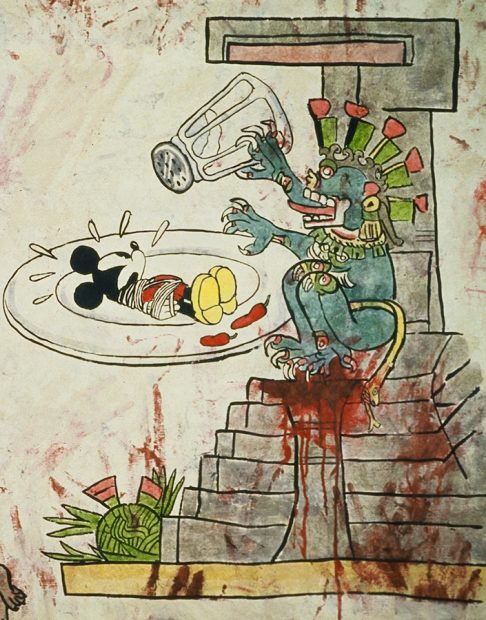

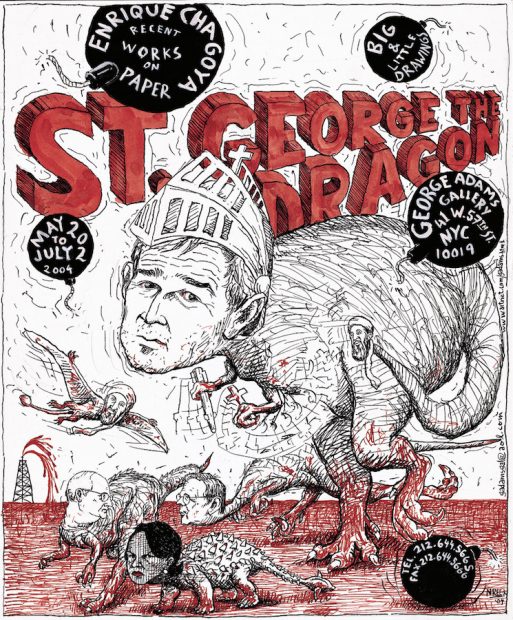

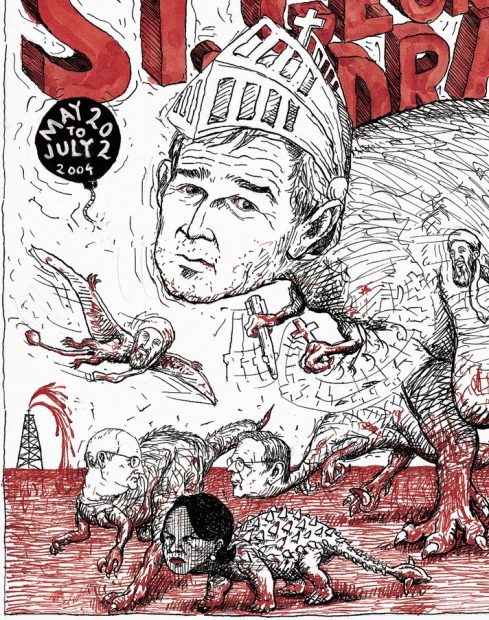

Enrique Chagoya, St. George the Dragon, 2004, ink and acrylic on paper (exhibition announcement poster), 14 x 11 ½”, collection of the artist, © Enrique Chagoya, courtesy the artist and George Adams Gallery, New York.

To read part one of this series, please go here. Part two, here.

Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

This is the third installment of Heroes and Villains in Chagoya’s oeuvre, written for Glasstire. Enrique Chagoya’s Superheroes and Super Villains (Chagoya I) begins with an overview of Chagoya’s background and formative experiences. The second part, Enrique Chagoya II: More Heroes and Villains left off with a drawing of George W. Bush and his cabinet as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in connection with 9/11 and the Iraq War. We begin here with the announcement poster for the exhibition in which that drawing appeared.

