Art books! Holiday shoppers! What’s not to love? We have a fine 2020 crop of bound printed matter. Here’s a quick look at three monographs of important individual artists, one document of Texas discovery by a visitor from a distant land, and a detailed survey of a vintage photographic medium.

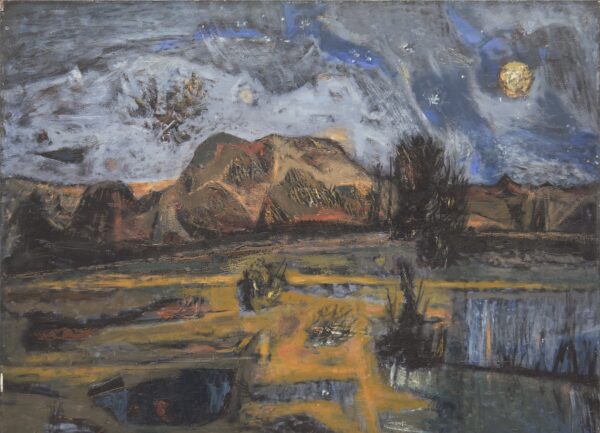

As its title suggests, Texas Made Modern: The Art of Everett Spruce by Shirley Reece-Hughes explores the melding of Modernism with Texas Regionalism in the paintings of Everett Spruce (1908-2002). Reece-Hughes’ book employs a unique four-part structure. First, she contributes an essay illuminating Spruce’s life and work. Then an interview with one of Spruce’s daughters, Alice Spruce Meriwether, is followed by an annotated chronology of the artist’s career compiled by Janelle Montgomery. Finally, a gallery of 39 full-page plates escorts readers through the artist’s development, from his “mysterious, surrealism-imbued landscapes of the 1930s,” to his “bold, expressionist imagery of the 1940s,” and the midcentury works influenced by abstract expressionism.

By 1952, when his painting Desert at Night, was chosen to illustrate a New York Times review of Edna Ferber’s Giant, writes Reece-Hughes, Spruce had become “the most recognized painter in Texas.” A native of Arkansas, where “very early [he] felt an intimacy with nature that has influenced whatever [he] said or wanted to say in painting,” Spruce enrolled in the Dallas Art Institute in 1926 on a scholarship, working as the institution’s janitor to help with expenses. Studying with Olin Travis and Thomas Stell, he later got a job with what became the Dallas Museum of Art, became a member of the Dallas Nine, and in 1940 accepted an offer to teach at the University of Texas at Austin.

A trip to the Big Bend in 1935 deeply impacted the 27 year-old artist. “This problem of expressing more reality than the eye sees has so far dominated my art,” he said in mid-career. The powerful abstract drama that infuses a work like the undated Rio Grande underscores that mission. And while we learn about his artistic influences — from the Italian Primitivists to contemporary aesthetics — we also step into his life. Meriwether’s interview portrays the family’s and the artist’s life on a hilly stretch of 23rd Street in Austin that is now occupied by the LBJ Library and the Briscoe Center. There, she recalls, her artist father would often sit outside sipping Irish whiskey and swapping stories with the likes of J. Frank Dobie and the naturalist Roy Bedichek. She recalled that her father “had the most curious mind of anyone I ever met.”

One of Spruce’s students at UT was the painter Roger Winter. Susie Kalil’s new book, The Art of Roger Winter: Fire and Ice, offers a retrospective of some 80 years of art making. Born in Denison in 1935, Winter grew up in a four-room house “on the wrong side of the tracks” with seven siblings that, for a time, had neither indoor plumbing nor electricity. As a child, Ticonderoga pencil in hand, he compulsively drew faces on Shredded Wheat boxes, finding a certain organic magic in the act. “I didn’t choose art,” he says today. “It chose me.”

When a student sang “Lovesick Blues” in the high-school auditorium, Winter decided he wanted to be a singer. “For me,” he told Kalil, “country music had a wail that wanted to find its own and communicate with something far away.” And storytelling, musing upon the story within the story, has always been at the core of his creativity. (Kalil notes that an accompanying sketch to Winter’s autobiographical montage My Family includes the lyrics to Ernest Tubb’s landmark “Walkin’ the Floor Over You.”) But his father discouraged the path of roadhouse troubadour. And though his brothers cautioned that becoming a visual artist was “one step away from a ballet dancer,” Winter’s parents did buy him a box of oil paints he requested one Christmas from the Sears & Roebuck catalog. And when he hitch-hiked to Austin to attend the University of Texas and first laid eyes on the art department, a new world opened up.

