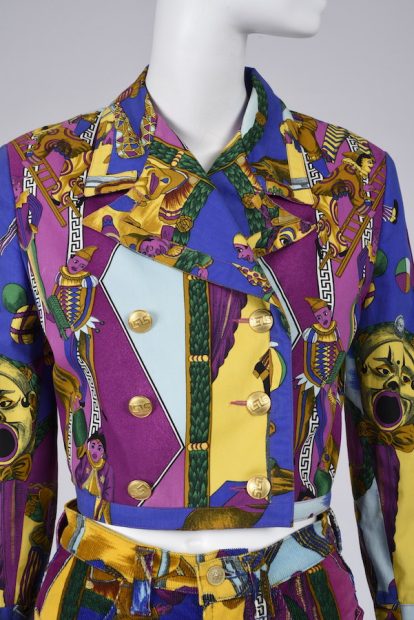

Gianni Versace, Dress, 1994. Rayon, acetate, silk, metal and rhinestones. Collection Phoenix Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Kelly Ellman, 2008.288. Photo by Ken Howie.

What did your 1990s look and feel like? Björk, or Wu-Tang Clan, or both? Riot grrrl’s Doc Martens, or Versace’s gold safety pins? The 1990s is one of the few recent decades that managed to maintain a loose consistency, especially throughout President Clinton’s two terms. It was the last full decade before the digital era hit hard, and things seemed to shift at a more relaxed pace. We kicked off 1993 with Blur’s Modern Life is Rubbish, and ended 1999 with Blur’s Think Tank. Spike Lee released Mo’ Bettter Blues in 1990, and Summer of Sam in 1999.

In the 1990s, the U.S. was mostly war-free (Operation Desert Shield ended in early ’91; the Cold War ended in 1989 with the fall of the Berlin Wall), and mostly financially sound. The cataclysmic events in this country in the 1990s were Kurt Cobain’s suicide in ’94, and the Oklahoma City bombing in ’95. O.J. went on trial and got off. Clinton was impeached (and also got off). That’s about it.

I graduated from college in 1992. For me, the ‘90s was the decade where Gen X-ers attempted, and failed, and then finally succeeded at becoming something like grownups. We didn’t have money, but we had great music, and some solid art and literature (the UK and Europe helped out in that regard), and “style” was something anyone with any aesthetic sense could achieve via a trip to the thrift store and a little imagination.

Maybe it was my age or generational disposition, but to me the 1990s weren’t, culturally, a very bullying time, and the big exhibition at the McNay in San Antonio, called Fashion Nirvana: Runway to Everyday, reflects that. Which also means that it feels low stakes. It’s a pleasant walk-through, but hardly bracing, or even thought-provoking. Maybe it’s the preponderance of Oscar de la Renta gowns on show, or the strange absence of anything from Marc Jacobs’ controversial (at the time) Perry Ellis “grunge” line of 1993. The clothes here, which are the main event of this show, are fine. Most of them come from the very respectable Texas Fashion Collection of the University of North Texas. I do love me some vintage Todd Oldham.

Todd Oldham, Cocktail dress and skirt, 1996. Silk ribbon. Texas Fashion Collection, University of North Texas, Gift of Todd Oldham Studios

But it’s the things swirling around the fringes of the clothes — the art and music videos meant to give this “fashion nirvana” a bit of context — that are the best thing about the exhibition. I spent a lot more time with the large projected videos by Rineke Dijkstra, Pipilotti Rist and Mariko Mori than I did with the clothes. Maybe I’m exactly the wrong age for this fashion show. I remember all these fashion designers so clearly — Armani, Tom Ford, Dolce & Gabbana — and many of these designers and labels are still blowin’ and goin’. Yves Saint Laurent. Escada. The names hardly induce pangs of nostalgia.

To be fair, the low-key, non-bullying nature of the decade allowed for something like fashion democracy to set in, and you can see that here. Back in the ’90s, I don’t remember feeling any pressure to spend money on clothes. If anything, the over-the-top extravagance of some designer duds suffered nearly instantaneous devaluation via comedy: Absolutely Fabulous’ Edina (“It’s Lacroix!”) saw to that. It was also the first decade that street style and various counter cultures more visibly infiltrated and deflated WASP ideals of high fashion. A Carolina Herrera dress was pretty, but was it exciting? How could it be when hip-hop was continuing its steep ascent, and indie rock (then called college radio) was a valid, if not assertively anti-fashion, style.

