Francis Bacon, Triptych August 1972, 1972, oil and sand on canvas, Tate. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. / DACS, London / ARS, NY 2019

Francis Bacon: Late Paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gives its viewers an opportunity to delve into the literary and philosophical foundations that support Bacon’s famously atheistic world of blood, meat and bone. Late Paintings, originally conceived by Didier Ottinger, Assistant Director of the Centre Pompidou under the title Bacon: En toutes Lettres, appears at the MFAH with a tighter chronological installation and a new title.

Despite the somewhat shifted focus, Late Paintings retains its connection to Ottinger’s conceit of highlighting the influence of literature and philosophy in Bacon’s painting. Wall texts throughout the exhibition provide literary and philosophical context for Bacon’s pictures. Toward the end of Bacon spelled out, Ottinger’s catalogue essay for the Paris exhibition, he writes, “The inventory of Bacon’s library, carried out by the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Trinity College Dublin, records more than one thousand and three hundred books. If the works of Aeschylus, Nietzsche, Bataille, Leiris, Conrad and Eliot stand out… it is because these authors share certain poetic and stylistic values that resonated with Bacon.”

Ottinger goes on to describe that affinity as a denial of philosophical idealism. Plato famously despised the material world, painting it as a mere shadow of an ideal reality that exists in an entirely different realm. How else to explain the fact that vision and the images it produces for the mind deceive, but that two plus two equals four always stands as an indisputable fact? The incorporeal ideal of mathematical perfection was for Plato a higher reality than flesh and blood.

Even Aristotle, Plato’s younger contemporary, friendlier to the importance of the dusty matter from which we’re all made, traced the chain of actuality and potentiality back to an unmoved mover. If we are not to be trapped in an infinite regress of causality, Aristotle argued, we must find ourselves face-to-face with an ideal form of causation that is not itself caused. Centuries later, Christian and Muslim scholars like Thomas Aquinas and Ibn Sina would employ Plato and Aristotle to provide philosophical support for theological revelation.

“Man now realizes that he is an accident, that he is a completely futile being, that he has to play out the game without reason.”

-Francis Bacon (from the catalogue Francis Bacon: Books and Paintings)

But for Bacon, Aeschylus, Nietzsche, and the post-structuralist philosopher Gilles Deleuze, the idea that an infinite regress of explanation is repulsive to rationality is no reason to deny it. If anything, it’s a reason to deny rationality. Whether in the form of Plato’s overarching ‘Good,’ Aristotle’s ‘Unmoved Mover,’ or the monotheistic God in the traditions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, human rationality is affirmed in the necessity of bringing material explanation to an end in an immaterial reality.

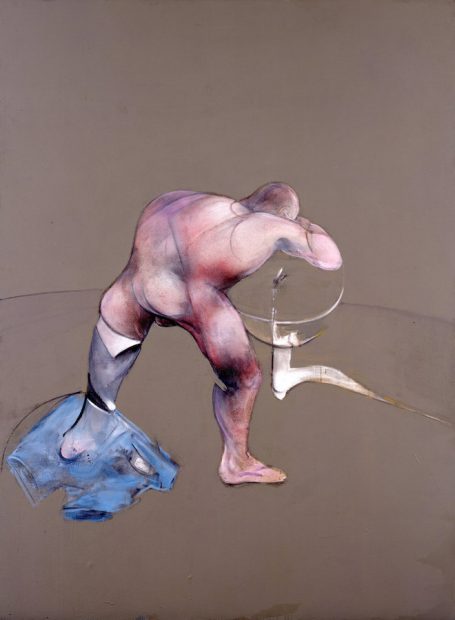

Bacon’s pictures seem to attempt to deny the rational world. Bodies bleed into their environments. In Man at a Washbasin, a naked, fleshy figure merges with the sink over which he hunches, one leg trapped in a pair of shorts that merge into a flap of skin that seems to be peeling away and merging with the cloth. For the atheist, what, after all, distinguishes a man from a washbasin? Take the basin and the man down to the molecular, the atomic, and the quantum scale, give no quarter to the concept of the soul, and there would seem to be no difference at all. The basin and the man, as the pre-Socratic Democritus described reality, are nothing more than randomly swerving “atoms in the void,” so why shouldn’t they collide into each other, becoming one?

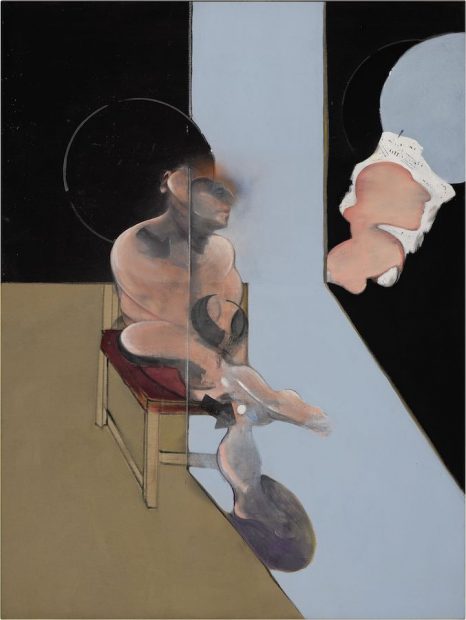

In Triptych, 1970 the coital fusion of the two male figures in the center panel suggests something beyond sexual union. There is little division between the two; fused at the molecular level they become a single hybrid creature, sharing skin, limbs, atoms and identities. They become identical. Even the blue color of the oval wrestling mat on which they grapple seeps into the pink of their skin, suggesting that a man, far from being distinguished by a rational mind as Aquinas would have it, is just one more object in a universe of matter — one more slab of meat in the butcher’s window.