Kalil guides us through Winter’s long productive life, tracking his moves to New York, Dallas (where he taught such artists as John Alexander, David Bates, and Bob Yarber at SMU), England, Maine, New Mexico, Iceland, Bandera County, and elsewhere as she ponders his “eclectic development” through Cubism, Surrealism, Magic Realism, Pop, Constructivism, Primitivism, Realism, Precisionism, Hard Edge, and other idioms that he embraced, combined, and recombined. She writes of the “chaos of life” with its “distortion of memory” and the artist’s plumbing of the human condition in which Winter is able to “be in the moment and yet stand apart.” In 1994, for instance, while living in Maine, having developed homesickness for Texas, he created a trio of Texas Odyssey pieces. Kalil describes them as “a deft melding of formal intelligence and rowdy mysticism that has us questioning the strangeness of our lives.”

Surely, no artist in this neck of the cactus patch ever got more fun out of being a Texan than Bob “Daddy-O” Wade. And when he slipped out of the dance hall late last year, we all felt like the preservation and interpretation of our regional iconography had suddenly become unmoored and was in danger of spinning away from the surface of the earth. Moreover, we lamented the loss of one damn fine hombre.

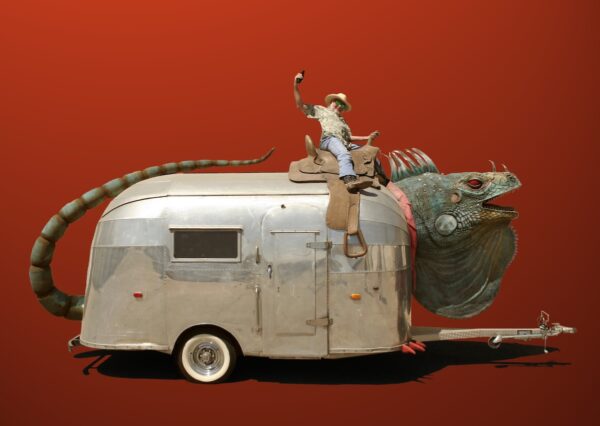

Fortunately, we have this delightful new tome, Daddy-O’s Book of Big-Ass Art by Bob Wade with W. K. Stratton and Rachel Wade. It’s all there, the whole enchilada. You got your world’s-biggest cowboy boots, your giant iguana, your big-ass saxophone, your Kinkymobile “Guv Bug” topped with a big-ass Stetson, your famous big-ass dancing frogs. When I would see those frogs set against the backdrop of a big fat Texas sunset on the roof of Carl’s Corner just north of Hillsboro on my endless treks along I-35, I had a sense that all was right in the world, that I was somehow right where I needed to be. Daddy-O’s work has become a necessary, organic part of the landscape. I beheld his big-ass six-shooter in front of a Del Rio gunshop for years before I knew it was a Bob Wade. A story in the book relates that Dennis Hopper had a similar experience with a Bob Wade work.

Stratton and the Wades invited some 50 or so coolsters, critics, curators, and culture mavens to scribble short reflections about specific works and about the general all-around Daddy-O groove. Cowboy-boots scholar and neon artist Evan Voyles writes about lending his giant neon Chicken Shack sign, salvaged from a long-gone restaurant, to Wade’s 2012 Chicken Ranch Miniature Golf Course installed at Laguna Gloria Art Museum in Austin. Carla Ellard, photography archivist and curator of the Southwestern & Mexican Photography Collection at the Wittliff Collections, comments on Wade’s “reinvention” of vintage photographs of Pancho Villa and other Mexican revolutionaries. Enlarging the historic images and postcards digitally and then “airbrushing transparent layers of acrylic paint over the surface,” Daddy-O also applied this dazzling treatment to pictures of cowgirls, jackelopes, rodeo horny toads, UFOs, and oil wells. Novelist David Marion Wilkinson weighs in on “Daddy-O’s Gallery of Gushers.” Examples of Wade’s reinvented retro-graphs are housed at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the Menil Collection, the New Mexico Museum of Art, and the Prince’s Palace of Monaco.

Perhaps the deepest drill-down into the artwork of Bob Wade in the volume is the essay, “P. T. Barnum Meets Robert Smithson, Or, Claes Oldenburg Speaks with Mark Twain’s Accent” by Jason Mellard, Texas State University professor and editor of Journal of Texas Music History. Moving handily through Wade’s formative years in El Paso/Juarez and his education, Mellard writes, “The … borderlands lent Wade the populist nature of his craft and an eye for vernacular creativity.” At UT Austin, where Daddy-O expanded the hot-roddery that helped fuel his maker-nature in EP, Wade studied with Everett Spruce, William Lester, and Charles Umlauf. Then after grad school in California, with immersion in Bay Area Funk, he rediscovered Texas weird via teaching gigs in Waco and Dallas. In Big D he ran with the Oak Cliff Four, sometimes described as the “Dallas Nine gone gonzo.”

