View of Arte Sin Fronteras: Prints from the Self Help Graphics Studio at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, October 27, 2019 – January 12, 2020

Gloria Anzaldúa’s book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, describes the border as an open wound, “where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before a scab forms it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of two worlds merging to form a third country — a border culture.” Borderlands/La Frontera takes on the contradictions inherent in the identities of Chicanx people living in the valley and the realities of los atravesados, the people who live their lives on the border and crossing the border. Similarly, several of the works within the Blanton Museum of Art’s exhibition, Arte Sin Fronteras: Prints from the Self Help Graphics Studio (in Austin through January), speak to the contradictions — cultural, geopolitical, historical — of living on the border between the United States and Mexico.

View of Arte Sin Fronteras: Prints from the Self Help Graphics Studio at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, October 27, 2019 – January 12, 2020

Self Help Graphics (and its Experimental Atelier Program) is a long-running printmaking and print edition studio founded in East Los Angeles. The works in the Blanton show are prints that were produced there, and more directly come from Austin’s Galería Sin Fronteras, founded by Dr. Gilberto Cárdenas to “disseminate the output of the Experimental Atelier Program [and support] the work of Latinx and Chicanx artists.” A couple of years ago, Dr. Cárdenas donated more than 350 Experimental Atelier Program prints — which span decades of printmaking — to the Blanton.

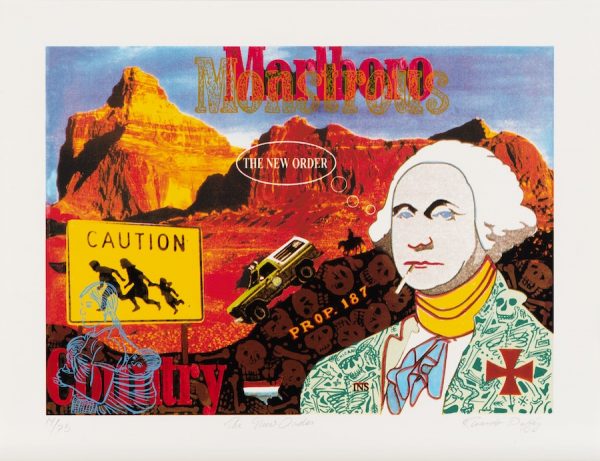

Ricardo Duffy, The New Order, circa 1996–97, screenprint, 20 x 26 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Gilberto Cárdenas, 2017

Ricardo Duffy’s print, The New Order [El Nuevo Orden] offers a criticism of the 1994 passing of California’s Proposition 187, which would have denied public services to undocumented people. In The New Order [El Nuevo Orden], a woman carrying her children makes her way along California’s Interstate 5, which runs between Los Angeles and Tijuana. The family are passing a street sign cautioning drivers to be wary of families crossing the border. The highway is ridden with the dismembered skeletons of people who have attempted to cross the border and an Immigration and Customs Enforcement vehicle patrols nearby. In the foreground, George Washington smokes a cigarette and wears an Immigration and Naturalization Services uniform patterned with the skeletons of Chicanos. The background of the print features the Malboro Man and logo, referencing the tobacco lobby’s effort to defeat Proposition 188 that year, and moreover referencing American capitalist greed.

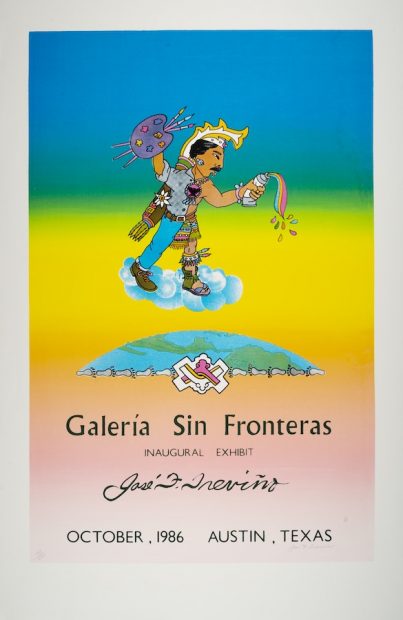

José Francisco Treviño, Untitled, 1986, screenprint, 40 1/16 x 26 5/16 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Gilberto Cárdenas, 2017

