I met artist Haydee Alonso back in 2017, through the connection of Kerry Doyle, curator and director of the Rubin Center at The University of Texas at El Paso. When Alonso and I sat down to talk, there was an instant chemistry: her warmth and openness ensures easy and fluid conversation, and before you know it, hours have passed. She exudes energy, loves what she does, and loves where she is from.

As an artist, she consistently pushes the barriers of her own practice, moving fluidly between mediums, spaces and ideas, just as she moves fluidly in her space of the border of El Paso and Juárez. Her cities and her region define her personality, as much as they carry the concept of “place” in the fluidity of her work. She is of an area made up of two cities and two countries, and she moves back and forth seamlessly.

Alonso and I recently spent some time in conversation spurred by her latest project, hosted through various Instagram accounts, called The Border Chronicles. Naturally our conversation cycled through her past work, her evolution as an artist, her current interests, and her new jewelry line.

Leslie Moody Castro: You have a very close relationship to your place, specifically your border area of El Paso and Juárez. Can you tell me about that relationship and why it is so close to you and your practice?

Haydee Alonso: I was born in El Paso, Tx and raised in Cd. Juárez. All of my studies, from pre-K to university were in El Paso, and all of my extracurricular activities (summer camp, swimming, karate, etc.) were in Cd. Juárez. I change from English to Spanish and back again, so seamlessly. I alternate from cultures and customs like a modern-day chameleon. One day I’m celebrating the Mexican Independence and the other I’m having Thanksgiving dinner with my father’s side of the family. I have friends on both sides of the border who have actually never met each other because they can’t cross to the other side.

The other side was never really the “other side” for me until I was about 14, but even then it was always about exchange. I didn’t see the border as a division of place, but as a connection. This eventually translated into my work: I began facilitating interactions between two people through objects in a predesigned set of dynamics.

A border has a very definitive purpose: it separates the thing that is not us or it builds a bridge between yours and mine.

LMC: What are some of the ways that this relationship is manifest in your work?

HA: I like to think of myself as an explorer of creative solutions for a divided space. My feet aren’t fixed in a particular dominion, hence creating a state of constant transposition. My work, consciously and unconsciously, deals with the interchange of place. I create tools that encourage interaction. I fill the space between two beings with physical objects. These objects in turn, serve as both a bridge of connect and disconnect. My relationship with the border has led to the continuous quest of understanding the space of the borders themselves by attempting to materialize an intangible exchange.

LMC: Can you describe or give examples of these interactions between people through your objects?

HA: My first attempt at two people interacting through an object was the body of work titled Correct Degrees of Separation. I soldered copper rings of different lengths and sizes which were meant to act as a man-made border; per[des]suading interaction. The smaller the ring, the more distant the interaction; the longer and wide the ring, the more intimate. Correct Degrees of Separation was stimulating the interaction I was hoping for, but the focus was not on the rings at all — it was on the bodies.

This in turn led to the work titled Inter-acting, where I focus on the shape of the actual wires, creating ‘tools’ that serve as both a connection and a barrier. Human relationships change in response to environments. When one is submerged in a culture or place that is not their own, adaptation takes place. Behaviors and interactions shift, stretch, come together and/or detach. What if there is a way to mitigate the transition, or the correct degrees of inter-action? I create tools to help find a surrogate identity that peacefully flows between cultures. Mapping space, and framing gestures.

The “on impulse” interaction encouraged by the wires quickly became of interest to me, and so I created a quiet video of two hands coming together — crossing the boundaries between one person and the other. The video portrays just a few of the many different ways these tools can be used/interpreted.

The video, which I consider part of the series Inter-acting, focuses on the interaction taking place because of the object and not so much on the object itself. Hence the development of my ongoing series Nexus. Interaction is still the driving force of this body of work, but now I focus on the look and feel of its “conductor.”

Rather than using thin wire, which gives the tools a cold and delicate feel, I stabilize the interaction by using a heftier material. I make the exchange, in a way, more reliable. I use bright colors found in my neighborhood of Cd. Juárez, CHIH. in an attempt to rouse the need to engage. I create tools more organic in feel and shape, mimicking the contours of our own bodies, further expanding the possibilities for interaction.

Some of the work in Nexus was commissioned by the magazine Azul Arena and is in collaboration with local photographer Alejandra Aragon. One of her many bodies of work includes a series where she photographs facades and the erosion of time. Crackled paint represents memory, loss, abandonment and violence. I found her work particularly interesting and we both agreed that the conversation between the two could be a visual representation of our reality and our reaction to it. A divided space not only brings a longing to connect, but the repercussions of such often include a destructiveness seen in more ways than one.

Without the willingness to interact, the pieces will not serve their purpose: reciprocity between selves.

LMC: You really toe a line between your practice of art making and your practice as a jeweler. How do the two intersect for you?

HA: My background is in jewelry and metal, but I never really saw myself as a “jeweler.” When I started university, I knew I wanted to study art, and at the time — over 12 years ago — that meant painting. I didn’t realize there were other art forms. I learned about ceramics, sculpture, installation and performance art almost all at once; it was inevitable for me to blend them all into my practice. I wanted to blur the lines and play with pretty much any material I could get my hands on: coffee grounds, tire parts, blinds, grass, cotton, maggots — you name it.

The Metals Department at The University of Texas at El Paso allowed for that creative freedom. Of course I had to learn about stone setting and mechanisms, and other things that were super tedious for me, but I figured out ways to outsmart the assignments by bending the rules without breaking them. I continued my studies as a jeweler, all the way to graduate school, not because I wanted to learn about craft, but because I was intrigued by the concept of body as a site for exploration.

LMC: I like that idea of the “body as a site for exploration.” Can you elaborate a little bit more? Is this in terms of the body as a “canvas” per se or as a medium?

HA: During my studies as a jeweler, we were taught to make rings, bracelets, necklaces and brooches — all of which are activated when worn or seen on the body. It was natural/necessary for me to view the body as a site for exploration. I would develop work in relation to a chest, or finger, or an earlobe, so the body and its contours dictated the direction of my practice very early on in my artistic career. The techniques I learned during my undergraduate studies are still carried on today in my contemporary brand: AYAYAY! Jewelry. I use traditional jewelry-making techniques to create one-of-a-kind, wearable jewelry.

Developing artwork that doesn’t incorporate the body in one way or another seems pointless to me; the work is almost lifeless. So yes, you can say the body became a sort of “canvas.” I’m not sure if I ever saw it or see it as a medium; I see the body more as a conductor — allowing a certain “flow” or connection between each of my series. I’ve never had a predetermined method of creating something, or even a fixed medium. My only constant has been the body. Take for example two of my most recent works, “Morphosis” and “Nexus.” Both are visually very different from each other, yet they both speak about boundaries, interaction, and the adaptation that comes with each. If you take away the body from my work, the pieces would not make any sense.

LMC: Your most recent project is The Border Chronicles, a “choose your own adventure story” via Instagram. How did you come up with this idea? What was the process?

HA: It came about during quarantine. I was the recipient of The Artist Incubator Grant from El Paso for an entirely different proposal, but I had to change it almost entirely due to Covid-19. I didn’t want to take the easy way out and force a project that was never meant for the virtual world, but instead wanted to innovate our current relationship with social media, specifically with the Instagram platform.

My average daily screen time as of today is 4 hours, 25 minutes… . I know. A lot of my day is wasted scrolling and swiping and double tapping. But what if there was a way to be on social media 4 hours and 25 minutes a day without feeling like it was a waste of time, without feeling a sense of regret? Hence the beginning of The Border Chronicles: The Monkey Mix Up, the Sasquatch Anomaly and Pancho Villa’s Final Plea. I created a story within a story, within a story, and so on and so forth.

During my 4 hours and 25 minutes of screen time, I would get lost in Instagram profiles and the tags, hashtags and links that came with each one. I would start with a profile from one of the 1,424 people I follow and 4 hours later, I’d end up in a mukbang ASMR from someone in South Korea who I’ve never heard of. It was this interaction with the platform that I loved and hated all at once. I had spent 4 hours and 25 minutes falling down the rabbit hole that is Instagram.

Then it hit me: what if I were to replicate that exact experience with something creative, and more specifically, with storytelling and images?

LMC: What was the process of coming up with the story in a story in a story? And how did Pancho Villa become a character?

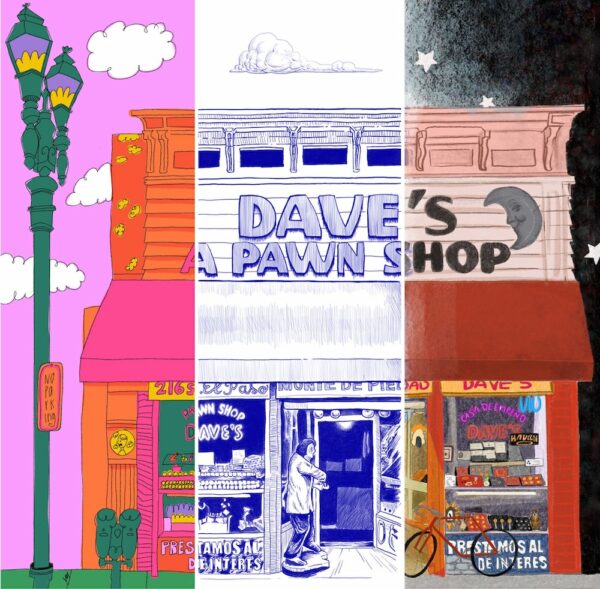

HA: I honestly had no idea how to start, I’ve never really done anything like this before. All I knew was that the story was going to be about a 10-year-old from El Paso who went to Daves A. Pawn Shop to buy a birthday present. I couldn’t physically go to the pawn shop because of Covid, so I visited their instagram profile and started to see all of the bizarre items they carry. The objects that immediately caught my attention were the vial with sasquatch hair and the monkey paw that grants three wishes. It was then that I knew I wanted the user/reader to choose between three different objects. Each object would be the starting point for the rest of the decision making.

Without having figured out the third object, the first thing I did was grab a big sheet of paper and started to draw out a sort of mind map.The rest of the story kind of happened organically. The mind map was a good start, but not the best way to figure out a story within a story within a story, so I scratched it and started doing a story map: bubbles would connect to other bubbles and those bubbles to other bubbles; each bubble representing an Instagram profile. I needed to see the whole story in front of me to make sure the alternate endings made sense or didn’t repeat each other.

And yet I still hadn’t decided on Pancho Villa’s finger — it’s not on the Instagram page and I didn’t know of its existence. I was debating between a shrunken head, a mummy, or one of the many specimens in jars. My partner walked in the studio to find me crouched on all fours, frantically drawing one bubble after the next, writing small notes or doodles for reference. “Why don’t you include Pancho Villa’s finger?” he said.

That was it. I immediately knew Pancho Villa’s trigger finger had to be the third object.

LMC: I’m really interested in how you’re using Instagram as a space of communication and storytelling. You’ve really used the platform as an ‘out of the box’ (square) medium, which it wasn’t designed for, and this is a really subversive gesture. How did you settle on an Instagram format rather than something else?

HA: Instagram is the social media platform that I use the most, though I don’t share my personal life on it very much. I see it more as a space where I can binge watch cultural happenings. From women at detention centers getting unwanted hysterectomies, snippets of KUWTK, Cardi B’s latest rant, Ruth Bader Ginsburg passing, Trump’s latest shenanigans, art calls, etc. It very quickly became my connection to the outside world during quarantine. I get to see my friends’ new baby plants, or the new recipe they finally tried, or their doggies learning new tricks. It was the closest thing I had to hanging out with them so of course it was natural for me to “settle” on an Instagram format.

LMC: The Border Chronicles is also a collaborative project. Can you talk more about those involved?

HA: Yes! It’s important for me to collaborate with creatives in my community. I worked with three illustrators: Mariajose Bujanda, Josias Castorena, and Kytzia Ornelas. All of them have very different styles, and it was important for me that they do so. I want the reader to not only make a decision, thinking about how it will affect the outcome of the story, but also take into consideration the style of each illustrator.

Mariajose and Kytiza live in the border region of Cd. Juárez/El Paso and both studied at the Institute of Architecture, Design and Art (IADA) in Cd. Juárez, while Josias lives in Chihuahua, MX and graduated from The University of Texas at El Paso. I really believe this was a team effort, from Analaura Fuentes, the graphic designer who is also a Cd. Juárez local, to the illustrators and the story itself, which is full of quirky happenings and alternate realities (31 of them).

Each illustrator read the story and interpreted each scene in their own style/color palette. They did everything from character development to layout design, with just a few indications from my part. For example, it was important that the main character, Austen, be nonbinary. I thought it was super interesting how each illustrator’s interpretation of the same scene (with some minor differences between them) were drawn so particularly, for example:

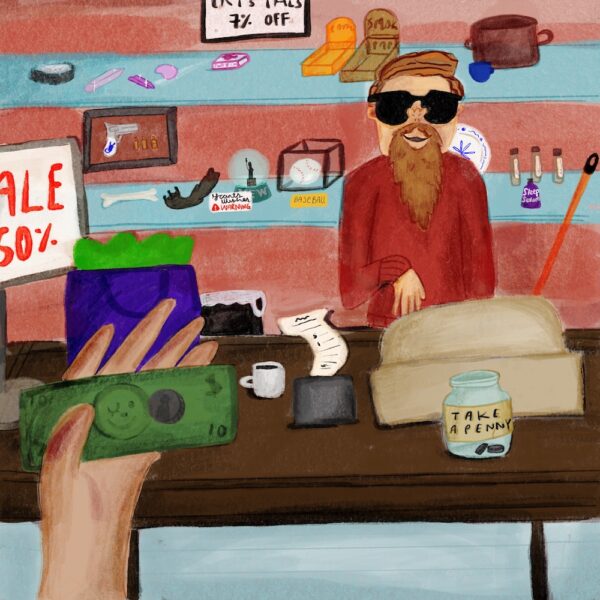

This particular scene is about Austen going into Daves A. Pawn Shop to find a birthday present for a buddy having a birthday party. Austen purchases one of three objects that the reader chooses, exits the shop and runs into Charlie, a buddy that was also on the way to the party. Charlie and Austen talk about their presents for their mutual buddy. Mariajose decides to draw several scenes in a comic book-like layout, while Kytiza focuses on the monetary interaction. Josias illustrates Austen daydreaming about one object more than the others, and Charlie’s present is in the background. This is the variety of focus and layout I was looking for. I created a total of 58 Instagram profiles, all of them with different illustrations and text.

LMC: What is the future of The Border Chronicles? Will there be more stories or outcomes that could potentially connect the outcomes/accounts that you have made?

HA: Wouldn’t that be amazing? A lot of people who have read The Border Chronicles have asked me that same question, and the answer is: everything is a possibility! The funds, provided by Artist Incubator Grant from the Museums of Cultural Affairs Department, have been exhausted and I’m unable to continue to pay the illustrators for their work. This is why I have decided to sell stickers and limited-edition prints that can be found on The Border Chronicles’ Instagram profile.

Once I raise enough money, I can keep creating other alternate endings and, like you said, connect certain outcomes. I feel I’ve only just brushed the tip of what The Border Chronicles can become. Not only that, but how cool would it be to invite other illustrators or animation artists from the border area and have each of them interpret other stories or outcomes?

I say, the more styles, the more outreach.

****

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.