Francis Bacon, Sand Dune, 1983, oil on canvas, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. / DACS, London / ARS, NY 2019

Throughout the exhibition, Bacon’s famously bizarre swingsets and trapeze wires emerge out of improbable geometries and shoot off the edges of the canvases into… where? Nowhere. Everywhere. Perhaps they meet up and connect with other irrational prisons and machines, linking together in an infinite web like Deleuze’s famous rhizome. Just one damn machine after another. In some of his late canvases, Bacon’s slabs of flesh merge almost entirely into their environments. Human flesh becomes sand dunes, jets of water and splatters on the ground. Dust to dust.

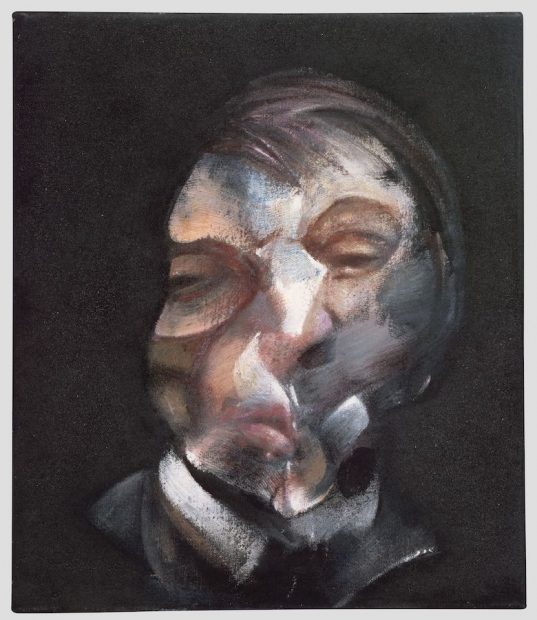

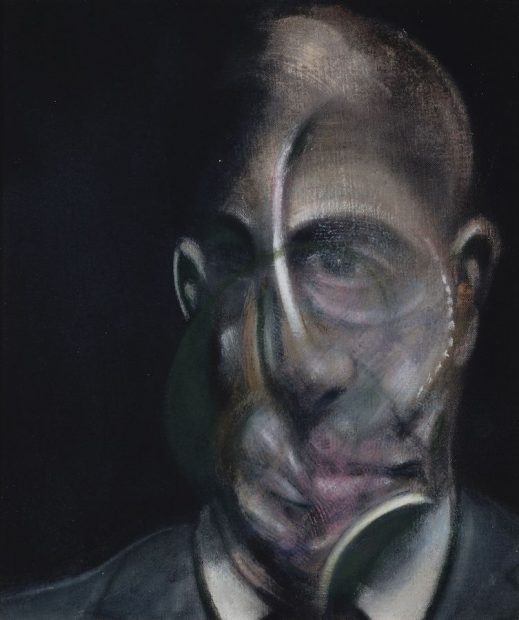

In his 1981 book on Bacon, The Logic of Sensation, Deleuze writes: “Bacon thus pursues a very peculiar project as a portrait painter: to dismantle the face, to rediscover the head, or make it emerge from beneath the face.” Deleuze’s distinction between the head and the face is something that anyone who has ever seen a dead person, a photograph of a decapitated head, or even a fake decapitated head in a film intuitively understands. The head, devoid of life, has no face.

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Michel Leiris, 1976, oil on canvas, Musée national d’art modern-Centre de création industrielle, Paris. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. / DACS, London / ARS, NY 2019

The human face is an animated thing. Animated by blood, nerves and the brain, yes, but also animated by love and hate. Science has something to say about blood and nerves but almost nothing interesting to say about love or hate. Are Bacon’s portraits heads? Not really. The small portraits in Late Paintings, bruised, deconstructed and mutilated as they are, seem all the more alive for it. Dark and rich, full of personality, they are the most conventionally beautiful paintings in the exhibition. Bacon’s portraits are, without question, faces. There is a danger in drawing too clean a parallel between the philosophical and psychological theories of many of the writers highlighted in Late Paintings and Bacon’s paintings themselves.

Francis Bacon, In Memory of George Dyer, 1971, oil and transfer letters on canvas, Foundation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. / DACS, London / ARS, NY 2019

Painters are often oblivious to or in denial of the multiple meanings contained in their work. They are, after all, primarily in the business of making pictures, not crafting coherent theories of reality. If Bacon claimed to be an atheist, it nonetheless seems obvious that the art of the Catholic Church dominates his every painterly gesture. Bacon’s painterly language is not a denial but a subversion of the visual language of the Catholic Counter Reformation. From his often-used triptych format, to the gaudiness of his trademark gold frames, and the intimately scaled and very human portraits of important intellectuals, it becomes clear that Bacon is a profane, heretical, but nevertheless very religious painter.

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait, 1981, oil and dry transfer lettering on canvas, private Collection. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. / DACS, London / ARS, NY 2019

Cast against the modern, urbane anarchism of Duchamp, Bacon is a wild-eyed wilderness prophet. Where Duchamp simply neglects the tradition of religious painting, choosing instead to put junk on pedestals and play chess in a dinner jacket, Bacon seems furiously intent on rescuing painting from oblivion. Bacon is not an a-theist — he’s an anti-theist, and those are very different things.

Scheduled through May 25, 2020, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.