In her recent show at Talley Dunn Gallery in Dallas, which unfortunately spent most of its run shuttered, Houston’s Francesca Fuchs offered us (in the form of paintings and mugs) meditations on paintings, mugs, and other artifacts. There is good video footage of the exhibition available, but since the work traffics in presence, I’d like to supplement that footage with some notes taken in the flesh.

The gallery’s large main rooms held more than a dozen easel-sized canvases and a number of ceramic objects on a rough wooden cabinet in the center of one room, as well as a handful accompanying the paintings in ones and twos on a wall shelf or pedestal. These ceramic mugs and vases are also painted with oils to depict their mass-produced subjects, inflecting the room with a Disney World sense of hyperreality. As with much of Fuchs’ work, what seems at first to be direct and simple here sits delicately in a problematized web of representational quotes.

Fuchs’ past bodies of work have included “paintings of paintings,” images of Christmas trees, and objects from her late father’s desk. This collection pulls from a wide array of cultural objects both flat and sculptural, and across many eras and cultural hierarchies. All of her compositions are more or less centered. Those of wall-based artifacts zoom out enough to include matting, frame, slivers of wall, slight reveals, and shadows. The freestanding objects are treated like straightforward still lifes, as with the painting Knee, which focuses on an amorphous fragment of stone or plaster with a bumpy seam down the center of it. The chunk of rubble leans back and to the right, threatening to tip. But as a 2D object it gets righted and balances on its drop shadow. The hazy, warm and cool grays that melt into the space around it ground all the information into surface. Everything is made of the same matter and light. This is elemental painting.

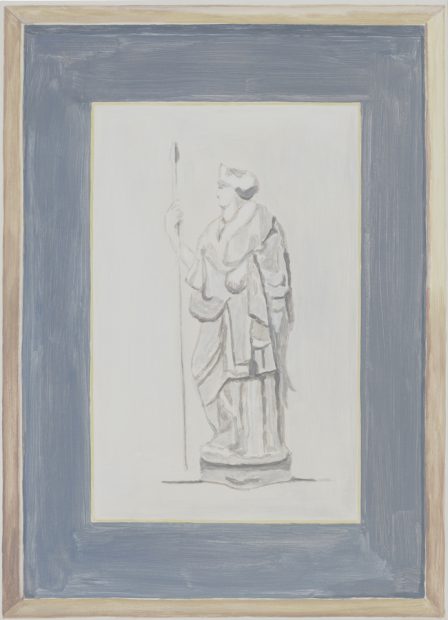

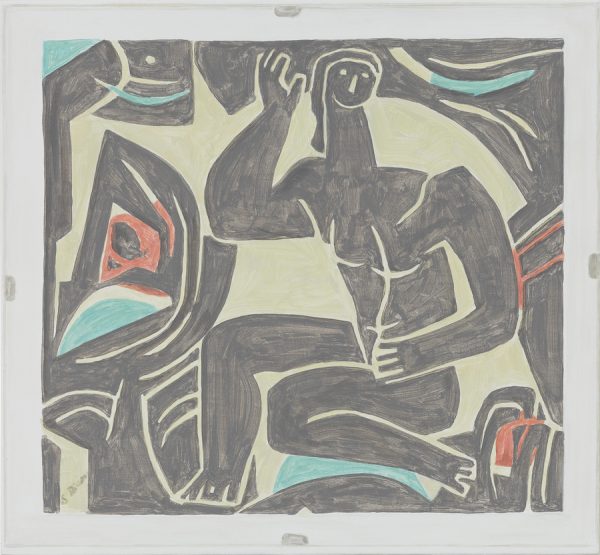

Some works get more complex adding more color, more iconicity, more potential signifiers or layers of representation. Hera tightly crops a framed and matted image of an ancient statue. Biese looks to be a thin, washy version of a modernist woodcut print, complete with mounting tabs at the edge of the picture plane. Proof that her subject matter is not the picture in the window, but something of the window itself — the space and texture of vision.

Ladybug studies a painted rock, itself a sort of crude nature study or lesson in copying. And perhaps the most fraught painted object here isn’t from any art canon, but a recent looking protest sign with the words “THE TRUTH MATTERS” starkly scrawled in red. Their resounding through line is the mute visual sense worked out in them as surfaces.

Fuchs’ paintings seem to loosely fumble around with the concept of documentation. But none of these are mere “copies”; colors are desaturated, the contrast is lowered, information is abbreviated with her unfussy brushwork. Her versions are more airy and soft, built out of gauzy dull blues, yellowish grays, ochres, and browns so slight they barely register.

Horserider hits all of these buttons. It’s an iconic and recognizable image, yet translated into such thin and essential configurations of shape that it exists as a completely new thing. It sits in between something copied and something original. I found myself standing in front of it wondering what it is I’m seeing, what kind of entity. That’s a very fertile place.

The ceramics on display are really just paintings wrapped around stoneware, though they seem a bit sneakier than the canvases. They are like a Morandi still life that we enter by way of the painting meeting us out in the world.

They are slightly cruder versions of familiar quotidian mugs and vases, textured with brush strokes in oil. They study the bright colors and shapes of mass-produced vessels, and conjure up workaday diners, Pier 1 shelves, or vintage thrift store finds, reminding us of the centuries-old game of copying, replication, and aesthetic appropriation in the realm of housewares.

As with the canvases, Fuchs’ ceramic pieces include subtle peripheral information: slight local color shifts, even hints of shading from rim, to sides, to interior. A polka-dotted mug has a “chip” in the rim. A red mug, upon inspection, carries a “stain” in the bottom from a beverage it never held. It is a similar strategy to her “paintings of paintings,” aligning the illusion very close in scale and dimensionality to its referent, the closeness being key to the questions it poses.

Over the years, Fuchs has homed in on a central philosophical crux of painting. The questions she asks lie between representation and presentation, and deal with how her own personal archeology is interwoven with larger collective histories. Always aware of the personal and emotional stakes explored through her subject matter, she now seems to be excavating broader phenomenological stakes of our pictorial technologies.

As complicated a semiotic object the facsimile of a simple mug is, it’s hard to say there’s an actual mug anywhere that’s not equally complicated in the same ways, except maybe in our childhood recollections. In Jean Baudrillard’s essay Ecstasy of Communication, he claims that a system of objects is no longer possible. I doubt it actually ever was.

‘Francesca Fuchs: Paintings and Mugs’ at Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas, March 7-April 18, 2020