Harriet Actress Cynthia Erivo.

Maybe it was Cynthia Erivo’s refusal to perform at the BAFTA Awards (the British equivalent of the Oscars) this year, because no black actors or films were nominated. Or perhaps it was recalling conversations with my buddy Ollie when I was a valet at Fort Worth’s Worthington Hotel back in the day. Whichever it is, recently I am left to ponder this: Should black artists say “yes” to participating in exhibitions, talks, and workshops focused on blackness during Black History Month? It’s good work if you can get it, to be sure. But calling on black artists for art jobs and exhibitions only in February is exploitative, and it should stop.

Beyond the tokenism inherent in these gestures, they do little to encourage real inclusiveness. We need look only to #OscarSoWhite, #GrammysSoMale, and glaring omissions in other industries to see that tokenism isn’t cutting it in 2020. At best, it puts a white band-aid (because it’s hard to find black band-aids, or dark-colored ballet shoes, as long as we’re on this topic) on the lack of diversity in art.

I, too, have been guilty of contacting black artists for February exhibitions and talks. When I ran the art gallery at Tarrant County College, I would reach out to black artists for any number of Black-History-Month-themed programs. But if I can offer a small defense — my exception to this rule (more on this in a moment) — I also called on black artists for programming the other 11 months of the year.

Back when I was a valet, in the heyday of the pre-Hollywood-movie-lot that Sundance Square in Fort Worth has become, the venues Caravan of Dreams and The Black Dog Tavern still hosted live jazz every week; the Coffee Haus was still thriving, pre-Starbucks invasion, and there were still people milling around that didn’t fit into comfortable categories. In the lull between picking up and dropping off cars, the other valets and I would get into long conversations about everything.

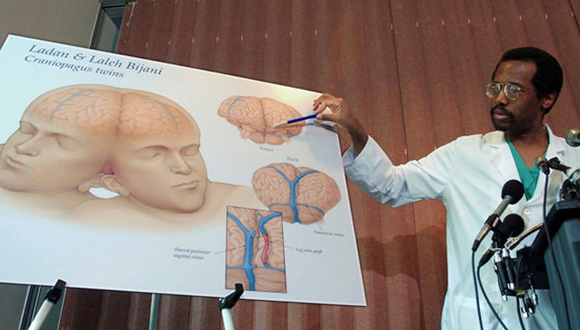

In one conversation, Ollie and I talked about whether or not Black Excellence (we didn’t call it that back then) should be a conversation about the general ongoing merit of black artists, versus the flash cards of one-time exceptional achievements. I argued for the former, believing that if we put too fine a point on Ben Carson’s pioneering brain surgery props, for example, he would be seen as an exception rather than a man capable of greatness simply because he is great, not because he is a “great black man.”

Ben Carson.

Ollie’s argument was that if we don’t know our heroes, often through special promotional pushes, generations could lose out due to glaring omissions from history books. He had a point. Although learning more about 2015-2020 Ben Carson was a net loss for me. I wouldn’t put him on my list of role models.

I think we can agree that it’s possible to recognize the accomplishments of black folks and work with black artists year-round, instead of making February the month to push the hardest for black recognition. I won’t throw out the baby with the bathwater, but I think there are other ways to honor our achievements and to work with black artists.

I bring up celebrating Black Excellence in February and hiring or exhibiting black artists in the same argument because they speak to one issue: doing little while claiming progress. As Gil Scott-Heron puts it in his 1976 Bicentennial Blues, it is “partial deification of partial accomplishments, over partial periods of time.”

Gil-Scott Heron

This is not to say that black artists should never work in February, but rather that we are now in a new decade and we should begin to look at better ways of including black artists in our ongoing conversations about art, rather than using February to check a box on an institution’s diversity calendar. Any art organization or institution truly committed to recognizing the contributions of black artists, and the importance of equality and representation in art, should dig deep and commit to actively working with black artists throughout the year.

I’ve seen some really great not-in-February shows across the country in the past few years that stand as examples. I’m thinking of the the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (including its FOCUS exhibitions): it bookended Nina Chanel Abney (January) and Njideka Akunyili Crosby (December) for its 2018 schedule, brought in Lorna Simpson and Stanley Whitney in 2017, and hosted a major Kehinde Wiley retrospective in September of 2015.

FOCUS: Nina Chanel Abney, at the Modern Art Museum, 2018.

Across from the Modern in Fort Worth, the Amon Carter Museum of American art’s Gordon Parks show was also in September (last year). I saw Glen Ligon’s Blue Black, an exhibition he curated, at the Pulitzer Art Foundation in 2017 in August, and We Wanted a Revolution at the Brooklyn Museum in April of the same year. And here in Houston, The Soul of A Nation, Art in the Age of Black Power, which I happened to catch at The Broad in LA last summer, comes to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in April. But if you believe that this is the rule, rather than the exception, you need only do an internet search for Black History Month Exhibitions to see how pervasive black-centered February exhibitions are. My own survey of black artist friends leaves me confident that I’m not the only one who thinks we can do better.

I think black-artist-only shows are great, but could we also get included in group exhibitions (not curated from a museum’s permanent collection) that recognize important contributions to, say, Abstract Expressionism?

We all benefit when we grow our institutions and experiences by making inclusion more of a ten-year plan than a 28-day one (29 this year). We are happy to work in February, as long as you work with us February to February. Museums and galleries could make the argument that their exhibitions are based on the availability of the works for a show, the prerogative of the curator, and exhibition schedules. But I think it’s possible to plan far enough ahead to avoid these conflicts so that we don’t have these conversations in 2025 and beyond.

Artists are the fuel of the art world, and underrepresented artists — black, brown, queer, and female — are burning out. We want to keep doing the thing we love, and to pay our bills with the opportunities we get to work for you. We are Jerry Maguire. Help us help you.

3 comments

Well said Christopher! I couldn’t agree more. And since March is Women’s History month–let’s apply the same to gender-based shows. No more tokenism; yes to inclusiveness for GREAT art.

I work for a corporation that is lucky enough to have a specialized team that only manages the art collection and exhibitions/engagement items surrounding art. There has been a long-standing initiative in the company around diversity months, Black History Month, Women’s History Month, Hispanic Heritage Month, Asian & Pacific Islander Month, et al. The company also fosters business resource groups that are related to similar groups within the employee population. As a result, our exhibitions and activities tie into this initiative and often we partner with the associated business resource group. Outside of a few employee artist exhibitions, this is our sole programming strategy. How do you resolve this with your call for non-participation? In an effort to be transparent: I’m a middle-aged, educated, politically center-leaning conservative, white man. I am also one of the small team who has the joy of helping to manage all aspects of this corporate art collection.

Here is my point, Jared (from the article):

This is not to say that black artists should never work in February, but rather that we are now in a new decade and we should begin to look at better ways of including black artists in our ongoing conversations about art, rather than using February to check a box on an institution’s diversity calendar. Any art organization or institution truly committed to recognizing the contributions of black artists, and the importance of equality and representation in art, should dig deep and commit to actively working with black artists throughout the year.