Even in my late 20s — and maybe this was because I was a journalist and not a socialite — I didn’t know a single person who cared if they ever owned an Alaïa, or even an Alaïa knock-off. We were happy to just look at the occasional Ellen Von Unwerth photo of Naomi and Christy and Kate wearing Alaïa. Shrill aspiration hadn’t yet become pandemic. Perhaps chalk that up to not having anything remotely like Instagram; back then, many markers of “status” were getting harder to define. In response to the Boomers’ embrace of Reaganomics — their rejection of their own late-’60s ideals — Generation X was, in fact, allergic to conspicuous consumption. Our favorite movies were Slacker and Clerks and Bottle Rocket. One of the villainous markers of the Heathers in Heathers was their expensive wardrobes. High fashion didn’t seem to hold much dictatorial sway on anyone under 40.

In 2016, I wrote a review titled “Too Soon?” on a survey show of 1990s art at the Blanton in Austin called Come as You Are. One of the points I made in that review still stands in relation to the McNay’s current show. It’s this: the social and political concerns that rose to the top in the 1990s are the very ones we’re dealing with today. Climate change, identity politics, feminism, globalism… . These things feel more urgent now, because of mounting backlashes and because they actually are. But they felt urgent to us then, too.

Isaac Mizrahi, Desert Storm, 1991. Silk georgette. Collection of Isaac Mizrahi. Image Credit: Jason Frank Rothenberg.

In other words, either in spite of the digital age or because of it, the pitfalls and roadblocks of humanity have not moved on very much in the last 20-some-odd years. Fashion, in its role as a response to a political moment, has gotten a little stuck. In comparison, think about how vastly different the late 1960s were from the late 1940s. Or the late 1970s from the late 1950s. Back then, 20 years meant jarring and unexpected and thrilling leaps in moral codes, political norms, social expectations… and therefore, clothing. But what major social gains have we made since 1999? Our attention spans are shorter, and our tastes ever-more-cyclical and backward-looking; we’ve stunted ourselves. Instead of making massive and collective leaps of progressive wisdom, we buy hand-held personal computers that we call phones, and stare at them. We spin Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders as new news, but these men, and men like them, were alive and well and shaping opposing poles of pop and political culture 20-plus years ago.

In light of this and the McNay show, I’d add something sort of strange, but also somewhat reassuring about time slowing down as it speeds up. The kind of democratized mash-up of “anything goes” fashion that took hold in the 1990s still applies for anyone who wishes to apply it. There is no coherence or consensus on fashion runways anymore. There are trends, sure. But they last three minutes, and no one aesthetic line of thinking shakes out as supreme. Most of the clothes on view at the McNay look good. They also look a lot like what clothes look like now. If the thrift stores these days weren’t so damn cleaned out by aggressive online re-sellers, we all really could skip the annual trip to Neimans, and forget that Kylie Jenner and her lilac Versace gown even exists.

‘Fashion Nirvana: Runway to Everyday’ is on view at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio through May 17.

2 comments

A reference to the wonderful Jennifer Saunders, darling, a quick slide and shuffle to Deee-Lite on the hardwoods, gallons of strong coffee and my Sunday morning was complete.

Great article, I love the angles you are pulling. As a late Boomer the ‘80’s were my transition from college to the real world. Some of us didn’t trade in our DM’s for shoulder pads and Reaganomics, or as I lived in London at the time, it’s Uk variant that was Thatcherism.

The issues of the day are urgent now and were urgent then and yes, yes yes we have stagnated. Smart phones drive us into “enlightened” individualism and as we retreat into our own heads (or maybe another part of our anatomy) we seem have lost the concept of the collective.

Again great article, fashion as the allegory. It made me think of Vivian Westwood, safety pins, bondage shirts, technicolor mohawks and the Kings Road, Chelsea.

As the 90s began, I was living in Seattle, which made my fashion choices very easy. Not that I cared. A friend of mine describes me as the guy going to art openings in a turtleneck. I had my flannel shirts, sure, but mostly because it was cold and wet, not because it was cool.