St. George the Dragon is one of Chagoya’s cleverest compositions. It is not called St. George vs. the Dragon because President George W. Bush is simultaneously the slaying knight and the evil dragon. Since — in Christian iconography — snakes and dragons are surrogates for the devil, we can regard Bush as a kind of devil, despite his human face and knight’s visor. Whatever one might say about Bush’s head, it clearly lacks the fearsome jaws and teeth that made the Tyrannosaurus rex so powerful and deadly. This Bush-headed T-rex could only kick a foe, hit it with its tail, or flail at it with its tiny hands. Thus it is a fitting symbol of the limits of U.S. power against unconventional forces.

Bush brandishes his weapons of choice — a small missile and a small cross — in his small hands. Osama bin Laden’s head sprouts from the tip of Bush’s T-rex tail. We can imagine Bush vainly trying to capture him, like a dog chasing its tail: he can see bin Laden, but he can’t catch him. Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld are smaller dinosaurs than Bush, though they have longer necks and arms (similar to Velociraptors, though larger in scale). While they also lack saurian carnivore teeth, at least their arms are long enough to permit them to put on their own eyeglasses.

Enrique Chagoya, St. George the Dragon, detail, © Enrique Chagoya, courtesy the artist and George Adams Gallery, New York.

While they stare into each other’s eyes, bin Laden silently glides right over them, in the form of a Pterosaur. This aerial capacity evokes the planes that flew into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, as well as bin Laden’s successful flight from capture in Afghanistan. Bush sees the flying bin Laden, and he furiously swings his blood-splattered cross at him (and perhaps at the bin Laden on his tail), with no effect whatsoever. A fly swatter would have been more effective, because it would have given him more reach. The bin Laden head on Bush’s tail responds with mocking laughter. Bin Laden justified his attacks on the U.S. as a holy war against infidels. Bush immediately took up the standard of the crusading Christian knight battling infidels by stating: “…this crusade, this war on terrorism is going to take a while,” as noted in Peter Ford’s “Europe cringes at Bush ‘crusade’ against terrorists,” published in the Christian Science Monitor in September of 2001.

Since both sides demonized the other, Chagoya gives even-handed saurian visual form to that demonization. To quote the film Pulp Fiction, both sides wanted to “get medieval” with one another. Hence Bush’s approval of torture, or, as his administration called it, “enhanced interrogation techniques.” Waterboarding, of course, is an old-school torture (no electricity necessary) used by the Spanish Inquisition, among others. Water torture was also used by and against U.S. forces on multiple occasions in the last century, but what is unique here is the explicit sanction of its use at the highest levels of government. As always, Chagoya questions the civilized-barbaric dichotomy that has been at the heart of Western culture since the ancient Greeks. (See discussion of Civilización y Barbarie in Chagoya II).

In the distance, an oil rig gushes blood. This detail fuses elements from two hands in Chagoya’s painting called Hand of Power (1993). One hand, inspired by Christ’s bleeding hand in Mexican retablos, gushes blood. The other hand is a gloved Mickey Mouse hand, which bears a rig that gushes oil. The sanguinary rig in St. George the Dragon encapsulates a famous anti-Iraq War slogan: “No blood for oil.” When it comes to blood, Bush’s Iraq war was a real gusher, whose fatal effects are far from over (see Chagoya II). Peter Bergen, writing in Prospect in 2006, refuted Samuel Huntington’s prediction that a “clash of civilizations” would replace the Cold War: “Most Muslims condemned 9/11, and after the attacks bin Laden’s attempt to ignite a clash of civilizations fizzled out.” Bergen also notes that Bush’s misdirected response to 9/11 had disastrous results: “It is rather the US war of choice in Iraq that galvanized anti-Americanism among Muslims.” That war simultaneously effaced Saudi connections to 9/11 and scapegoated Muslims as terrorists, a practice continued by President Donald Trump’s “Muslim ban” on immigration.

