Installation view: Flores Mexicanas: Women in Modern Mexican Art. Feb 16, 2020–Jan 10, 2021. Dallas Museum of Art

Frida Kahlo is a household name. If you ask anyone to name a female Mexican artist, they’ll probably say Frida. And thanks to the endless Kahlo-inspired books, movies, and merch that have mushroomed in recent years, they’ll probably also tell you what she looked like — the colorful dresses, the braided hair, the famous eyebrows — before they name any of her artworks. The average American “knows” Kahlo. But what about the other female Mexican artists working at the time? What else could a modern Mexican woman be?

Flores Mexicanas: Women in Modern Mexican Art at the Dallas Museum of Art surveys the ways that Mexican artists depicted women during the tumultuous first decades of the 20th century. The Mexican Revolution brought seismic shifts that were both reflected in and shaped by the country’s artists. “This is a moment where people are wanting to completely change the social, artistic, and cultural order, but then they realize that it’s changing in ways that were not what they intended,” exhibition curator Mark A. Castro told me in a recent Zoom call. Before the war, images of Mexican women focused on urban, European-descended, femmy aristocrats. After the war, the country’s daring female artists forged a new picture modeled after themselves and who they wanted to be. Here are some of their stories.

Olga Costa, Self-Portrait, 1947, Colección Andrés Blaisten, México. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York SOMAAP, Mexico City

Olga Costa was born Olga Kostakowsky Fabricant in Leipzig, Germany in 1913. Her family immigrated to Mexico City when Costa was 12, after her father — a Ukranian violinist, orchestra director, and composer — was freed from jail following a political sentence for his Socialist activism. Although she originally trained as a musician, Costa switched gears after seeing one of Diego Rivera’s murals at an amphitheater. She enrolled in the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas in 1933. There, Costa studied with the painter Carlos Mérida, who later called her “the white angel of Mexican painting,” and met her husband, the artist José Chávez Morado, in a lithography course. However, Costa’s studies were brief. Financial troubles forced her to leave the school after only three months, so she was essentially self-taught.

According to the art historian Raquel Tibol, Costa “detested any rule or theory that tried to distinguish trends or values in art.” While Costa didn’t adhere to a specific art style or group, her pictures of people are consistently piercing. In her 1947 self portrait, the artist shows herself turning around to confront the viewer, her eyes meeting ours as she grips a paintbrush in her left hand. “The male artists [of this period] are still pigeonholing women into certain tropes that you’re either a victim, a passive participant, a happy craftsperson, or a mother,” Castro says. In contrast, with this picture Costa situates herself as an active creator and contributor to Mexican cultural life.

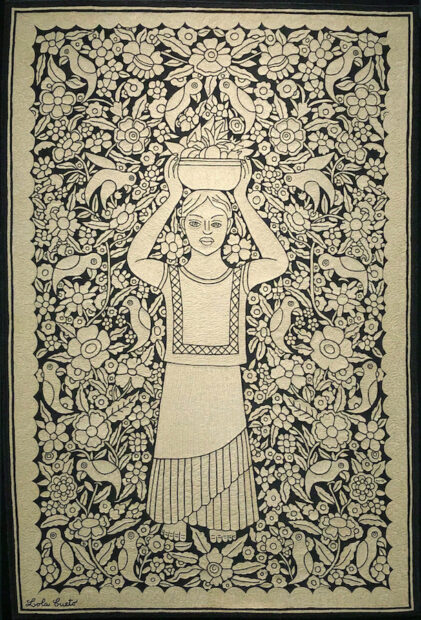

Lola Cueto was one of the first female artists of the Mexican modern era. María Dolores Velázquez Rivas was born in Azcapotzalco in 1897. She was one of the Academia de San Carlos’s first female students when she enrolled in 1909, and was the first to be admitted to a nude drawing course. Cueto’s style was heavily influenced by Mexican popular arts and crafts. Along with her paintings, sculptures, prints, and textiles, she made works in papel picado, crochet, and lacquerware. Cueto was also recognized for her puppets and marionettes, which she used to teach children literacy.

Cueto’s 1928 tapestry Oaxacan Indian Woman — of an indigenous woman in traditional dress surrounded by flowers, animals, cactus, and mountains — fuses two worlds. Though it refers to rural life through the ancient technique of weaving, the piece was made in the cosmopolitan glow of Paris — where Cueto and her sculptor husband Germán Cueto Vidal were living at the time — through a mixture of hand embroidery and a new technology: the sewing machine. Cueto’s tapestries demonstrate the influence of Indigenism, a movement from the 1920s to 1940s in which Latin American artists and intellectuals elevated indigenous ways of life in their works. Over the next years, Cueto’s tapestries were exhibited in Paris, Barcelona, Holland, New York, and around Mexico, where she and her family returned in 1932.

María Izquierdo was arguably the most successful female artist of her day, but her success was hard-won. Born in Jalisco in 1902, Izquierdo made her first artworks in the late 1920s, and was the first female Mexican artist to exhibit her work outside of the country. In addition to her art practice, Izquierdo wrote for magazines and appeared on the radio promoting women’s rights. In her intense, oneiric paintings, women are strong but often agonized, and sometimes shown chained or even decapitated. The tortured paintings reflect Izquierdo’s precarious situation as a divorced mother of three, and the hostility she faced as a female artist in a world dominated by men.

Case in point: Izquierdo’s 1945 mural commission in a Mexico City federal building was cancelled after she’d already begun due to sabotage by Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco, who viewed murals as a masculine medium. But Izquierdo didn’t give up. Castro calls her solitary journey transgressive: “She has a relationship with [the Mexican painter Rufino] Tamayo, but there is no powerful male figure acting as a supporter, protector, or partner. She’s doing this on her own, which comes with much greater risks in that moment in Mexican society.”

These are only three of the many pathbreaking female Mexican artists of this period. While Kahlo’s story is well-known, there’s still much more to explore in the realm of the modern Mexican woman. As Castro says, “A modern Mexican woman can be an artist and is an assertive presence.” It’s worth feeling that presence today.

On view at the Dallas Museum of Art through January 10, 2021

3 comments

Really? We’re still doing ‘female painter” shows?

No, the exhibition features both male and female artists. I just chose to highlight some of the female artists in the show here.

This is an exhibit that you should really see twice, at least, in order to appreciate the era and the painters. Male painters are included and the differences in approach are quite interesting.