Over the past year, Spencer Evans has been getting to know G. W. Jackson, a brilliant leader who served for 45 years as the founding principal of Corsicana’s first public school for Black students. If you visit Corsicana today, you’ll struggle to find anything that shows what an important figure Jackson was in the city’s history. That’s about to change.

Evans, an artist and professor, was living in Dallas last year when he was approached by the G. W. Jackson Multicultural Society. The organization describes its mission as “creating community collaborations and capturing the rich history and legacy of the African American experience, a vital part of the experience of all Americans.” They wanted Evans to create a bronze statue of Jackson. This will be the first statue dedicated to a Black person in Corsicana’s history.

“Monumentalism has a huge effect on the way we see things as people, and I think we take it for granted,” Evans says. “And that’s where representation really comes into play, it really does matter. Especially when we start to talk about lives that matter, because what is standing up? What will stand the test of time, and what are the things that don’t? What is allowed to be forgotten?”

Evans spent this June in Corsicana sculpting the plasteline model for the statue. The G. W. Jackson Multicultural Society is raising funds to complete the bronze casting and hopes to install the statue in a new park in early 2021. The project is nearing completion after a years-long national reevaluation of public monuments — but this commemoration of G. W. Jackson is more than a decade in the making and long overdue.

****

George Washington Jackson was born in Alabama in 1854. The entry for Jackson in the African American National Biography recounts that he passed the teaching examination at the age of 16 and began a lifelong career as an educator, later graduating from Fisk University. Jackson arrived in Texas in 1876 and was appointed principal of Corsicana’s first public school for Black students in 1882. Over the course of 45 years, the Biography states, “Jackson guided the school from a one-room frame building to one of the most progressive and best-equipped schools” of its kind in the state. One story that gets repeated tells that there were students from Dallas who rode the train 50 miles south just to attend Jackson’s superior school. The school hosted noted speakers, Booker T. Washington among them.

In addition to being a principal, Jackson was an author, founder of a community center, member of the local business league, member of fraternal organizations — the list goes on. In 1924, on the occasion of the opening of a new building, the school was renamed in his honor. G. W. Jackson resigned as principal in 1927 and died in Corsicana on July 21, 1940.

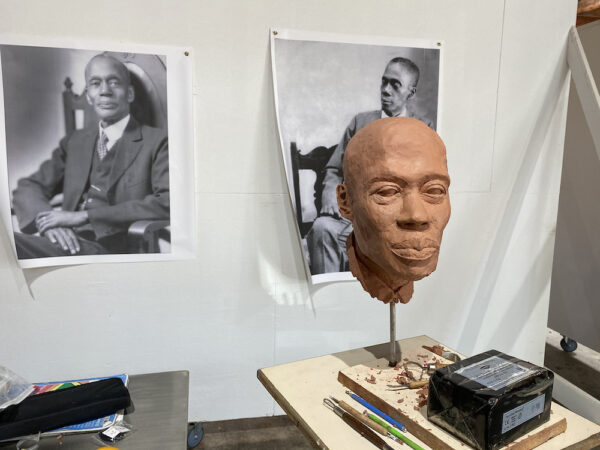

Evans’s sculpture was inspired by the few photographs that exist of G. W. Jackson. Photo: Nancy Rebal

East Fifth Avenue in Corsicana, where the high school stood near North First Street, was renamed G W Jackson Avenue in 2007. The surrounding historically Black neighborhood, east of Business Route 45, is known as the East Side. Apart from the road, there is nearly nothing standing in dedication to this hugely influential figure.

G. W. Jackson High School thrived for decades after Jackson’s tenure. During his time in Corsicana, Spencer Evans listened to alumni share stories about the school.

“And they spoke about different programs, whether it was the track team or the band or the choir or the tennis team and even the seven-time state championship football team that was there,” Evans says. “And so, there’s all of this pride that was spoken of and it was like this own bit of culture that the entire town knows existed, kind of interwoven into the fabric of that town.”

Then, in 1970, the public high schools were integrated and all students enrolled in the fall at a newly-built Corsicana High School. Jackson High was closed.

“It was heart-sickening, heartbreaking,” says Councilwoman Ruby Williams, a lifelong resident of Corsicana and Jackson High alumna. She has served for more than 14 years as the representative for Precinct 2, which includes the East Side neighborhood.

A profoundly important space for the East Side was lost. Some residents tried to repurpose the school buildings. They sought permission from the city to convert the former school into a multipurpose center, or the elementary building into a nursery. Those plans never happened. On March 8, 1971, a fire destroyed the main building of the campus. The city condemned the property and the campus buildings were demolished.

Memories of the school, its accomplishments, and its namesake have been kept alive by loyal alumni. The Jackson Ex-Students Association was formed soon after the school’s closure and holds reunions to this day. The group sponsored a state historical marker recognizing the former location of the school, placed in 1977, and later purchased Bears Field, the former football field.

As the years pass, people do, too. It becomes more important to preserve the legacy of a school that is proudly remembered, but no longer physically exists.