More than any other artist, Wade in the ‘70s, writes Mellard, held a “funhouse mirror” up to Texas eccentricity and excess. Interpreting the Super-American state was in his DNA. “Roy Rogers was Wade’s mother’s cousin, giving Daddy-O early insight into the ways that Western myth and reality played tag with one another.” In a 1977 artist’s book published in the Netherlands, Wade explained that he set out to explicate the big fat state in “ideas and attitudes about scale, culture, myths, symbols, artifacts, history, customs, food, animals, experiences, kitsch, machismo, cross-fertilization, sign systems, tourism, country-western music, the picturesque, boundaries, life and death.” Well okay then. As Mellard says, “Daddy-O is Davy Crockett gone to MoMA.”

Installation view of The Perilous Texas Adventures of Mark Dion, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 2020

The Perilous Texas Adventures of Mark Dion by New York artist Mark Dion and Amon Carter Museum of American Art Curator Margaret C. Adler documents an exhibition presented at the Carter earlier this year. Quirky, fun, and interesting, the show introduced the 19th-century Texas treks of artist Sarah Ann Lillie Hardinge, botanist Charles Wright, artist and ornithologist John James Audobon, and travel writer/landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted… and to Dion’s recent approximate re-creations of their journeys and explorations of his own. Historic documents and artworks accompany biological and plant specimens, along with a marvelous collection of objets de curiosités gathered in the state by the artist.

Installation view of The Perilous Texas Adventures of Mark Dion, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 2020

Even if they cover familiar terrain and demographics, I often feel as though I see this state through a fresh perspective when I read the accounts of travelers who were previously unexposed to its native practices and peculiarities. Dion’s interactions include Texas scientists, artists, Girl Scouts, a Tarot reader, and a Comanche poet. He visits the Museum of Natural & Artificial Ephemerata in Austin, hangs with Justin Parr at his thicketed hideout beside the San Antonio River and the atmospheric ruins of the Hot Wells Hotel, and — in accordance with state law — pops by the King Ranch, the Alamo, the World’s Largest Pecan in Seguin, and Leddy’s in Fort Worth, obtaining at the last the obligatory Resistol chapeau. Responding to our hellish climate like a true Texan, he checks into cranky corner, bellyaching when a gruff Border Patrol checkpoint officer and a grouchy Hueco Tanks park ranger harsh his mellow… and when he yields to local custom and errantly samples the cuisine at Whataburger. Nonetheless, the book is a delight, and the Beaver Cleaver-ish Everyman traveler wrestles our sprawling mess of an historical and cultural entity to a draw.

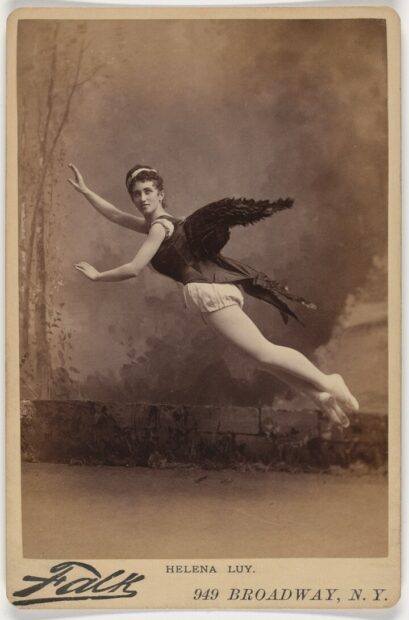

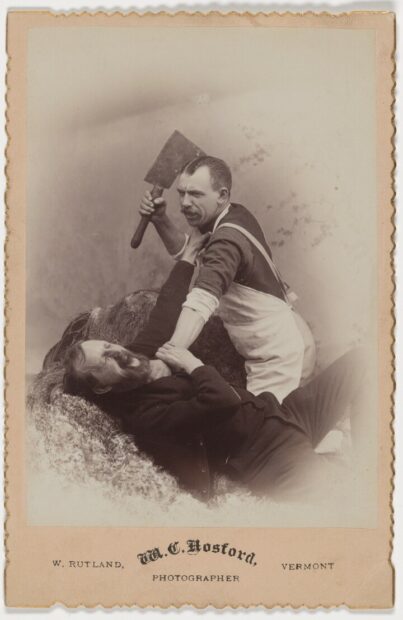

Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography serves as the lavish catalog for another 2020 Amon Carter exhibition. Edited by John Rohrbach, Senior Curator of Photographs at the museum, this lively book and exhibition (which will appear at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art sometime next year) examines an image-making format which, though largely ignored by photography historians, was as wildly popular in the last quarter of the 19th century as selfies are in the 21st. Ubiquitous today in antique malls and curiosity markets, legions of cabinet cards beckon from a gone world, their faces frozen in time, silently hollering that… life happened here. The size of the image, 4 by 5.5 inches, was larger than previous formats, such as the tiny cartes de visite, allowing for more expression and visual information. The cabinet card greatly impacted how people see.