In the foreground of Chagoya’s drawing, National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice (who approved the use of torture) is an Ankylosaurus, an armored dinosaur with a spiked tail. In Mexico, corrupt, old-guard politicians are called dinosaurs. The implication here is that these monstrous, old-guard political creatures should be extinct.

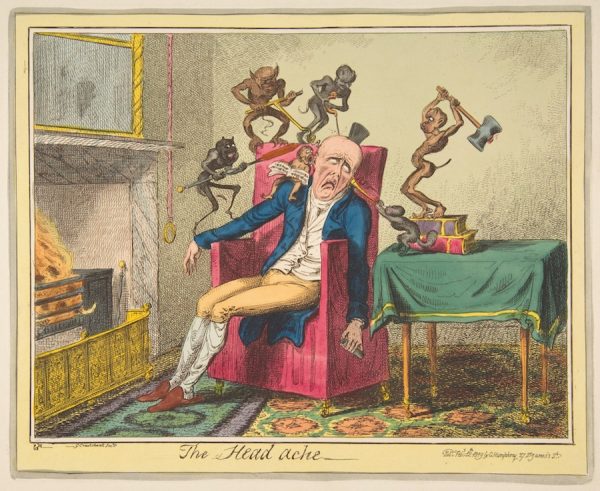

George Cruikshank (British, London 1792–1878 London), after Captain Frederick Marryat (British, 1792–1848), The Head ache, February 12, 1819, hand-colored etching, sheet 10 3/4 x 12 9/16”, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Chagoya studied the collection of the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia while he was in residence there in 2010. He chose to appropriate Cruikshank’s Head ache and transformed it into a commentary on the heated political struggle over access to health care in the U.S. Chagoya’s version of Head ache was commissioned by the Rosenbach for the printmaking festival Philagrafika 2010, where it was featured in a joint Cruikshank/Chagoya exhibition. Chagoya’s print was also included in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Infinite Jest: Caricature and Satire from Leonardo to Levine exhibition in 2011–2012.

In Cruikshank’s satiric print, a motley crew of devils besieges a man, causing an excruciating headache. A simian-like fiend holds sheet music while he sits on the man’s right shoulder and screams in his ear. A dark demon approaches with a red-hot poker. He is beside himself in anticipation of the pain he will inflict. A devil with a protruding tongue and a firm claw-hold on the red easy chair turns a mighty corkscrew whose shape echoes its own serpentine tail. The corkscrew has completely penetrated its target, and its tip is adjacent to the edge of the chair. Another imp turns a simpler drill with a wooden handle. The largest of these foul creatures energetically pounds a mighty wedge destined to cleave the man’s skull in two. The last monster has a humanoid head and the hindquarters and bushy tail of a squirrel. He blows a golden horn placed directly over the man’s left ear. With demonic pain-inflictors like these, we can be certain that the man’s medicine, which he clutches in his left hand, will avail him nothing.

