I am going to attempt, by writing this, to evoke the spirit of the Snowman Burl Ives — the benevolent banjo-playing Christmas demon who narrated the 1964 stop-motion version of Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer — come to tell a winter story to a squirrel. That snowman’s name was Sam, and he showed up each December of my early childhood to help fortify my secular fairytale idea of Christmas. In 1990, when I was three, I considered Sam a personal hero. I might still. He is soft-spoken, jolly, and, like most talking snowmen, deeply weird when one stops to think about it. If I remember correctly he provides exposition from a snowy, tree-dotted expanse that sits at a slight remove from the story’s main action. At one point he sings a song about ornaments.

One warm evening this past December, I encountered a big plywood Sam in some neighbor’s front yard. Neighborhood walks were the prime activity of 2020, and they often shook loose some weird ideas. The sight of my childhood snow-Idol, propped up and spotlit at the base of a tall magnolia tree, brought forth some of the strangest of these thoughts. I found myself looking back over my life thus far, while simultaneously scheming futures that might please the toddler version of me. The next morning, taking all the wrong cues from that moment, I opened a new online stockbroker account and bought shares of Snowflake Inc. (New York Stock Exchange ticker symbol: SNOW), ManpowerGroup Inc. (MAN), Burlington Coat Factory (BURL), and Wedbush ETFMG Global Cloud Technology (IVES). It soon occurred to me that this was likely a terrible idea, since I had only heard of one of those companies and was profoundly underemployed. So I retreated and withdrew my money after losing seven cents. I fear the stock market. Plus, I already have this territory covered in another class of assets: I collect snowman art.

The collection is small — four objects and a screenshot — and I want it to stay modest. I already feel dirty for calling my snowmen “assets.” The works are by no means intended as investments, at least not in the financial sense. They are more like little white cairns that guide me toward acceptance of one specific failure as a photographer. There are snowman photographs that I have wanted to make for years, but I have a problem; I have lived in Arizona and Texas the whole time. The snowmen I’ve known have mostly been plastic, worn cowboy hats and carried stick horses. Each and every one of these has charmed me, yet they are all so permanent and cartoonish that while they resemble snowmen, they do not really seem to mean snowman. They are decorations, and they only connote Christmas.

Actual snowmen, the ones made of snow, are less specific and more complicated. They contain a lovely sort of chaos within their cold bodies. They are often shabby, always ephemeral reminders of fresh-snow exuberance. Their makers are people who likely thought, simply and intuitively, “I want to make a snowman.” Most good art comes from a similar impulse.

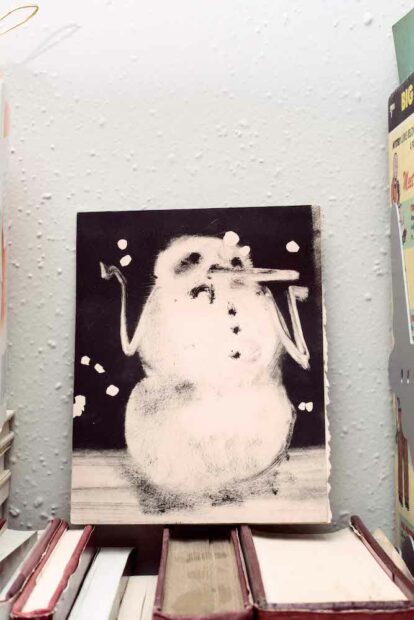

The artworks in my snowman collection channel the real things in ways that Christmas decorations cannot. Look at this print by Bea Parsons. This is a snowman in motion. It seems to have pulled a Frosty and come to life, yet it celebrates this miracle with a shrug. This is arguably a very human response to such a phenomenon. The picture is a sketchy and muted monochrome, and the shading around the — is it a butt? — may indicate dirty snow. Real snow. This snowman’s world is closer to our reality than it is to any Christmas-land. Most surprising is the degree to which a new type of fantasy is discovered within the drab space. This snowman is an indifferent winter spirit for our world.

Bill Davenport’s Stupid Snowman, meanwhile, retains a lot of real-snowman messiness while distilling itself down to the most essential parts: lumpy white spheres and sticks. A scale shift transforms “stick” from a spindly arm into a wobbly armature that rests against the body like a discarded broom. The snowman seems unsure what to do with the stick, with itself. It has an almost soggy weight. It is a stupid snowman. It is a smart sculpture. It is, I think, a comedian.

Uline Snowman, by Glasstire’s own Brandon Zech, also brings humor to basic snowman architecture. This small collage is made out of pictures of toilet paper that were cut from a Uline catalog. Bits of product copy on the reverse page are visible through the paper. The snowman smiles, carrot-nosed and marshmallow-like, from a plain white backdrop that makes a fine stand-in for snow. This man seems not to know that it is actually a toiletpaperman — a vaguely relatable misunderstanding. Maybe all snowmen are stupid in their own ways. The real ones just stand there and melt in the sun.

Then there is this piece that my mom made out of a sock. It was a Christmas gift; I forget when exactly. My primary attachment to it is obviously sentimental, but it holds equal weight in the collection. This snowman appears deeply innocent and quite fragile, with little twig arms and pin-eyes that need regular readjustment. I love this sculpture made of various sewing scraps. It exemplifies the art-impulse of every snowman maker. Sometimes snowmen must be brought into the world, even if there is no snow. This is a joy that makes art exciting, and one that can help shorten all sorts of distances.

Family is too big of a story. In Phoenix, in the house where I grew up, I believe there is a water-damaged drugstore print in a disproportionate frame. It may be the only photograph that depicts me with both of my parents. In it my mother wears a black and white striped shirt, my father has gray hair and a mustache, and I am approximately three years old. All of us are smiling. On the ground in front of us, rising not even to the height of my small knees, is a little lump of a snowman. It snowed in Arizona, in the desert! Just a dusting, but still significant — I recall no other instances in my life there. According to the picture we capitalized on this rare event as a family. A miracle, quick to melt away. Thankfully someone else was there at the time with a camera.

Thinking of this, I want badly to get out and photograph some snowmen. Failing that, I want to see them photographed. For this reason, the final item in the snowman collection is a screenshot from Amazon of David Lynch’s photobook Snowmen. The actual book, published by Steidl Verlag, is out of print and expensive. My screenshot shows the series of deadpan black-and-white photographs of snowmen in winter lawns. In one picture a three-segment snowman with flailing stick-arms smiles at something out of frame to the left. Another picture shows something similar, but the snowman is looking at David Lynch. I wonder if anyone other than a famous director could have these simple — though admittedly well-crafted and weirdly haunting — pictures published by a company with the reputation of Steidl. Then I remember how such concerns are unimportant, and my envy turns away from questions of status and back toward some familiar fussing over geography. I fantasize about living someday in a place that is not a desert or a swamp. Until that day comes, I have my collection.

1 comment

You should check out my friend Bob Eckstein’s book, The History of the Snowman.

https://allthatsinteresting.com/history-of-snowmen