I wish I had a river I could skate away on.

– Joni Mitchell, River, 1971

One of the the things that allows great art to resonate with us is that it taps into something that feels familiar and true that many of us haven’t been able to articulate. And while the impulse or urge to ‘disappear’ may not be universal, I’d say that it’s very common and very human.

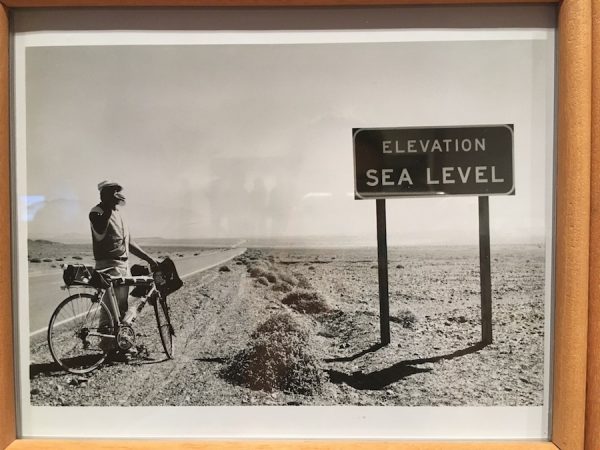

But the social permission to undertake that fundamental human need — to break from hard physical, mental, or emotional realities and enter a undefinable space (or void), one inaccessible to others — is disappearing. We’re expected to be present and accounted for, we’re expected to be on, all the time. Which, for some of us, makes the idea of disappearing even more seductive.

Disappear means different things to different people, of course. There’s one day left for a show at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth titled Disappearing—California c. 1970: Bas Jan Ader, Chris Burden, Jack Goldstein. While this isn’t exactly show review, the show is what led me to think about what ‘disappearing’ means to us right now.

All three of these artists during their prime years (they’re all dead) explored varieties of obliteration, and its inherent risks: a disappearing of the art object; of the role of the institution or gallery as a way to show or sell work (and therefore an erasure of market forces on art); of the ego; of physical presence; of a body’s basic needs. In the case of Ader, of course, he disappeared himself prematurely and permanently when, under the cover of art, he launched himself into the Atlantic on a comically tiny sailboat and was never seen again.

The exhibit’s title includes more explanatory detail than is typical. It pointedly includes the artists’ names, almost as if it wants to get out in front of any identity-based criticism of a show about three dead western white guys in a major museum, which might raise a few eyebrows in our current climate. But the independent curator, Philipp Kaiser, also includes both a specific era and place: California in 1970. (The show title’s subheading could read “Look, there’s a reason Lee Lozano, Tehching Hsieh and William Pope L. aren’t included.”) I don’t mind. Sometimes a thesis, when it’s this broad, should be this narrow in its delivery. We’ve romanticized Burden, Ader, and Goldstein with good reason; they all went about things in an unapologetic, aggressively maverick manner that the art world could always use more of, and yet which is always mysteriously scarce.

Or not so mysteriously. Keep in mind that some of their work, and in particular many of Burden’s early very physical works and some of Ader’s, couldn’t take place today at all, given the guerrilla nature of it. Attaching today’s extensive insurance riders and legal teams, security firms and signed releases would undermine an essential spirit of their actions. Nowadays, genuine individual risk-taking isn’t just frowned upon; it’s criminalized. So this show is not just romanticizing the artists. It’s also nostalgic for a time when art like this could be made and understood.

Chris Burden, You’ll Never See My Face in Kansas City, Morgan Gallery, Kansas City, MO, November 5-7, 1971, 1971. Ski mask, Overall (case): 5 1/2 × 17 × 12 in. Private Collection © 2018 Chris Burden / licensed by The Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Around 2009 I was giving a guest lecture at a university — something about the rapidly changing art world in the digital age — and during the Q&A an art student asked about whether having an online presence was a risk to the integrity of the artist and the art. I don’t think of myself as particularly prophetic, but I answered that I believed that very soon artists, and all other people, would be considered suspicious or even punished for not having an online presence. Which of course, now, often feels true. If you’re not online, in the eyes of many you don’t exist.

And for digital natives and older generations alike, being overlooked or forgotten (disappearing even for a minute) seems to be intolerable. As a species, we know that exile – being cancelled or self-cancelling — equals a kind of death. Right now, digital obliteration is the penultimate disappearance. And yet… people are leaving Facebook and Twitter en masse.

But we hesitate to dump our social media profiles. And maybe that’s because we’re attempting to stay present when so much of what we value is disappearing by the day. The health of the planet, job security, basic decency, democracy. In very short order, we’re going from being a society that could count on the existence of polar bears and bats and bees, a basic social contract, and privacy, to being a society that can count on none of these things, and not much else, either.

But it’s still within us, this need for escape, or a need to annihilate the self every once in a while, if anything to see what version of ourselves comes out the other side. We need breaks from home life, work life, the hamster wheel of obligation and responsibility. How we go about it is sometimes a personal choice, though sometimes the route is chosen for us, against our will or intention. To quote a character played by David Lynch in a key episode of Louie:”You gotta go away to come back.” (I won’t touch on the irony here.)

On some level I think we all understand that invisibility is a kind of power. Most billionaires are fiercely private for a reason. And survivalists are a type who have located and cultivated the urgency behind a desire to flee a hostile world. Things are rough out there, and getting rougher. Let’s get out of here. We can obliterate ourselves geographically, or digitally. We can do it through drugs and booze, sex, bankruptcy. But we’re reminded, constantly, that most forms of self-abnegation come with costs that are likely permanent.

I don’t think it’s such a bad thing to ask ourselves what Burden, Ader, and Goldstein would have thought about, say, Instagram if they had lived to witness its demands — if they had been confronted with how hungry the world seems to be (especially the online world) for people who build themselves up, performatively, in order to be ever-present. I also think we know what these artists’ answer to that demand would be. (I’d place a bet on “Screw that.”) There’s a reason we’re still talking about them. Disappearing is risky. But it’s also human.

‘Disappearing—California, c. 1970: Bas Jan Ader, Chris Burden, Jack Goldstein’ at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth through Aug. 11, 2019.

1 comment

Thank you for the article. The show is magnificent. The video ” The Fall 1″ Bas Jan Ader – 1970 presents perfectly the counter-intuitive disappearance of the physical self in a continuous loop of pain.