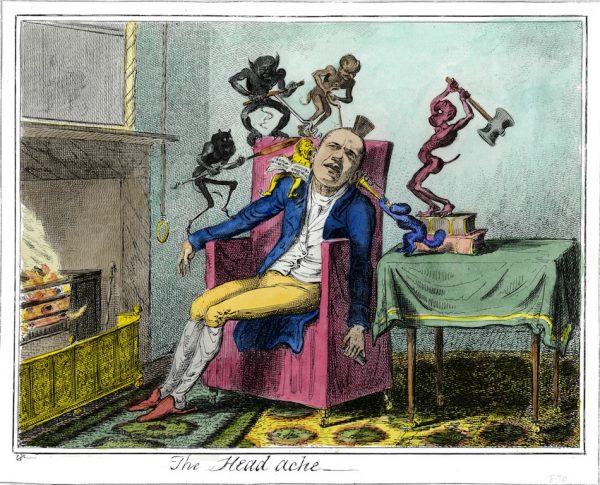

Enrique Chagoya, The Head ache, A Print after George Cruikshank, 2010, etching with digitally printed color on gampi paper chine collé, sheet 16 x 20”, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By replacing Cruikshank’s head with that of President Barack Obama, Chagoya gives specificity to both the tormentors and the tormented. “Obama is suffering from a headache caused by red and blue demons representing Republicans and Democrats torturing him,” explains the artist. He also notes that the other colored demons “are perhaps of his [Obama’s] own creation, since he committed many mistakes,” including his failure to keep his campaign promises. These mistakes “backfired,” resulting in the loss of control of the House of Representatives in the 2010 midterm elections (the 63 seats gained by the Republicans was the biggest increase since 1948). “He was trying to please God and the Devil, and in the end he did not please either,” says Chagoya.

The demons can also stand for those who oppose the expansion of health care in the U.S., and who demonized Obama’s Affordable Care Act for that reason. These very real devils cause and prolong unnecessary pain and suffering. As noted in the Metropolitan Museum’s website, the conceptually simple substitution was technically complex. Three print shops assisted in digitally reproducing the Cruikshank and digitally transferring Chagoya’s rendering of Obama’s head onto the etching plate.

When Garry Wills published the cleverly titled Obamacare: The Hate Can’t Be Cured in the New York Review of Books in 2014, Chagoya’s Head ache served as the illustration. Wills’ analysis was prescient: “Obamacare is now, for many, haloed with hate, to be fought against with all one’s life. Retaining certitude about its essential evil is a matter of self-respect, honor for one’s allies in the cause, and loathing for one’s opponents. It is a religious commitment.” Wills also posited the long-lived hatred and opposition to Social Security as a precedent for the perpetual vilification of Obamacare: “As a symbol of the New Deal, Republicans have tried to defeat it down through the decades. Paul Ryan is still at it. George W. Bush tried to use his re-election mandate to privatize it. Once such a cause is made sacred by sacrificing for it, it will remain a cult object forever.” This raises a larger issue. As Farhad Manjoo points out in a recent New York Times column, Obama, at the beginning of his term, had a majority in the House, a super-majority in the Senate, and a voter mandate in the context of a severe crisis that would have permitted him to at least attempt bold policies to make our country more equitable. Instead, he rescued the financial markets and the banks, essentially rewarding the malefactors who caused the crisis, and largely abandoned its victims, the ordinary people who lost their houses and jobs, and those who continued to see their standard of living decline even further. Even Obama’s most significant triumph, the Affordable Care Act, primarily benefits the middle class. It is too expensive for the working poor. Obama’s unwillingness or inability to deliver on promises for hope and change contributed to the election of Donald Trump. Though continuously vilified by the right, Obama seemed to lack the will to fight back, even verbally. So Chagoya’s image of Obama sitting passively while devils drill and pound his skull is a fitting visual metaphor for his failure of will and the lack of fighting spirit that characterized his presidency.

Enrique Chagoya, The Governor’s Nightmare, 1994, acrylic and water based oil on amate paper, 48 x 72”, private collection

Pete Wilson, a Republican, served as the 36th governor of California from 1991 to 1999. The Governor’s Nightmare references his support of California Proposition 187, a Republican-funded voter referendum passed in November of 1994 that called for a state-run system to prevent undocumented immigrants from receiving public education, non-emergency health care, and other social services provided by the state of California. Prop 187, also known as the Save Our State initiative (S.O.S), required law enforcement agents and numerous other government employees to investigate and report people they suspected of lacking proper immigration documentation. It also required California residents to prove their immigration status before receiving benefits. Prop 187 was the first state law to address immigration in this fashion because immigration had hitherto been considered a federal bailiwick. Opponents of Prop 187 argued that it targeted Latinos and Asians in particular. The Governor’s Nightmare was exhibited in Chagoya’s solo exhibition Borders of the Spirit at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, shortly before the election, when conflict over Prop 187 had reached a fever pitch. The painting was a topical sensation. David Bonetti, writing in the San Francisco Examiner, called his September 15 review “One Man’s Political Art is Governor Wilson’s Nightmare.” Kenneth Baker’s review in the San Francisco Chronicle was called “Chagoya’s Culture Clashes.”