****

Lois Jean Hart was salutatorian of the Jackson High class of 1938. Like G. W. Jackson, her former principal, Hart dedicated her professional life to education. She was a teacher at several schools — including her alma mater, and she was one of the first Black teachers at Corsicana High School — and went on to work for the Texas Education Agency. She retired in the 1980s, but upon returning to Corsicana she “was constantly involved in things for the betterment of our youth, our city,” Williams says. “We just loved her.”

In 2005, Hart purchased the former home of G. W. Jackson at 708 Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd. She envisioned transforming the historic property into a multicultural museum, as she called it, that would honor important figures in Navarro County’s history and Black community. Hart collected memorabilia — books Jackson authored, the speech she gave to her graduating class that Jackson edited — as well as oral histories. She shared her ideas with certain people locally.

“We were an integral part of the city. There were so many great things that happened through the school that were not recognized by the city,” Williams says. “And it was devastating to see that nothing was being done to showcase the legacy of the G. W. Jackson High School because it was a great school. So we were trying to figure out what we could do.”

When Hart’s health declined, her sister Gwen Chance was called on to step in.

“The city of Corsicana contacted me and shared with me what she was doing because she kept them all involved, and wondered what I wanted to do,” Chance says.

Chance is Lois Hart’s half-sister. She was raised in Dallas and has lived and worked in Austin for many years. Although she wasn’t from Corsicana, she recognized the project’s importance. With her family’s blessing and the city’s encouragement, she decided to continue her sister’s mission.

In 2008, a committee was formed to oversee the restoration of the Jackson home. Led by Chance, the committee included people of diverse backgrounds interested in saving the historic building. This group evolved into the G. W. Jackson Multicultural Society, a nonprofit organization.

Lois Hart passed away the following year. Her devotion to preserving history and her extraordinary vision set a series of events in motion that would take more than a decade to culminate.

Originally, the group hoped to convert the Jackson homestead into a museum, as Hart planned. With the city’s help, they got a grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation to produce a structural report on the home.

“So after we got the report that it had a lot of potential to be restored … we hired a contractor, contracted with a company local there that had come recommended,” Chance says. “And then when they began to level the home, it just kind of fell apart. They did not do us well.”

The Corsicana Daily Sun reported at the time that “before a new concrete foundation could be poured, it became evident that the work to stabilize the house hadn’t been sufficient and it began to sag alarmingly.” The condition of the building was worsened to a degree that, in 2012, the organization decided to demolish the house.

For the bare plot of land, the Multicultural Society began to envision new possibilities. A park would be more open to the community and easier to maintain.

Then another idea occurred to them.

Starting in 2011, bronze statues dedicated to important people or industries in Corsicana’s history began appearing around town. There are at least 10 of these statues today, mostly privately funded — they can cost tens of thousands of dollars to produce — and installed in the historic downtown with the city’s approval. Those and a few older works make up the Corsicana Bronze Statue Tour. They honor oil field workers (the Texas oil boom has origins in Corsicana) and fruitcake bakers (Collin Street Bakery originated there, too), but none honor a Black historical figure and none are located on the East Side.

Nancy Rebal is an artist and creator of one of the city’s bronze statues, dedicated to Wolf Brand Chili. After the unveiling of her work in 2018, she was approached by Joe Brooks, a member of the Multicultural Society’s advisory board, about a statue for G. W. Jackson. Although Rebal is now based in Corsicana, she lived and exhibited work in Dallas for many years. She joined the group’s advisory board and started asking acquaintances at galleries about artists who might be a fit for the project. Her research led the group to Spencer Evans.

They were drawn to the expressiveness of the figures in Evans’ work. His paintings and drawings have what he calls a tension between some portions that are realistic and others that are abstract. His figures have detailed faces, focusing the viewer’s attention. The bodies are frequently in active poses, emphasized by gestural brushstrokes or sketch-like markings. That his work is not just representational, but dramatic, made Evans an ideal candidate for portraying a historical figure as storied as G. W. Jackson.

Spencer Evans was born and raised in Houston. He completed his undergraduate degree in Missouri, returned to Texas, and obtained his M.F.A. from the University of Texas at Arlington in 2017. When the Multicultural Society contacted him last August, Evans was preparing to move to start a professorship at the Rhode Island School of Design.

The G. W. Jackson commission would be his first large-scale, full-figure sculpture, although he had previously created small bronzes. Evans is primarily a painter, but studied foundry while at UTA. He said he became intrigued by the ability of sculpture to make viewers approach a figurative work less like an object, and more as if they were sharing space with an actual person.

Before committing to the project, Evans spent a day in Corsicana learning about the city. He said at one point he met with Councilwoman Williams, and she spoke to him about how meaningful it would be to see this statue realized on the East Side.

“I decided that I had to do this,” Evans says. “I really wanted to do this, and became kind of obsessed with it from there.”

