The Art Museum of Southeast Texas in Beaumont seems to gravitate toward work that has an obsessive aesthetic— repetitive gestures, detailed processes, and a postmodern immersion in a fast-paced, technologically-driven (and anxiety-ridden) world. An exhibition in 2011, Obsessive Worlds, as well as collecting tendencies for artists such as Mary McCleary, Al Souza and Paul Manes, reflect the museum’s appreciation for works meticulously constructed with mixed media. The museum’s current exhibitions of two Texas contemporary artists reiterates this love for detailed work and painstaking methods.

The first gallery hosts a survey of works from Patrick Turk, titled Higher Planes, includes Turk’s multimedia sculptures and sculptural collages. Shapeshifter (2019) is a six-foot tall, multi-hued bipedal creature that rotates on a low platform. With cameras installed in its eyeholes, two projectors livestream the camera feeds on walls on both sides of the sculpture. The projected images (sometimes of you, the viewer) appear warped by a fisheye camera view and a swirl effect, resulting in a dizzying optical experience. The human-sized, non-human creature sets the tone for the show’s exploration of social and scientific themes concerning humanity, and a creative inquiry into the next stage of our evolution.

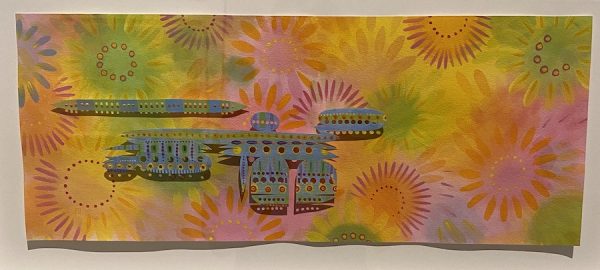

Close-up of Turk’s Time Travel Research Institute Presents: 360,000,000 B.C. – 65,000,000 B.C. Image by author.

The lighting in the gallery is dark, and dramatizes the illuminations from a series of shadow boxes called The Time Travel Research Institute Presents… . These boxes are fronted by a black layer with circle cutouts for lenses that emit light as well as reveal collages within, with images cut from magazine and textbooks recounting imaginary time travels to the past, beginning in 360,000,0000 B.C.E. with the Big Bang and single-cell organisms, and ending with glimpses into the future through the year 3700, when humans have merged with technology. The series emulates subject matter and anthropological displays at natural history museums, and proposes an alternative epistemology to how the history of mankind, in addition to biological processes, can be understood. It likely isn’t a coincidence that the acronym of the series is “TTRIP” — viewing the collages through the circular fisheye peep holes provides the viewer a consciousness-expanding reorganization of vaguely familiar topics from history and science classes. The more figurative collages particularly dazzle in these boxes, demanding the viewer spend time shifting from peephole to peephole to check out the dense collection of images. The Time Travel Research Institute Presents: 1804- 1869 contains pop culture recollections of the Wild West, with gunslinging cowboys, but also images of indigenous people in customary dress that could have been clipped from the pages of a vintage National Geographic. Other holes reveal anatomical illustrations of the human body, a theme repeated throughout all of the collages in the show.

Wall with Turk’s six pentagon-shaped sculptural collages. Center- The Multipliers (2016); Top center- The Keeper (2016); Right center- The Sentinel (2016); Right bottom- Dust (2016); Left bottom- Beguiled (2016); Left center- The Cleaving. Photo by author.

Turk’s Dust (2016). Collection of Rob Clark and Jerry Thacker. Photo provided by the Art Museum of Southeast Texas.

The rest of the exhibition is Turk’s sculptural collages — works that hang off the wall but are made three-dimensional by Turk’s painstaking layering of two-dimensional paper clippings, shaped to form multidimensional works. One wall of the gallery contains a large pentagon shape formed by six individual pentagon sculptural collages. While the collages inside the lit display boxes are layered, the pentagon sculptures take the cut-and-paste process to its extreme limits, twisting and intertwining interconnecting parts which results in a maximal optical experience. Two other collages on the adjacent wall do the same: The Superorganism: Concrescence (2012) and The Superorganism: Entropy (2012). While the Time Travel Research Institute Presents… series presents particular timeframes within human history, these two Superorganism sculptural collages posit the beginning and end of human evolution into a “superorganism” — an individual entity composed of not only mankind but also the flora and fauna of this planet.

Walking into Kana Harada’s exhibition Celestial Garden from Turk’s Higher Planes is like emerging from a dark movie theater into the daylight. The multilayered and metaphysical questions that Turk’s work demands are traded for meditation and wonder in Harada’s space. Harada’s ethereal hanging sculptures formed from found tree branches and intricately cut paper and foam move gently within the space, emulating faint breezes that sway the flowers and trees outside the museum. Cotton Candy Tree (2012) and Dance With Me (2011) float from fishing line and cast subtle shadows on the walls. Three benches surround Dance With Me (2011), encouraging viewers to sit and meditate with the work.

The largest work in the show, Goddess of the Dawn (2006), is particularly impressive due to its scale and its details. Prior to reading the title of this work, I interpreted the sculpture as a sort of “castle in the sky” — an imaginary floating world hidden in the clouds. But its title, Goddess, shifts its presence to that of an entity reaching out to wake up the world with her promise of sunrise. Another floating sculpture, Portrait (2009), appears as a white willowy branch that rotates slowly on its fishing line, with a mirror attached that reflects the viewer. Harada’s emulations of the textures and pliability of nature in paper and foam seamlessly blends with her mixed-media approach of using found branches to anchor her materials.

Harada’s Where We Always Meet, 2017, Collection of George Morton & Karol Howard. Photo provided by the Art Museum of Southeast Texas.

Celestial Gardens includes a selection of pastel and white watercolor works layered with pasted paper and foam cut outs. In Cheer (2015), Harada layers small paper designs that mimic floral forms and extraterrestrial figures on top of watercolor tessellations of circular arrangements. Earthly shapes and UFO silhouettes appear in other watercolors here, including Odyssey (2017) and Where We Always Meet (2017). The mélange of the worldly and otherworldly in both Harada’s watercolors and sculptures gives viewers a meditative escape from the anxieties of a quarantine state.

Harada captures the peacefulness of the Fuji Sanctuary at Mount Fuji, near her hometown of Tokyo. The color palette of her watercolors and paper sculptures offer a more mellow viewing experience than Turk, but similarly echoes a time-consuming process of cutting and pasting. Outside of the main exhibitions, AMSET highlights artists in its permanent collection who are celebrated for their “obsessive tendencies” in the production of their work. Included here are Texas art veterans Mary McCleary and Al Souza. McCleary’s I Fled Him Down the Nights and Down the Days functions as a visual riddle akin to an I Spy book, with unlikely objects adhered to the two-dimensional surface forming a complex figurative composition. Next to McCleary’s work, Souza’s Ratoo Barada Nictoe (2003) is circle-shaped piece constructed from snippets of dozens of completed puzzles, resulting in a dazzling wheel of colors and forms.

Turk’s Higher Planes, with its lush and excessive collage work, offers musings on the clusters of cells, foliage and animal life that make up the world, and it does so through Turk’s obsessive aesthetic. This obsessive approach is present in Harada’s Celestial Gardens, but with a more introspective and relaxing effect on viewers — much needed during months of uncertainty under quarantine.

On view through September 13, 2020 at the Art Museum of Southeast Texas, Beaumont. The museum is open, with COVID-19 protocols in place.