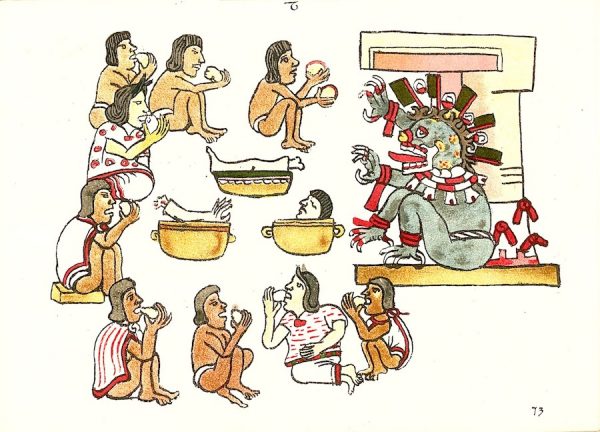

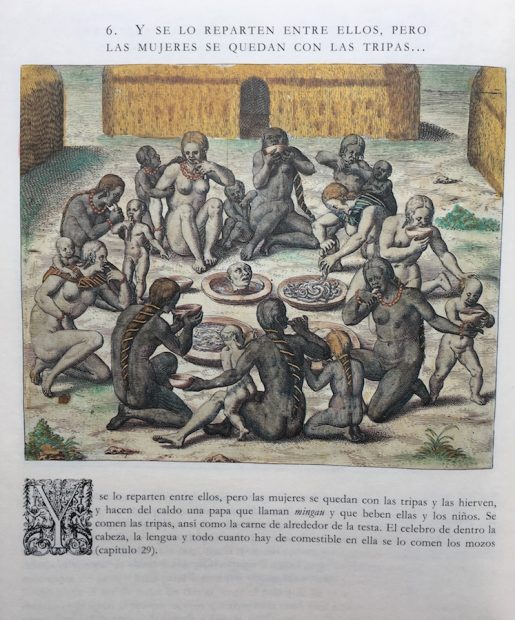

Codex Magliabechiano, mid-16th century on European paper, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence, Italy, folio 73r

