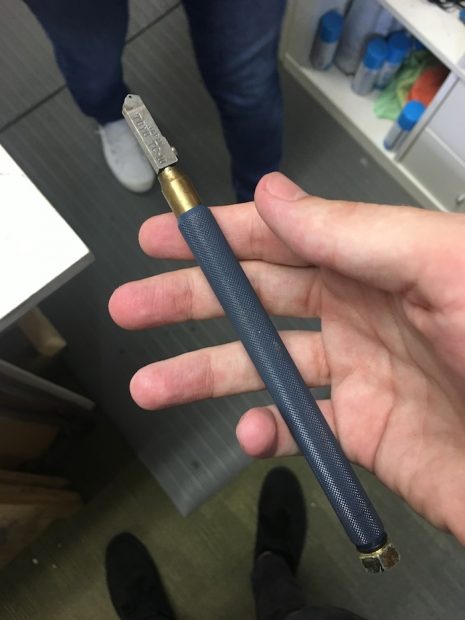

In the detached garage of a Tudor-style house off lower Greenville Avenue in Dallas, Michele Grojean Blaker talks me through her immaculately organized collection of stained glass tools and materials. The workshop is called Grojean Glass Studio, and there are panels of vintage glass from various producers like Kokomo, Spectrum and New Antique. She’s familiarizing me with the terms unique to the medium, like lead came, the metal lining that holds the glassine composition in place. She’s even got a custom-machined carbide wheel glass cutter — a scoring utensil for breaking glass sheets into specific designs — that she inherited from her father.

Full restoration; removed all 50 individual pieces, re-leaded them, replaced broken glass as needed, reglazed back in place. Photo: Michele Grojean Blaker

The specific neighborhood, Greenland Hills, is a subsection of Lower Greenville that runs from Greenville Avenue to Central Expressway, McCommas Boulevard to Vanderbilt Avenue. The more intact ‘Tudor’ and Craftsman style houses in the area feature stained-glass accents and artful windows that date back to the 1920s. Blaker is a fan and custodian of many of these houses’ windows, and she lives in the neighborhood. A former reporter, she’s since become an artisan. She’s enamored with glass’ ability to transform light. “That’s what we’re trying to do as artists,” she explains, “manipulate that light to be beautiful.” She learned the craft after her father took an interest in it late in his life, which is where some of her materials come from, specifically the custom-machined pieces for cutting and milling designs into lead came.

Blaker is handy with knowledge about conservation efforts in the area, citing regulations that require builders to keep like with like. If a property was originally outfitted with stained glass, it must have a stained-glass piece after any and all renovations. The building regulations for these streets mean that during development booms, the facades of these residences remain must intact even if the interior is gutted. The houses of Greenland Hills (a neighborhood referred to by Dallasites as ‘The M Streets’) have remained notably more intact than most of their Lower-Greenville counterparts. Blaker has photographed almost every window piece in the neighborhood, and plans to post them on her studio’s website. The idea is to give those who are interested in the aesthetic integrity of the neighborhood a online destination to view the admired style. And new builders could use her site as a resource to implement new designs that won’t feel out of place.

Stained glass (often referred to as both an art and a craft) is burdened with some common misconceptions. Namely, Blaker says, homeowners often don’t know about the maintenance that comes with keeping the glass properly sealed. Weatherproof putty rests between the lead came and the individual window panes, but it needs to be replaced about every 25 years. It’s a simple fix, and in her workshop during my visit, Blaker demonstrates how to roll it into the crevices of the lead. The lead came itself is another issue; about every 100 years the piece needs to be re-leaded entirely. These are merely rules of thumb. Climate conditions make a difference on the rate of deterioration, not to mention whether the piece is designed to handle weight and stress across individual panes.

Blaker understands that for some, the expense is a turn off. “People don’t want to pay. I get it. It’s cheaper to get all new windows. But what’s the loss?” It may cost less to replace old with new, but it seems to me that much of the appeal (and therefore the value) of the houses and the neighborhood is original character and architecture. Blaker goes on to cite common complaints about stained-glass windows: they can be drafty when in poor condition, and homeowners argue that it’s more energy efficient to replace them with a new windows. I wonder if the carbon cost of mass-manufacturing windows and shipping them here from China is lost on these homeowners. To me it seems like a shirking of responsibility for the integrity of an older house.

Stained glass is ripe territory for a layered discussion on the meaning of ‘integrity.’ Blaker gestures over the anatomy of a vintage window piece undergoing restoration in her shop. Architectural structure and load-bearing ability are intrinsic to the design of a piece. Care must be taken when working and reworking the lead and the putty that hold it all together, lest the window’s integrity degrades beyond saving and the entire window must be, essentially, reconstructed. So, too, is the aesthetic integrity of the neighborhood at risk when we take these key aesthetic elements for granted during waves of building booms and renovations. How important are these windows as motifs of the neighborhood and the city?

Blaker, when regarding these issues, quotes Frank Lloyd Wright: “Ornament cannot be divorced from its setting and still have meaning.”

“He’s talking about the glass being moved and treated as art on its own, rather than it being an intrinsic part of the architecture,” she says.

Michele Blaker’s stained-glass studio and restoration workshop, Grojean Glass Studio, is in Greenland Hills, Dallas. She can be reached for inquiries on commissions, repairs, and restoration through her website. More information on the conservation guidelines for Greenland Hills can be found here.