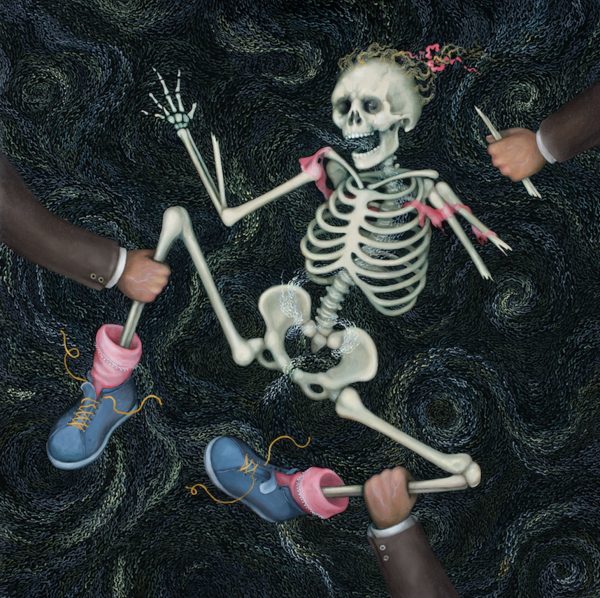

My introduction to Texas artist Julie Speed’s work was a pencil sketch of a female skeleton being held down, legs open, by figures outside of the frame — their identities as perhaps politicians or men in power hinted at by their strong hands and sophisticated sleeves, as a pack of sperm enter her.

The sketch would become a painting titled The Rights of Sperm. Speed shared the work in progress on Instagram around the time the state court of Alabama declared abortion illegal even in cases of rape or incest, in May 2019. The image made me feel both terrified and grateful — terrified by the state court of Alabama’s decision and grateful someone was making art about it. As one follower so precisely put it in the comments: “thanks for putting my shock and rage into words and art.”

“It [the state court decision] came on the radio and my hair went on fire and I started that painting,” Speed says. “Usually if I have a bee in my bonnet and I try and paint it it comes out like shit because it’s too intentional in a, like, ‘I’m going to tell you what I think’ kind of way, but this one I didn’t care — I just went ahead.”

I was reminded of that bracing introduction to Speed’s work when I saw The Rights of Sperm, now completed, hanging on a wall in the sitting room of her Marfa studio, near her computer and a small table with two bottles of tequila and a cluster of shot glasses. Speed’s additions — sperm swirling around the entire canvas and the skeleton made juvenile with pink socks and a hair bow — bring the point home.

Speed, 69, has built a successful career as an artist working with collage, assemblage, painting, mixed media, printmaking and more. Her Renaissance-style exactitude melds seamlessly with contemporary themes to attract a range of dedicated admirers, and has garnered her solo exhibitions at The El Paso Museum of Art, Taubman Museum of Art, Austin’s Flatbed Press, Austin Museum of Art (now The Contemporary Austin), and more. Speed’s figurative works are hard to place in both reality and time. Her menagerie of humans, often donning a third eye or limb, and animals — birds, cats and sharks to name a few — are both humorous and folkloric.

Mostly self-taught, Speed dropped out of Rhode Island School of Design after studying there for a year. On the day of our interview, she wears a flannel shirt and vest paired with her trademark backwards pageboy cap and three long braids. Her silvery voice is juxtaposed by some well-timed cursing.