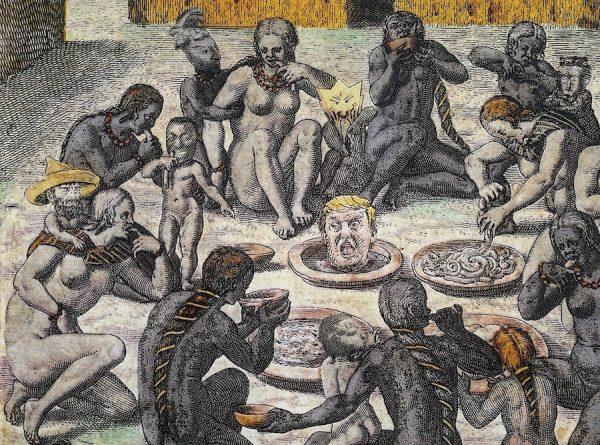

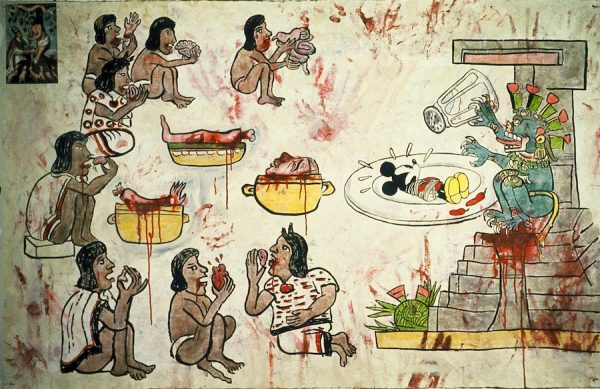

Chagoya utilized the cannibal feast in the Codex Magliabechiano (folio 73r) as his source for The Governor’s Nightmare. In the codex, the god of death Mictlantecuhtli sits on a temple altar. It is likely a decorated statue of Mictlantecuhtli: statues similar to a standing image of this god in another Magliabechiano illustration were found in the Templo Mayor excavations. Reverent diners seem poised to bite into their food. Perhaps they are waiting for the person at the top to conclude his offering of blood-smeared food to the god. Precisely what they are or will be eating is not entirely clear. I suspect it is a preliminary communion of dough balls, though it could be food wrapped in tortillas, or pieces of flesh. Since the three pots in the middle hold a human head, an arm and hand, and a leg and a foot, the cannibalistic nature of this feast is unambiguous.

Chagoya introduces features to make his scene more grisly. The god now sits on a stepped pyramid caked with gore. His knees bear fanged masks, and a human heart emblem dangles from his necklace. The grass ball of sacrifice lies at the base of the pyramid, stuck full of blood-letting implements for autosacrificial rituals. Blood drips from the pots and from the faces of the celebrants. Blood is smeared all over the page. Chagoya’s diners are about to devour specific, identifiable body parts. The man at the top is working on an entire gastrointestinal system, stomach first. The fellow next to him has an entire brain. The man behind him is literally biting the hand that feeds him. The woman below has an ear, and the man beneath her a juicy kidney. Another man holds a set of rather diminutive male genitalia. The next man squeezes a heart, causing three drops of blood to fly up into the air. The head in the pot is a dead ringer for Governor Wilson, so we can presume that he is the guest de jour at this cannibal feast (which means those must be his small genitalia in the lower left corner).

A note of cartoonish levity is introduced by Mictlantecuhtli’s meal. His outstretched claws grasp a giant saltshaker and a white saucer that holds a bound and very frightened Mickey Mouse. Two red chilies lie at Mickey’s feet because the Aztecs regarded eating bland food as a penance. Perhaps this is a commentary on the Latino boycott of Disneyland in protest against Prop 187.

Chagoya interjects a note of cultural relativism by including the Mexican painter Juan Correa’s Allegory of the Holy Sacrament (c. 1690, Denver Art Museum) in the upper left corner. Here Christ squeezes grapes into a dish and into a large vat from which sheep (the Christian flock) will drink. The grapevines spring from the wound in Christ’s chest, and his cross stands in the background. Correa’s painting represents transubstantiation: the miraculous transformation of wine to Christ’s blood through the sacrament of communion. Through this device, Chagoya affirms that Christians, too, are imbibers of sacrificial blood, albeit in symbolic form.

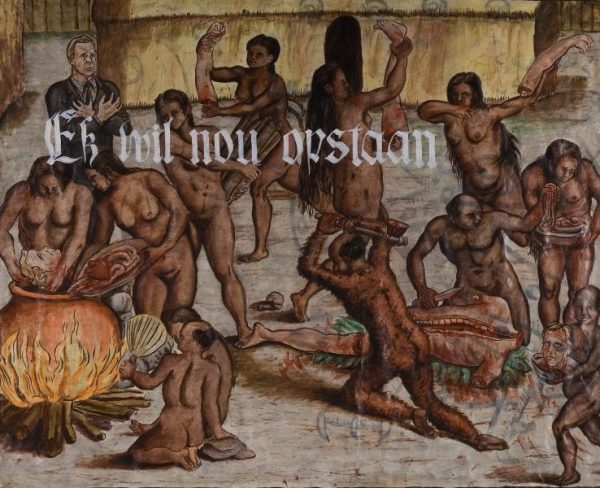

Enrique Chagoya, Xenophobic Nightmare in a Foreign Language, 1994, acrylic on amate paper, 48 x 70”, collection of the Des Moines Art Center