The project resonated on a personal level for Evans. He is a former high school teacher. He taught algebra and art in Houston before going to graduate school, an experience he said fundamentally changed him. He admired Jackson’s commitment to teaching at an impressively young age.

Evans is also the son of a principal, something he said connected him to G. W. Jackson and gave him an understanding of the strength and devotion “it takes to be a Black principal of a Black school in Texas, in a district that doesn’t really work to make sure that those types of schools are thriving.” He recognized certain qualities that he observed in his father in G. W. Jackson — versatile leaders who not only educate their students, but also nurture pride in their identity. In addition to research, Evans drew from his personal knowledge to realize the monument.

From Rhode Island, Evans stayed in touch with Nancy Rebal, sending pictures of sketches and maquettes for the Multicultural Society’s approval. This back-and-forth over several months informed the development of the sculpture.

This summer, it was finally time for Evans to return to Corsicana. Rebal and her husband David Searcy prepared her downtown studio for Evans to work in.

Evans completed the plasteline sculpture in 19 days. “He did it beautifully, and took care of every detail that he wanted to do. It wasn’t a rush at all,” Rebal says. She took daily photos and videos of Evans’ progress in the studio.

He began with the head. As in his paintings, he devoted the most precision to facial details, recreating Jackson’s likeness based on the few existing photographs of the principal. Gwen Chance also brought to the studio a painting of G. W. Jackson by Walter F. Cotton, a former principal of Jackson High School, historian, and artist. Chance said Lois Hart originally commissioned the painting for a school program, and after finding it in storage she had it restored and framed.

At the same time Evans sculpted the head, he worked with Searcy to create the armature for the body.

The face may be based on photographs, but the pose is Evans’ invention. It was important that the monument for Jackson be distinct from any statue downtown. Jackson is seated with a book in one hand — The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois — and the other hand outstretched. His slightly twisting body and textured suit convey the same motion that is essential to Evans’ paintings. Evans wanted Jackson not to appear suspended in the past, but active in the present, literally reaching out to future generations.

Rebal’s studio has windows facing Beaton Street. For several weeks, people could walk by and see Evans at work. “People were excited by it,” Rebal says. “You see bronze statues all the time, but you don’t see somebody making one.”

Although the Covid-19 pandemic prevented the group from hosting some of the events they hoped for, Evans occasionally took socially-distanced visits. “That made it even more special, that he was so comfortable with that approach,” Chance says. “The fact that he would talk about what he was doing, how he was feeling and seeing … and the sharing of that with those of us who would watch his work.”

Evans says he spent 10, sometimes 12 hours in the studio most days, completely absorbed by his work. “There’d be times when I was thinking I was done for the day and I would look back at that statue as if he was saying ‘No, come back, there’s still this that needs to be done,’” Evans says. “A man that I’ve never known … that I feel like I know like family almost. It was a very spiritual experience.”

“He got so into this person. It was really beautiful,” Rebal says. “He brought him back to life.”

The organization is currently fundraising for the bronze casting of Evans’ sculpture, and the creation of the G. W. Jackson Multicultural Society Legacy Park. Once completed, they plan to host events, concerts, picnics, and other programs there. It will be a space for people from Corsicana and beyond to spend time and learn more about the great educator who once called that land home.

“And I’m hoping it will be a beacon of light to the neighborhood and to the city of Corsicana as a whole,” Williams says.

For Gwen Chance, it’s hard to express what it will mean to see the project completed. The park and statue will conclude a 12-year undertaking that required long drives to Corsicana, building trust with local residents, and navigating many opinions at different phases of the project about how to move forward. But now, she says, people even ask her: “Why don’t you move to Corsicana?”

Her sister Lois Hart’s vision is closer than ever to becoming a reality. “I will be so excited that it has culminated and is now a part of the fabric of the city of Corsicana,” Chance says.

The organization is also working on building a website; a landscape architect is drafting designs for the park; and the artifacts in storage might eventually be displayed. But that will all happen in the future.

Spencer Evans calls it “a blessing and a privilege to be called upon” to create this monument in his home state. He hopes that the statue is a catalyst for more — more investment in the East Side, more monuments that restore honor to Black Americans whose achievements have been erased.

“I think about children, the next generation growing up around a statue that looks like them in some kind of way. And that does something to our sense of identity,” Evans says. “That’s something I think is amazing and beautiful for Corsicana, especially the East Side, but I think for everyone. If you think about the younger generation of other kids, who aren’t Black, who are seeing a sculpture of a Black person there… . It doesn’t have to be a question of who matters and who doesn’t.”

****

Donations of any amount can be made via PayPal (paypal.me/gjacksonsociety) or sent to: GW JACKSON Multicultural Society, PO BOX 1026, Corsicana, TX, 75151-1026

3 comments

Excellent article on the GW Jackson multicultural museum in corsicana and all the special work that has been put into it and the dreams.

This is amazing! I have several relatives that are proud graduates of this school. A great uncle was a principal in the later years, Ezra Carroll. Can’t wait to see this. Excellent work!

This is beautiful!