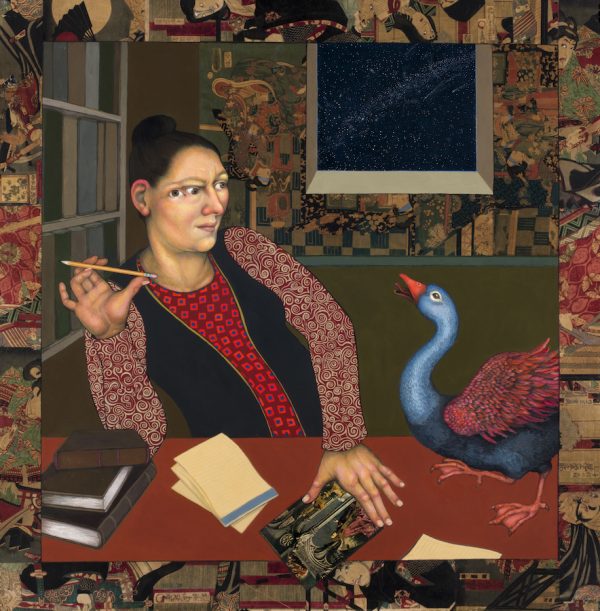

Current events, like the Kavanaugh hearings of 2018, often make their way into Speed’s work via the radio in her studio. Speed says she experienced something similar to Dr. Christine Blasey Ford as a young woman, and the way Dr. Ford’s memory was scrutinized during the trial inspired her to create a painting titled The Arraignment, which hung alongside The Rights of Sperm during our visit.

The Arraignment features one of Speed’s signatures — reclaimed, collaged paper (often Japanese Woodblock paper) — applied to top corners of the painting and the main subject’s clothes. The opposing corners represent male and female domination; one side features male warriors and women tied up and gagged, the other side a gallant female swordfighter on horseback. Kavanaugh lurks in the background, flashing from underneath a court robe, beer in hand.

Speed has been dutifully collecting paper since she was a teenager, and she restricts herself to using damaged paper. The damage is caused by worms, fire, flood, or child’s play, and it forces her to be more imaginative. She used to scour flea markets and go on buying trips around the country for the reclaimed paper. These days, she mostly sources it on eBay.

“My rules are, I’m not allowed to use a computer to blow anything up or down because that would make it an open-ended game and then I’d go nuts, but I’m also not allowed to wreck any good books,” Speed says. “So it has to be books that are already torn apart.”

Speed has operated a lively Instagram account (@speedstudiomarfa) since fall of 2016 via an iPad. She doesn’t have a cell phone. She regularly shares works in-progress, videos, process tips and amusing anecdotes, like how a sailor in one of her paintings, with the name “Wanda Lynette” tattooed on his arm, came from an unlikely source — Speed asking a UPS man his grandmother’s name.

Speed got some traction sharing in-process videos during her East of the Sun and West of the Moon solo show at the El Paso Museum of Art in 2018, and she wanted to continue sharing similar content. The three-channel video and sound installation, Close-Up Room, features music she listens to in her studio, and projects images of in-process works to encourage people to further examine the finished pieces in the gallery.

“There were pictures of me doing it so you get a really clear picture of ‘this is a person with their hands’ because so much stuff now is just done on the computer and then printed out on giant Inkjet printers,” Speed says. “You see the details, then you could walk back into the main body of the show and go, ‘Oh, I didn’t notice that before’.”

“So many museums now build at the scale where every room is this giant abstract painting,” Speed says. “So you get used to standing way back from the painting and it doesn’t occur to people as much to walk up and look at the details.”

For Speed, posting on Instagram is a way to continue the spirit of education through an online presence. The app also acts as a working archive, where she can revisit a piece at an earlier stage. Being self-taught, Speed experienced much trial and error to hone her techniques. She says she never appreciated the attitude that a certain level of artistic knowledge had to be earned by an academic degree.

“There were a lot of older artists and I would ask a technical question and they would be like, ‘Oh, well, that’s proprietary. You know, that’s my secret.’ They were really shitty about that,” Speed says. “So I go out of my way to say, ‘and then you take this and you put it on this and do it like this and here’s a picture’.”

Speed also joins the growing wave of artists who challenge the old gallery system by selling their work directly through social media and acting as their own dealer. The art market is changing quickly, according to Speed; when she first moved to Marfa in 2006 she would rarely sell paintings through the internet. She says the majority of collectors who reach out to her typically already own her work, or are a friend of someone who owns her work. But that’s not always the case.

“I would still sell paintings by JPEG, but only to people who already owned my paintings or at least had seen a show of them someplace,” Speed says. “But now I sell paintings to people who’ve never seen my paintings [in person] ever, anywhere.”

Speed originally quit her New York gallery in order to be more in control of her own sales — she needed to retain more works in order to set up a foundation for her home, studio and artworks. Speed and her husband, drummer Fran Christina, are partnering with the Austin Community Foundation to turn Speed Studios into a foundation when the couple dies.