Chagoya made another painting on amate paper in 1994 that featured Governor Wilson as the main course of a cannibal feast. Titled Xenophobic Nightmare in a Foreign Language, Wilson is pictured three times, in various stages of meal preparation. In the upper left, he is in suit and tie — clearly overdressed for this solemn occasion — with his hands crossed over his chest in dreadful anticipation. In the right foreground, his torso is lying on a bed of leaves. His head and three of his limbs have been hacked off. A man who is dressed in the flayed skin of another victim (which makes him a devotee of the Mesoamerican god Xipe Totec) is completing the dismemberment of Wilson’s right leg. On the left, a man is fanning the flames beneath a large caldron, while two women deposit his head, heart, and entrails into it. Chagoya’s primary visual source is a Theodore de Bry print of a cannibal barbecue. Chagoya redeploys the fence, the hut in the background, the man fanning the flames, and he utilizes several of de Bry’s poses and gestures. By substituting a cauldron for a barbecue, Chagoya situates the scene in Mesoamerica rather than Brazil (the location identified in de Bry’s print) or the Caribbean. Chagoya also makes the celebrants look indigenous. De Bry had never been to the Americas: he had no idea what people there looked like, and he made no effort to break with Western conventions. Chagoya overwrites this scene with an inscription in white letters in the Afrikaans language used by the apartheid regime that took power in South Africa in 1948. This white supremacist system was predicated on racial segregation and it forced people of color to utilize passes when they traveled. It ended definitively in 1994, when people of all races were allowed to vote. Just when apartheid had ended in South Africa, Chagoya feared that Prop 187 would inaugurate a pass system in California that would oppress and discriminate against people of color. His inscription translates as “I want to wake up now.”

After it received a majority of votes, Prop 187 was immediately challenged on constitutional grounds. A temporary restraining order blocked most of its provisions days after its passage, but both sides vied to win in the court of public opinion. A federal judge deemed Prop 187 unconstitutional in 1997 and followed up with a permanent injunction, a decision Governor Wilson appealed. Wilson was replaced by Democratic Governor Gray Davis in 1999, who ended the ordeal by withdrawing Wilson’s appeal. Wilson declared in 2015 that he would still support Prop 187 in the same manner. Most commentators believe the racially divisive effects of Prop 187 contributed substantially to the marginalization of the GOP in California. Politico reports that registered independent voters now outnumber registered GOP voters. Some experts expect that President Donald Trump’s divisive racial policies will likewise have significant negative consequences on the GOP’s popularity on a national level.

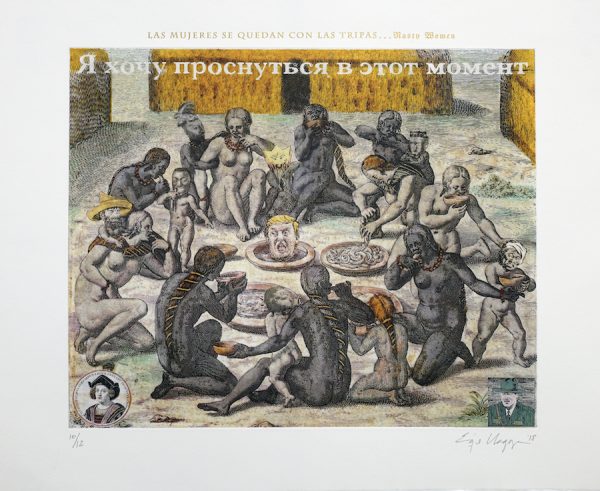

Enrique Chagoya, The President’s Xenophobic Nightmare in a Foreign Language, 2018, copper plate photo etching with digitally printed color, UV-cured acrylic, and stamped gold foil, 22 x 25”

