Arthur Peña, Attempt 172.

When I think of neon, I think of Turin, Italy. I spent a month there earlier this year, just before Covid-19 spread throughout the region. I’d flown in late one night and took a cab into the city. What I noticed from the car window — besides Turin’s tall, arched porticos and long, straight avenues — was all the neon everywhere. Neon signs for Chinese restaurants, coffee joints, and sketchy hotels, one of which I’d end up in later that night, filled the old town like noisy, nocturnal chatter.

Turin sits at the foot of the Alps, and around 6 pm the mountains go hazy and the sky turns creamy peach. That’s when the city’s Baroque, Rococo, and Neoclassical facades light up pink, blue, and yellow. Wiry letters blurt out curt messages to the passersby: CAFFE, HOTEL DELLAMORE RESORT, SNACK DRINK. Curiously, most signs looked like they’ve been there, unchanged, for decades. Signs even light up places that have long gone out of business, so that you might walk to the end of a block in search of something that, upon arrival, simply doesn’t exist.

Arthur Peña, Attempt 175

Neon is an odorless, colorless, inert gas. It is obtained by distilling liquid air, and glows through an unlikely fusion of electricity, gas, and light. Neon is pure evanescence. So it’s an odd experience to view Arthur Peña’s paintings, which seem to press neon’s ephemeral effects into oil on canvas. In Waiting for Something to Lose at Nancy Littlejohn Fine Art in Houston, Peña’s paintings of mysterious texts and fragmented human appendages illuminate a strange, dark world.

Like neon itself, Peña’s paintings have an otherworldly quality. Beyond his unsettling imagery, Peña’s technique is intriguing and confounding in equal parts. In his paintings, subtle, airbrush-like gradients play against turbid, painterly strokes. The textures and treatment simultaneously suggest layers and flatness, vibrance and opacity. Peña loves to paint, and his luminous surfaces showcase his ample skill. But really, the neon visuals are a subterfuge. His perplexing light effects draw viewers in long enough, in the artist’s words, to “sit with the imagery of what the work is really about.” And for Peña that means the anxiety of being alive, a decidedly less-glowing motif.

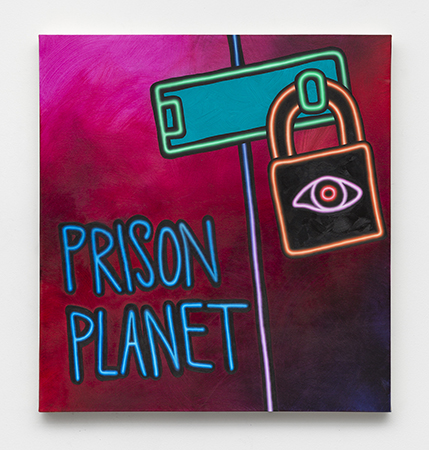

Peña’s canvasses emit a sense of danger. Disembodied hands figure heavily in the work, and their cryptic gestures imply that something menacing is about to happen. We see hands writing, checking a watch, holding a letter, crossed across a bare chest, and tied behind a nude back with thick yellow rope. Peña views the body as a site of subjective and objective violence, and physical and psychological vulnerability charge his works. “The world we occupy is a horror movie,” the artist told me, which rings especially true this year. Even though the works in Peña’s current exhibition were all made in 2019, they feel sharply prophetic of our grim, lockdown days, especially Attempt 186, with its thick door lock, wide eye, and the words “PRISON PLANET” emblazoned across the painting’s left side.

Attempt 186

This isn’t the first time that Peña has seen the outside world as a threat. Growing up in the Oak Cliff neighborhood of Dallas, the artist witnessed the toll of gang violence in the area. When I asked Peña why the violence in his paintings doesn’t reference the police brutality, domestic terror, and other acts of cruelty that occur on a daily basis in this country, he replied this way:

“Suffering is timeless. It’s the thing that binds us all, really. I understood early on because of where I grew up the heartbreak of violence, and the sense of oppression and helplessness. We really all know what it’s like to hurt. Happiness is subjective. But there’s a baseline for the hurt when someone leaves us, or feeling a sense that things aren’t going your way and feeling lost. So I want these images to touch on that sense that we’re all in this together.”

Peña considers his paintings to be mirrors of his personal life and artistic practice at any given moment. “Every painting is a turning point,” he told me. Each of his works is titled an “Attempt” and assigned a chronological number. Conceptualizing his work as attempts grants Peña room to change and grow, but is also a poignantly clear sign that, in the painter’s words, “I tried.” Peña’s modest titles also reflect the precarity of making and the precarity of life. “They’re going to be attempts until I die,” Peña explained. “That’s the work.”

Neon naturally glows red-orange when excited electrically, though its color can be manipulated. Morris W. Travers, one of the two British scientists who discovered neon in 1898, wrote, “The blaze of crimson light from the tube told its own story and was a sight to dwell upon and never forget.” Peña’s paintings are enticing to look at but difficult to digest. They stay with us for a long time, too.

Arthur Peña: Waiting for Something to Lose is on view at Nancy Littlejohn Fine Art in Houston through November 28, 2020.

1 comment

I think his works are a reminder that despite the ephemeral nature of neon, suffering is a universal experience that connects us all; I also appreciate the thought-provoking examination of the symbolism behind neon signs and the evocative power of art to capture universal human experiences.