An essay by Erin Pauwels, a Temple University art history professor, explains how the theatricality of images on cabinet cards “opened space for creative experimentation that helped the public to see how photography could be used as tool for art.” Her extensive research on the flamboyant New York photographer Napoleon Sarony reveals that contemporaries considered him the father of artistic photography. Pauwels also posits that he was largely responsible for the birth of American celebrity culture. (That’s right, you can’t blame the existence of the Kardashians on Buffalo Bill.) Partly because of his extensive image-making of actors, Sarony “demonstrated that photography could transform reality as well as reproduce it,” and the portrait process thus became a “performative collaboration.” Moreover, when a dry goods firm ripped off Sarony’s portrait of Oscar Wilde, his 1884 victory in a copyright infringement lawsuit that went all the way to the Supreme Court became “the first legal precedent for recognition of photography as a fine art.”Britt Salvesen, Curator and Department Head of the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department and Prints & Drawings Department at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, covers the nuts-and-bolts of the business of cabinet card photography. Rohrbach’s own scintillating contribution, “Acting Out,” underscores the more active role of those having their portrait made, through the use of props and scenic backdrops and also through the enlarged, in-your-face image size. “Sitters,” he writes, “were not merely there but present.” With cabinet cards, photography’s purpose “had clearly widened dramatically from a basic recording of personhood to a more lighthearted celebration of daily life.” He also shares with Pauwels the notion that the “oddly performed behaviors” seen on cabinet cards embraced both high and low art. The book features more than 100 vintage cabinet cards that reveal the breadth and range of these images, as well as the intriguing Victorian era graphics that adorned the cards’ backs.

These books can all be ordered online. Most sites note that deliveries have been taking a little longer in the season of Covid (and the gumment’s goofy guerrilla war on the post office), but if you’re into art it’s probably a safe assumption that you’re not the wimpy sort who can’t wait a few more days to behold a book. Ordering online, of course, is no match for the tactile experience of acquiring a volume in a brick-and-mortar bookstore or museum shop. Or receiving a book as a gift. I hear that Daddy-O’s book is even available at Austin’s Tarrytown Pharmacy.

More books… . 2019’s The Art of Texas, edited by Ron Tyler, pretty much wraps up the whole shootin’ match. Georgia O’Keeffe’s Wartime Texas Letters by Amy Von Lintel was published this past March. In the arena of Western art we have Making a Hand: The Art of H. D. Bugbee by Michael R. Grauer. SPIRIT: The Art and Life of Jesse Treviño by Anthony Head tells the incredible story of this fine San Antonio artist who learned to paint with his left hand after losing his dominant right hand in Vietnam. Pete Gershon’s COLLISION: The Contemporary Art Scene in Houston, 1972-1985 remains a firecracker, as does Jay Wehnert’s Outsider Art in Texas. I’ve long thought vintage postcards were cool as cultural signifiers, so I’m looking forward to seeing Kenneth Wilson’s SNAPSHOTS AND SHORT NOTES: Images and Messages of Early Twentieth-Century Photo Postcards. Another journey into Houston’s recent past is BOB BILYEU CAMBLIN: An Iconoclast in Houston’s Emerging Art Scene by Sandra Jensen Rowland. A recent-ish title I’ve not seen in the flesh that sounds intriguing is Art_Latin_America: Against the Survey by James Oles.

3 comments

Sure do miss our Daddy-O! Can’t wait to get the book and imagine he’s right there telling me some great new idea.

Daddy-O’s mind was a kaleidoscope of the most essential flavors of Texas, wrapped up in the most fantastic forms that appealed to all of our senses. I had the fortune to assist him on his last project working with the kiddie cars & other larger tube steel fixtures for The Grove, a public art program at Waterside, in Fort Worth. Installed in 2016, this outdoor sculpture celebrates the area’s history and is made from re-purposed amusement rides and playground equipment.

One of the best books I’ve read on Texas Art is MIDCENTURY MODERN ART IN TEXAS by Katie Robinson Edwards.