De Bry is once again Chagoya’s visual source for this cannibal feast. This time he utilizes a de Bry etching of (purportedly) Brazilian native women and their children. Chagoya follows a hand-painted version in which half of the women are painted dark. As noted by Nick Stone, Chagoya thought a print filled with women was appropriate “because of all the misogyny surrounding this president and his supporters.” Chagoya is also moved by female agency and opposition to Trump and other abusive men: “…it is due to women that things are changing – whether it’s the women’s marches, Stormy Daniels, or the Me Too movement taking down powerful, predatory men.” To underscore this opposition, “Nasty Women” is stamped at the top of the print in a color mockingly described as “Trumpian gold foil.” In the final presidential debate between Trump and Hillary Clinton in 2016, Trump referred to her as “Such a nasty woman,” a quip that sparked a resistance movement against him. Chagoya added images of Christopher Columbus and a stock border agent character in the lower corners of the print.

Theodore de Bry, engraving depicting cannibalism in Brazil, originally for volume 3 of Collected travels in the east Indies and west Indies, which reprinted Hans Staden’s account of his experiences in Brazil, 1594. Chagoya used a hand-colored version of the print from America / Teodoro de Bry, published in Spain by Editorial Siruela S.A. in 1992. Note that the watercolorist failed to color a leg belonging to the woman in the center foreground (it almost looks like her child has sprouted an adult leg). This error inspired Chagoya to put a black head on a white child.

In addition to Trump’s head, Chagoya also replaced the children’s heads with non-Western characters. The straw hat-wearing man is a Mexican bandit from a 1930s racist comic book. The triangular star face (above Trump) is from a box of Chinese fireworks. Muslim and African stereotypical heads were taken from a Tarzan comic book. Chagoya also added the head of Pakal, lord of the Maya city-state of Palenque, which is based on a famous stucco portrait. “The idea,” says Chagoya, “is that they are all mixed together in the president’s racist, xenophobic, and misogynist nightmare.”

The white inscription — this time in Russian — translates as “I want to wake up at this moment.” Apparently Trump has, which is why he is screaming.

The cannibal paintings discussed here are just the tip of Chagoya’s artistic cannibal iceberg. Yet, despite appearances, Chagoya assures me that he is not obsessed with cannibalism. He explains: “My use of cannibalism is metaphorical to make fun of the stereotypes of the ‘savage’ immigrants that come to destroy our ‘civilized’ society. It’s kind of making fun of the dichotomy made by the Greeks between ‘civilization and barbarism’ (for everything outside Greece). This way of thinking was later translated to the Americas by the conquistadores and pilgrims.” Thus we have sampled three meaty courses of cannibalism as satire, and I think they are all delicious.

As for what Chagoya hopes to achieve with his art, that question is answered in his 2018 book Aliens Sans Frontiéres (a play on Doctors Without Borders). He considers it “kind of arrogant” for an artist to think that he/she could “change the world with art.” In that case, Chagoya says, he would simply “paint a beautiful world.” He instead urges direct forms of engagement. Chagoya does, however, hope that his art, in addition to exorcizing his own fears and anxieties, “can create thought-provoking situations” and also create dialogues or bridges — including with or to people outside of the art world. “Some of the best experiences in my career were talking to people outside of my art bubble,” declares the artist.

In his 2001 interview with Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Chagoya expresses hope that the misuse of power can be ended and that the destruction of the world can be averted. “Otherwise,” he adds, “we’ll just join the dinosaurs in the list of extinct species.”

In conclusion, I would like to consider Chagoya’s assessment of Goya, as reported by Diane Manuel in 1997. Chagoya values the master’s “constant effort to find light through what is dark,” which serves as a “profound contrast to the nihilism of the late 20th century.” We must say the same of Chagoya.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator. His next curatorial project, “The Day of the Dead in Art,” opens at Centro de Artes (the former Museo Alameda) in San Antonio on October 24. This revisionist exhibition argues that much of the received knowledge about Day of the Dead is incorrect. It features more than 100 works by more than 50 artists, including a print by Chagoya.