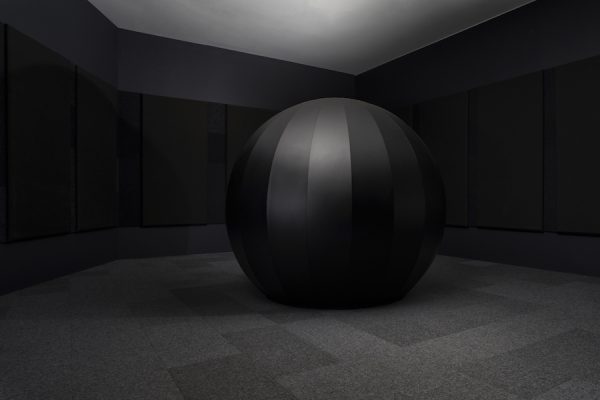

Installation view of Speechless: Different by Design, at the Dallas Museum of Art. All photography: John Smith

Speechless: Different by Design, currently on view at the Dallas Museum of Art, brings together the specially commissioned work of seven artists and designers to create a novel aesthetic experience, challenging visitors to rethink their senses. By foregrounding interactivity and drawing attention to sense perceptions in general, Speechless also considers novel prospects for accessibility and inclusion. A beautifully organized and powerful exhibition, Speechless shines by teasing out of the sensory assumptions visitors bring with them and encouraging new, multisensory and inclusive forms of engagement with art. In particular, the work Sounds of the Earth Chapter 2, by Yuri Suzuki, offers not only a novel experience, but an incisive look at visitor’s expectations.

Sounds of the Earth Chapter 02 consists of a large, matte black segmented sphere enclosed in a dark room. Dispensing with the more typical paragraph or so of museum copy, each piece in Speechless is accompanied by a series of glyphs instructing visitors how to “experience” the piece. In the case of Sounds of the Earth Chapter 02, the glyphs illustrate how to gently place an ear against each segment. The series of sounds surprises the visitor. The sounds, crowdsourced through the DMA’s website, include the ambient sounds of a mall, rushing water, overheard conversations, and outdoor soundscapes. After making a round of Sounds of the Earth Chapter 02, the sounds from within the black segments become more audible after the visitor turns away, no longer disappearing into the ambient soundscape of the exhibition. The integral auditory component of the piece doesn’t stand out until the visitor has been primed to experience it as such. The Sounds installation would be impressive for its size and brooding visual density even without the auditory experience, but the din of everyday life one hears from each section add an entirely new, gentle dimension to an otherwise quite stark presence. Why, the piece seems to ask, couldn’t you hear me before?

Museum goers have likely encountered multi-media or interactive pieces before, but Sounds of the Earth disrupts expectations by emphasizing the auditory and tactile experience over the usually privileged visual. Listen, it says, and to listen, you must break the cardinal rule of typical museum experiences: Don’t Touch!

When I visited Speechless during the winter school holidays, there were quite a few families with young children in attendance. The appeal to children of an interactive art exhibition is clear: with only one exception — Matt Checkowski’s Glyph — the works in Speechless invite touch and physical movement. Misha Kahn’s (T3)* (8)* (J~) * ([..”) * (7^) * (4=) * (F]) * (llii.) * (A) * (!s) * (11) * (‘.v:’)* goes even further than simple touch or gentle manipulation. This elaborate and extensive piece not only allows, but encourages visitors to jump into and onto a forest of slowly inflating and deflating organic shapes that fill a large room in the space. This piece, was, unsurprisingly, a huge hit with the younger visitors. Where else do they encourage you to run and jump on stuff — on art! — in a museum? Khan’s towering but friendly organic shapes bring to mind a Wonderland mushroom forest, while also raising questions about what, exactly, this thing is. Even the title of the piece, which, at least as far as I can tell, offers no hints as to the piece’s nature, raises questions for the perceptual assumptions visitors bring. Is the name intended to be machine-readable? High-level calculus? Maybe an elaborate cypher? Or is this, perhaps, what text looks like to a visitor with severe dyslexia?

By calling into question the assumption that works of art are not to be touched (or jumped on), Speechless questions the implicit set of rules that visitors bring with them about museum visits, and also about how they experience the world more broadly. Speechless demonstrates that our sensory experiences and their meanings are not inborn, but rather developed as a part of broader socialization, amenable to purposeful experimentation, modulation, and change. We can be taught to understand the world in new ways, starting with how we understand art. Ini Archibong’s Theoracle, a glowing Delphic temple of oblong pedestals and ethereal sound, demonstrates this directly. Visitors manipulate the oval pedestals to change the sounds playing in the room that houses the piece, which causes a shallow pool of water at its entrance to ripple in different patterns. Part of the experience is visual: Theoracle sits on a kind of altar in a stark white room to arresting effect, but the piece’s appearance is just one part of the experience. Sound and touch meld themselves with the visual in in this work, which leads visitors to wonder just how it was that sight, hearing, and sound got to be separated in the first place.

Growing public awareness of atypical sensory modalities, dyslexia, and other disorders of expression or sensory reception allow Speechless to raise important questions about the experience of art, and of the senses more generally. Indeed, as Dan Singer writes in the Dallas Morning News, Speechless was inspired by the experiences of Sarah Schleuning, the Margot B. Perot Senior Curator of Decorative Arts and Design at the DMA, whose son has an expressive language disorder. Touch and sound allow exhibition visitors with visual or hearing impairments to interact with the pieces in the exhibition in terms that don’t privilege the visual, and the instructional glyphs insure that those too young yet to read, or for whom reading presents substantial challenges, or visitors that do not read English, are included in the interaction.

The experience of Speechless is highly stimulating, bordering on the overwhelming. At the back of the exhibition space lies an integral but likely overlooked room. Stocked with noise-cancelling headsets, rocking chairs, and weighted lap-blankets, Speechless’s decompression room gives visitors a chance to decompress after their sensory workout. The weighted blankets and noise-blocking headphones help to reassert the visitor’s bodily and perceptual outline, reminding our feeling, perceiving bodies of what is “inside” versus “outside,” and giving our disoriented senses time to reset themselves — hopefully to a configuration slightly more open that before. The decompression room offers a calming counterpoint to the powerful and beautiful yet demanding experience of the works in the exhibition.

In a world of constant, frenetic activity and seemingly endless demands for time, attention, and mental bandwidth, it would be easy to burrow under a weighted blanket in an attempt to escape sensory overload. Speechless, with its welcoming, engaging, and frankly really fun interactivity, demonstrates that such a course would be a mistake. Experiments in perceptual awareness like Speechless offer a way of taking sense perception directly into account, and asks how those with atypical modes of sensory engagement, both with artistic experiences and with the world in general, might no longer be marginalized or excluded. Stretching one’s perceptual assumptions can be challenging and exhausting, but Speechless ably demonstrates that the exertion is worth the effort.

Through March 22, 2020 at the Dallas Museum of Art

Mathieu Debic is the recipient of the 2019 Glasstire Art Writing Prize.

![Misha Kahn, (T3)* (8)* (J~) * ([..”) * (7^) * (4=) * (F]) * (llii.) * (A) * (!s) * (11) * (‘.v:’)*](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/speechless_DMA_Misha-Kahn_4.-Photo-by-John-Smith-600x400.jpg?x88956)