Many of the prints directly speak to Anzaldúa’s concept of mestizaje, mixed identities that transcend contradiction, addressed in her book. In the Blanton show, in an untitled work by José Francisco Treviño, the subject of the print is literally halved — one side of his body is dressed as an Aztec warrior, the other side wears blue jeans and a shirt with the sleeves cuffed. The half-warrior’s weapons are a painter’s palette and a tube of paint, and on his chest he bears an Aztec eagle symbolizing the United Farm Workers’ flag. In Treviño’s print, not only does the artist assert his complex identity — Chicano of indigenous descent, worker, artist — but this depiction speaks to the broader aspirations of Self-Help Graphics and the Galeria Sin Fronteras, of rooting themselves at the intersection of art and social justice.

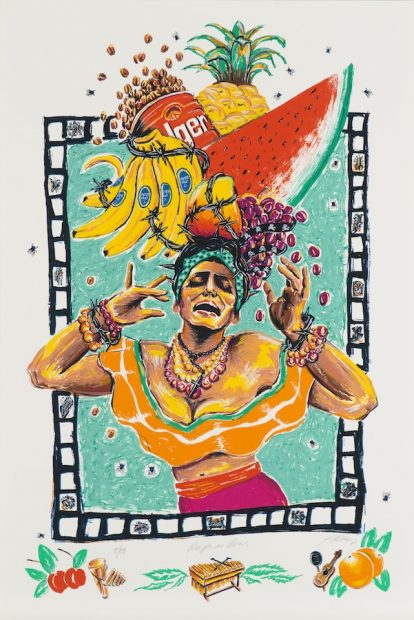

Alex Donis, Rio, por no llorar, 1988, screenprint, 38 7/8 x 26 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Gilberto Cárdenas, 2017

Anzaldúa’s concept of mestizaje also encompasses queer sexual and non-binaried gender identities. Alex Donis’ print, Rio Por No Llorar (I laugh so I won’t cry), is an example of this manifold identity. The subject in Rio Por No Llorar is the artist himself, dressed like Carmen Miranda and evoking a pose that is at once rapturous and pained. In his fruit basket hat, flies swarm around mangos, bananas, grapes, watermelon and coffee. A United Fruit Company label on the bananas references the 1928 slaughter of an untold number of striking United Fruit Company workers by Colombian armed forces who were dispatched to protect U.S. interests. Barbed wire runs through the items in the hat and also hangs across the artist’s wrists. A rosary constricts his throat. Movie film rolls across the border of the scene. Donis’ print is an implication of the continued subjection and exploitation of Latin America by the West as well as the particular suppression of queer and femme Latin Americans.

View of Arte Sin Fronteras: Prints from the Self Help Graphics Studio at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, October 27, 2019 – January 12, 2020

View of Arte Sin Fronteras: Prints from the Self Help Graphics Studio at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, October 27, 2019 – January 12, 2020

While preparing the curatorial statement for Arte Sin Fronteras, Florencia Bazzano and Christian Wurst wrestled with this question: If you are Mexican-American, how do you describe yourself in Spanish? Though “mexicoamericano” seems an obvious choice to those born or raised in the States, it foregrounds a uniquely U.S. way of thinking of the United States as the America. Elsewhere in the world, “America” encompasses everything from the southernmost parts of Chile to Canada. “To describe yourself that way would be like calling yourself Swedish-European,” Bazzano told me. This question of how you describe yourself, particularly for members of the Chicanx and Latinx communities, is at the heart of the prints on display in Arte Sin Fronteras. If the exhibition is challenging viewers to consider how they describe their identity, the works in Arte Sin Fronteras urge viewers to accept the multitudes within themselves; they offer up a path toward wholeness despite parts of ourselves that feel at odds.

Through January 12, 2020 at the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin