I remember when Nicole Tersigni’s thread of portraiture-based mansplaining memes started popping up in my Twitter feed last year. I laughed until I cried.

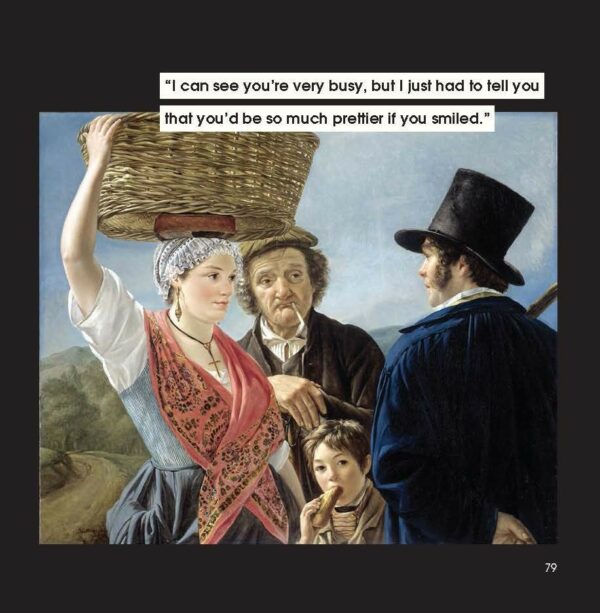

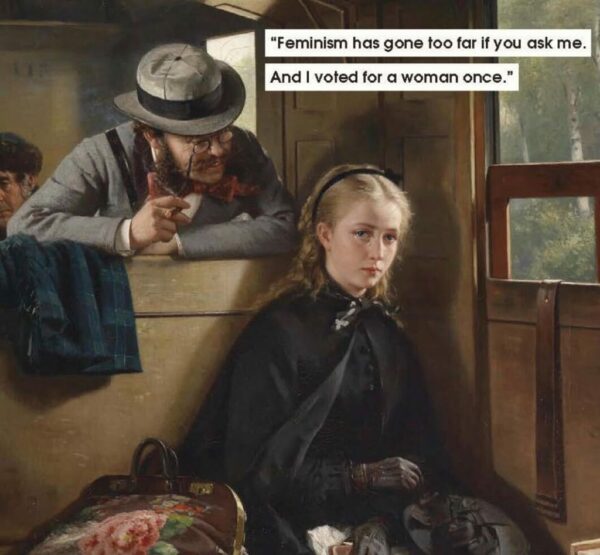

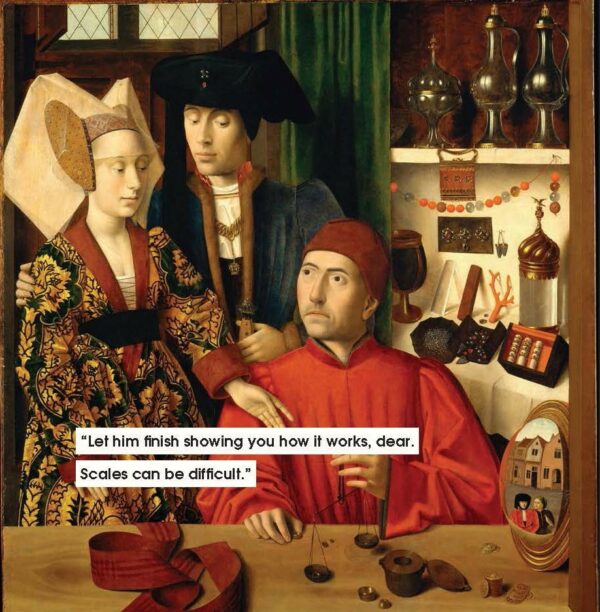

In the thread, Tersigni had taken classic works of Western art from the last six centuries and captioned them with imagined conversation between the paintings’ subjects. Specifically, she crafted dialogue with men in the paintings offering unsolicited, unwelcome, and generally unwanted opinions to women. (“You would be so much prettier if you smiled.”) The entire comedic genius of it all came from the poker-faced mansplaining of Tersigni’s captions — the annoying ridiculousness of “Let me explain your lived experience to you.” (He says: “Now, when you’re riding a horse, you need to make sure that you keep a good grip on the reins.” She thinks: “These are my horses.”)

The original Twitter thread was one part performance art, one part satire, and one part exasperated disgust at having your own joke or experience explained back by a “concerned guy” on social media for the umpty-bajillionth time. For those of us who wanted more, that more has arrived. The thread has been expanded into a short book, Men to Avoid in Art and Life (Chronicle Books), with more than 90 captioned images, and a forward by the comedian Jen Kirkman. It’s brilliant. I laughed until I cried — again.

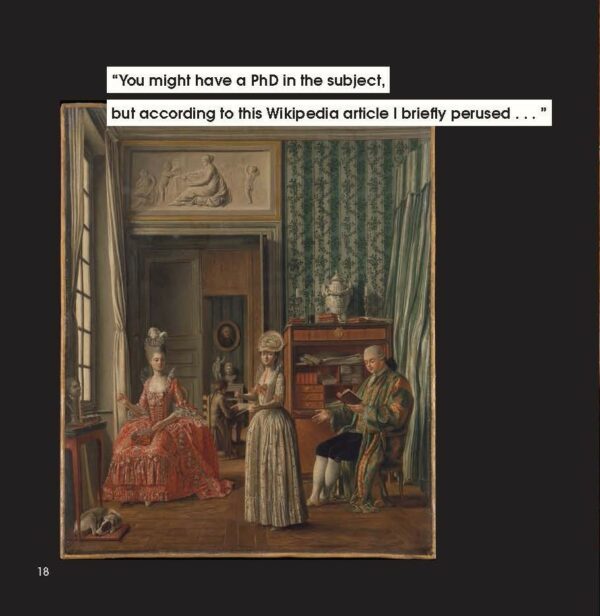

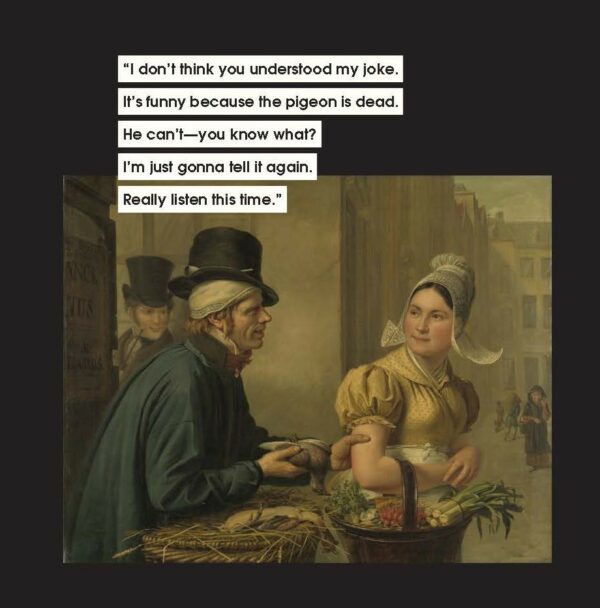

While meming classic works of art isn’t new, the volume, scope, and caustic wit of Tersigni’s work brings a deepening dimension to the genre. Portrait by portrait, she manages to vivisect the mansplainers of the world — specifically, those she terms concern trolls, sexperts, comedians, and patronizers. The book is a catalog of men, from those who insist that their jokes are funny — and you simply lack the wherewithal to properly appreciate their comedic genius — to men who weaponize women’s feelings to gaslight them for their own petty gain. (“Get it? No? Really listen closely to the joke this time;” “I can’t talk to you when you’re hysterical.”) Inspiration for the captioned dialogue, I would venture to guess, draws from the wellspring of experience acquired by simply being a woman (who uses Twitter).

It’s impossible to pick a favorite “man to avoid” meme, but two stand out. The first is the gentleman in Berthold Woltze’s The Irritating Gentleman (1874), a middle-aged man in spectacles, pink bowtie, and an aggressive set of muttonchops; he’s carelessly dangling a lit cigar over a bench and he leans down to blithely chat with a young woman who seems to want to will herself out of the painting. “There probably just weren’t any qualified women for the job,” Tersigni’s caption deadpans.

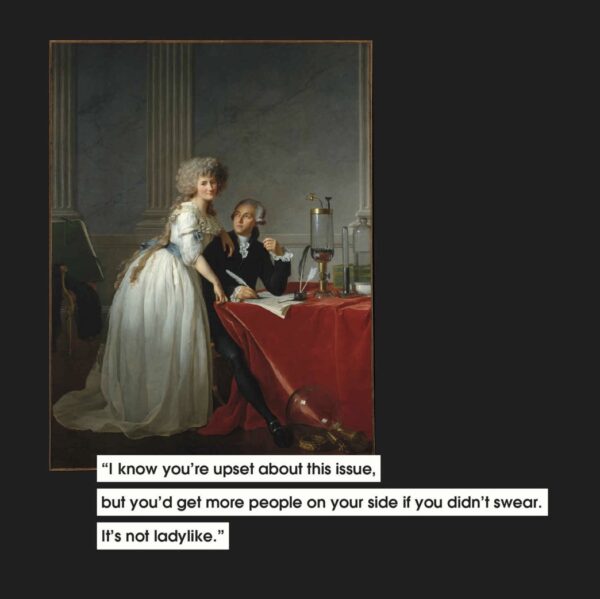

Although Tersigni doesn’t dig into any of the works of art in any historical detail — she lets the original work serve as a backdrop — the context that surrounds Jacques-Louis David’s portrait Antoine Laurent Lavoisier and His Wife (1788) resonates with the theme of the book on several levels. This is the second portrait meme that really stands out in the collection.

Although Tersigni doesn’t dig into any of the works of art in any historical detail — she lets the original work serve as a backdrop — the context that surrounds Jacques-Louis David’s portrait Antoine Laurent Lavoisier and His Wife (1788) resonates with the theme of the book on several levels. This is the second portrait meme that really stands out in the collection.

Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794) was a brilliant chemist, credited with the discovery of oxygen and the chemical composition of water. He was married to Marie-Anne Paulze (1758-1836), who collaborated with Lavoisier in his laboratory work — she was properly trained in the chemical sciences of the time and a scientist in her own right. Her illustrations of Lavoisier’s experimental apparatuses were invaluable; she translated scientific papers from English in French for Lavoisier to read, and actively participated in laboratory experiments. Lavoisier was eventually guillotined during the Reign of Terror in 1794. After his death, Marie-Anne Paulze Lavoisier organized for his final scientific work to be published in three volumes, ensuring his scientific legacy. Her work and contributions, however, remain largely forgotten.

All that, and Marie-Anne Paulze Lavoisier doesn’t even get her name in David’s portrait title. (Tersigni captioned the portrait with: “I know you’re upset about this issue, but you’d get more people on your side if you didn’t swear. It’s not ladylike.”) And history, it would seem, hasn’t quite finished cropping her out of Lavoisier’s story. Antoine Lavoisier’s Wikipedia page features David’s portrait to illustrate Lavoisier. However, Marie-Anne is literally cropped out of the image offering readers only a close-up of Lavoisier’s face. If you look carefully, you can see part of Marie-Anne’s hand and one of her hair curls. Incidentally, her own Wikipedia entry features the same portrait — but uncropped to include her husband. Irony is dead.

Men to Avoid in Art and Life has successfully moved beyond its early days as a viral thread on Twitter. It is book for every woman who has endured any conversation that begins with “But not all men;” “Well, actually…;” or had her own lived experiences explained to her either online or by her brother-in-law over Thanksgiving dinner. Thanks to millennia of sexism, Tersigni will never want for material. More Men To Avoid in Art and Life, perhaps — should she opt for a sequel.

‘Men to Avoid in Art and Life’ by Nicole Tersigni (Chronicle Books) is available here and here.