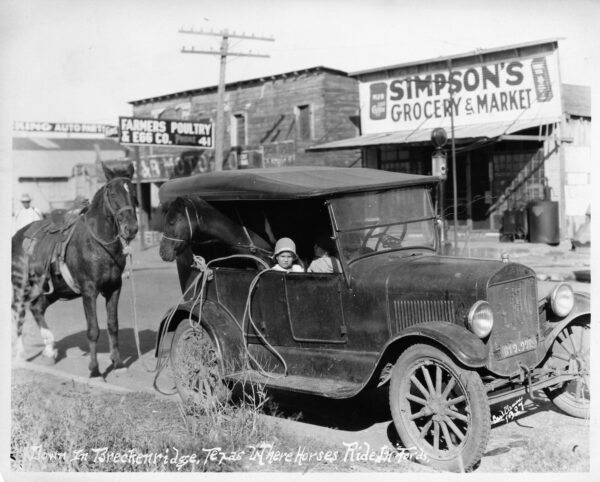

Basil Clemons, Down in Breckenridge, Texas where horses ride in Fords. Horse in backseat of Ford motor car outside Simpson’s Grocery, Breckenridge, 1927

Down in Breckenridge, Texas Where Horses Ride In Fords, reads Clemons’ handwritten title on a photograph of a horse sticking its head out the back side window, two young children sitting in the front. Other activities depicted include baby contests, rattlesnake hunts, parades, contests to win a prize turkey, a pecan display at the Oil Belt Fair, high school football games, child boxing matches, and other pastimes of the American grain. A pair of gleaming silver storage tanks adds a sci-fi touch circa 1937.

Old Jail Art Center Executive Director and Curator of Exhibitions Patrick Kelly selected the show’s images from nearly 5,000 Clemons photographs that have been digitized by their permanent archive, the University of Texas at Arlington Special Collections. The library’s Basil Clemons holdings consist of 12,000 silver gelatin prints and roughly 5,900 nitrate, safety, and paper negatives. Every image in Witness to a West Texas Boomtown is archived on UTA Special Collections’ web pages, and I’ve indulged my desire to see some of the show’s images enlarged, relishing the enhanced detail. The complete 4,919 digitized images also beguile as a time-warp rabbit hole. Some favorites I’ve plumbed or stumbled upon that aren’t in the OJAC exhibition include Clemons’ image of this group of Native Americans at the 1925 West Texas Chamber of Commerce convention in Mineral Wells, and this undated, atmospheric view of downtown Breckenridge during the boom.

My trek to Albany was my first Art Road Trip since the pandemic hit. It felt sooo good to roll through rural and small-town Texas, let the mind wander and the big sky country unkink the cloistered perspective of quarantine. A pilgrimage to Albany is among the safest outings, pandemic-wise, one may currently make. Moreover, The Old Jail Art Center — with its stellar collection of European, Asian, American, and Mesoamerican art and its commitment to cutting-edge contemporary work — is among the most unique institutions in the state whenever one visits. Other highlights of my recent trip include Deborah Butterfield’s Three Sorrows and Paul Klee’s 1934 Oil and encaustic on plywood, Der Weg ins Blaue (Path into Blue). And perhaps most unusual for a fine art museum, one small gallery in the Center features changing exhibits on the region’s fascinating frontier history. And I never tire, when headed for Albany, of rolling through such area outposts as Cisco and Rising Star.

‘Basil Clemons: Witness to a West Texas Boomtown’ through Jan. 30 at the Old Jail Art Center, Albany, TX