The ACF serves as an umbrella organization for many non-profit initiatives. It holds the funds that comprise the endowment for the museum. When the time comes, the fund advisors and the ACF will implement and govern the Speed Museum and Archive.

Eugene Sepulveda, one of Speed’s longtime friends and collectors, serves on the foundation’s board and has agreed to leave his personal collection to the foundation.

“The goal is to open the studios and home as public spaces exhibiting Julie Speed’s work and to establish a big enough endowment that operation of the museum is covered in perpetuity, and to provide residencies for songwriters, poets and printmakers,” Sepulveda says. “We’re quite far along in raising the endowment.”

Speed says while the couple has certain ideals for how the place will run when they’re gone, they’re keeping stipulations open to future interpretation.

“If there was an earthquake out here and for some reason Marfa was no longer an art tourist destination in 20 years, which is possible, then we croak and the board could decide, ‘Oh, well just sell the property and take the endowment and endow the paintings to some other place’,” Speed says. “I don’t want to make a bunch of rules ‘cause they might not be practical in like 90 years or so, when I die,” she adds, laughing.

Speed’s goal is to leave 200 paintings to the foundation. When she pinpointed this number she was in her early 60s and only had 50 paintings available. She did the math — she can do seven oil paintings a year — and realized she had to get to work and commit to longevity. “I called the gallery the next morning, but quitting smoking took a little while.”

Speed regularly hosts open-studios, and invites locals and travelers alike to enter her workspace which doubles as a gallery. Her proximity to the Chinati and Judd Foundations (she’s only yards away) make the eventual Speed foundation well-positioned to attract art-minded visitors.

“It’s not like anybody’s going to drive all the way to see a Julie Speed painting, but if you can do a two-fer…” Speed says. “And you gotta have some women somewhere.”

Sepulveda says because Speed is a woman artist, there’s a risk her work won’t get the recognition it deserves. By leaving both his Speed collection and a significant pledge to the endowment fund, Sepulveda hopes the foundation will help secure Speed’s position as an significant contemporary artist.

“Donald Judd established Marfa as an epicenter of the modern art world; Julie Speed is one of the leading artists ensuring Marfa is a thriving, relevant place for contemporary artists,” Sepulveda says. “There will be a Me Too-ish moment in the art world, but until then, we’re intent on preserving the work of important contemporary artist, Julie Speed.”

Out In Marfa

Speed and her husband moved from Austin to Marfa in 2006 and acquired the studio (the building is circa 1916) and land to build their house on. Their home, built with aerated concrete block, was completed three years later, in 2009. Their land hugs the Chinati Foundation grounds, with clear views of Donald Judd’s 15 Untitled Works in Concrete.

Attached to the studio is a printmaking room, with an etching printing press, complete with two 300-pound rollers. The press had to live outside under a tarp while the building was being renovated, but when it was time to move it back inside, it didn’t fit through the reconstructed door. Speed’s husband took the press apart and put it back together.

“That could be like some special circle of hell, right? Like really heavy IKEA furniture,” Speed laughs.

The studio was the former jail for Fort D.A. Russell (which is now the Chinati Foundation); then it served as the Texas Land Bank offices. People who used to work in the building claimed they had some encounters with a friendly ghost named Johnathan, who Speed has yet to meet 15 years later.

“We asked, ‘So is there anything about the building we should know?’ We were thinking like plumbing or electricity, and they said ‘Well, there’s Jonathan…’ and then they went on about Jonathan the ghost who would move things around and make noise, but you didn’t have to worry about it,” Speed laughs.

Most days after she is done toiling away in the studio, she spends time stacking rocks, doing outdoor projects and gardening. She says getting her hands in the soil is therapeutic. Volcanic rocks, which are featured on a rock wall around her home, are collected from a friend’s ranch in the Van Horn Mountains. Speed says stacking rocks is good practice for her because it’s “like doing collage, only 3D.”

For Speed, an affinity for the desert landscape and accompanying quiet of West Texas began when she was living and working in Austin. On road trips out West on I10, as trees give way to shrubs and the Edwards Plateau kicks up near Junction, Speed says this shift in geographies caused her to take a sigh of relief and whatever relationship woes or self-pitying thoughts she was having would start to retreat.

“Every time I get to that shoot [in Junction] I feel like everything was so big that I would get really little, so whatever it was that was bothering me would also get little and then it would just blow away,” she says.

Before she moved to Marfa, Cabin 10 at Marathon Motel & RV Park (which used to go for $24.99 a night) helped her find some respite and perspective.

“I’d just sit in the chair and look at Santiago Peak and drink tequila until I’d fall down, then I’d wake up the next morning like ‘all better’ and that was my mental health trip to West Texas,” Speed says.

The day-to-day routine in Austin wore her down, she says. Going to get the mail from her studio required getting in the car and encountering a symphony of city noises — honking, helicopters, leaf blowers, train horns — and by the time she’d settle back down in the studio she’d be totally disconnected from the work.

Speed says, “Here I can put down my brush and walk to town, get the mail, walk back, and the whole time… ”

“…I saw one person maybe,” I add, laughing.

“And they’re nice to me!” Speed laughs. “So when I walk back in the studio, I can pick up and be exactly where I left off. Which doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it makes all the difference in the world because there’s not all that stopping and starting time.”

When asked how it feels to her to be a Texas artist, Speed describes it being the first place she’s really settled down. And being able to see the horizon puts her at ease.

“When I got here I was like, ‘Oh, I can relax. No one can sneak up on me.’ So that’s what it feels like,” Speed says.

On Her art

At this stage in her career, Speed has given many interviews and been the subject of catalogs, namely two UT Press monographs, Speed Art and Julie Speed: Paintings, Constructions, and Works on Paper. She’s often described as an iconoclast whose work is “absurdist,” “enigmatic,” or “surreal.” She’s pretty used to hearing what people think about her art, and she’s good at trying to explain it. I think she sums it up perfectly in this video interview with Texas Monthly where she talks about her incorporation of popes as an excuse to use Cadmium red paint. For Speed, it’s all about the composition.

“I put together all the pieces in a way that makes me happy compositionally, and make sense psychologically,” she says.

She uses the example of overhearing a museum docent describe a pomegranate as symbolic in the context of a work of art, but thinking to herself, No, they just wanted to balance out the composition. She’s not unconscious of symbols. She’s just not heavily motivated by them, which is surprising given her seemingly intentional literary scenes. Speed discusses the role of symbols as having multiple, or no, meanings. For example, a fish: it may be a Judeo-Christian reference, a magic fish that grants three wishes, or just a fish. The focus is on colors and spacial balance that create a mathematical harmony.

“If we didn’t have a category called ‘art,’ you’d still be there moving your chair and arranging shit on your plate,” Speed says. “And when you sat down on the ground, you’d be arranging stones and stuff. You just do it in the same way that if you’re humming a tune, right? The distance between the notes and how heavy one is and how light another note is. It’s like there is a right in a wrong arrangement, and that to me is what makes a song or a poem or a story, or a painting or a good soup. If you put the right amount of vegetables of the right colors in the pot you get something that tastes good.”

“It’s also just accidental. I don’t know — you drive by a hay field and you look at the hay bales and the light is hitting them a certain way, and you get this strong feeling like: I’m here now, pay attention.”

A wall in Speed’s studio near her easel displays taped-up images of a skull, elephant feet, and more, and also holds a box collage called Three Black Balls from her 2017 series Military Evolutions. She meditates on shapes and balance, sometimes flipping things upside down or photographing her work and uploading it to the computer to change it into black and white. In their early stages, Speed refers to the people in her paintings as “blobs.”

“The people — I don’t know what they’re going to be, but I just keep painting, and then one day they’ll look back at me. And then I go, okay, they’re there,” Speed says. “Then the trick is, because the painting will last another month or something, I gotta not screw them up.”

Speed grew up identifying with the male or genderless characters in books, which comes across in her art where women are portrayed strongly. She says she has no interest in painting people who wear their gender first. The appearance of popes and sailors in Speed’s work can partially be attributed to the timeless qualities of their clothing.

“I don’t usually paint women so their sexual characteristics are their leading characteristics, and the same thing with their clothes. Usually I try to take it out of time.”

As months pass and layers of paint amass, so do the characters or scenes in the work. Speed draws inspiration from day-to-day and current events, and daydreams in the bathtub.

“These paintings — because they’re representational — everybody always thinks I must get an idea, then draw a painting of it, but it’s the opposite. I make a composition,” Speed says. “So the implied narrative [gets] built by the composition, and current events, and shit that happened to me when I was three, and a fairytale I read.”

She adds: “If I try to be the boss of it and to be very specific or didactic or ‘I’m really smart and I’m going to teach you a lesson’ — right? — then you’re just another asshole with a propaganda poster.”

Speed typically works on a couple of paintings at once, to allow the oil paints to fully dry before the next layer, and to let collage pieces be weighed down and flattened overnight. To keep herself creatively limber, she uses her entire arsenal: oil paints, collage, gouache, printmaking and 3D boxes.

“I was painting popes for a while and then people started asking for popes and I had to stop painting popes. Because it was like, ‘Oh, this is a trap,’ — and that’s why I never take commissions,” Speed says. “As long as I keep changing it up, then I’ll learn something in one form, then I can apply it to the next form and it keeps me from getting stuck.”

On Inheriting the “Pay-Attention-To-Detail” Gene

Speed’s tendency toward meticulousness and habit of working small seems to run in her blood. You see it in her visor affixed with magnifying lenses, which she wears inches from her face and keeps close to the canvas.

Speed’s mother started throwing pots at age 65, after retiring from a secretarial career. A finely crafted teapot by Speed’s mother sits in a kitchen cabinet at Speed’s — it sports bunches of tinier teapots on its lid. It sits near a hand-crafted metal model of the Russian battleship Potemkin, made by Speed’s father.

“… I’m saying why I can’t do big abstract paintings even though I really like them,” Speed says. “It’s like, I don’t know — how could there be a gene for, like: pay-attention-to-detail… ?”

Speed was encouraged to make her own clothes growing up. “My family didn’t do art, but everybody worked with their hands all the time. When I was a little kid: ‘Here, honey. Here’s a torch and a chisel and a hammer.’ Nobody ever said: ‘Well, you’re too short, you’re only five,’ you know, ‘Here, don’t set the house on fire, bye’.”

That DIY-spirit and ability to find pleasure in one’s projects stuck with Speed, who has been immensely prolific in her artistic career. One of her collectors commissioned Speed’s father to make a model ship — something he never imagined getting paid for. Speed says even though he was in bad health during the project, he worked on it right up until he died.

“He was sick and in pain but he said ‘It’s the work that saves you.’ He could go in there and get into the flow and then the pain would go away, and the fear of death and all that would go away — from all the time that he could be with his hood on, going like this.”

Current + Upcoming Works

Speed’s Purgatory of Nuns series will be on view at Bale Creek Allen Gallery in Austin starting March 6, opening from 7 to 10 p.m., and it closes on April 12. In the work, salvaged engravings from an 18th-century European guide to Catholic sects are altered with gouache and collage; the works are illustrated like a birding guide. Speed says she’s looking forward to filling up the small gallery with the 42 works, which will be on view to Springdale General pedestrians even when the gallery is closed via the large front window.

Cattywampus Press produced a limited edition box set reproduction of the series, and is working on a more accessible hymnal version, designed by Lindsay Starr, which should be available by March 6.

At the time of publication, Speed was on a “dark skies binge,” repetitively painting small white dots on different shades of black. The night sky started creeping into Speed’s paintings five or six years ago, which led her to coin her Dark Skies series.

“I love going outside, looking up and seeing that Milky Way cloud of my home galaxy, stretched out there above, reminding me every night just exactly where I am in the universe, and how small I am,” Speed says. “That perspective makes me happy.”

Speed’s ‘Purgatory of Nuns’ series will be on view at Bale Creek Allen Gallery in Austin starting March 6, opening from 7 to 10 p.m. It closes on April 12.