Monet: The Late Years, the exhibition currently on view at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, is the culmination of the museum’s years-long relationship with Claude Monet’s paintings. In 1994, the president of the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia challenged the dying will of its founder Albert Barnes, which forbade the Barnes from ever allowing art in its collection to leave its home gallery. The Foundation won, and as a result the private art collection was permitted to travel outside of its home in Marion, near Philadelphia, for the first time. By no accident, the Kimbell was one of the stops on that historic tour, and the exhibition Impressionist Masterpieces From The Barnes Collection: Cézanne to Matisse, opened to blockbuster success.

Two of Monet’s paintings were part of the Barnes Collection show: Madame Monet Embroidering and The Boat Studio. Before Masterpieces, the lone Monet painting in the Kimbell’s collection was La Pointe de la Hève at Low Tide, painted in 1865, almost a full decade before another painting of his, Impressions, Sunrise, would debut at the former studio of photographer Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, a.k.a. Nadar, and launch the Impressionist movement.

It is from this strong connection to Monet and Impressionism that The Late Years makes its way to the Kimbell. With 51 paintings, large reproductions of Monet’s studio and property, and a short silent film of the artist painting in his garden, the show is a comprehensive examination of Monet’s work made from his mid-70s until his death at age 86 in 1926. As the Kimbell’s website states, the show “…focuses on the period when the artist, his life marked by personal loss, deteriorating eyesight, and the threat of surrounding war, remained close to home to paint the varied elements of his garden at Giverny.”

The Late Years comes not long after another show of Monet’s at the Kimbell, which examined the artist’s first decades of painting. Monet: The Early Years opened at the Kimbell in October, 2016, and was conceived as a two-part series of exhibitions curated by George T. M. Shackelford, deputy director of the Kimbell, with the collaboration of colleagues at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, where it debuted at the de Young Museum there.

Claude Monet, The Japanese Footbridge, 1899. Oil on canvas. Gift of Victoria Nebeker Coberly, in memory of her son John W. Mudd, and Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg

The Late Years is an exhibition of ‘pretty’ paintings, although they haven’t always been considered pretty. That seminal exhibition at Nadar’s old studio (which came decades before the works in the current show) was heavily criticized in the satirical magazine Le Charivari by the art critic Louis Leroy. In a translation of his criticism by the website Arthive, Leroy wrote of Monet’s painting Impressions, Sunrise: “Impression — I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it … and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is more finished than this seascape.” Oof!

In the century since the Le Charivari article, Monet’s paintings are as popular and successful as ever, if scheduled exhibitions and auction prices are any indication. A painting from his Meules (Haystack) series, for example, fetched a whopping $110 million earlier this year in an auction at Sotheby’s, besting a previous record sale of the painter’s work at Christie’s last year, where Nympheas en fleur sold for $84.6 million. And there have been at least four exhibitions which include Monet’s works over the past 12 months in the US alone (Telfair Museums in Georgia; Worcester Art Musem in Massachusetts; The Frist Museum in Tennessee; and the Denver Art Museum in October).

In considering The Late Years, I’m reminded of the late Czech philosopher and media critic Vilém Flusser’s theory about art criticism in which he discusses points in the shifting value of a work of art, when it moves from being considered to beautiful to pretty. In the compendium Vilém Flusser: Writings, he writes:

“The more convenient the reception of the information contained within a work of art is, the prettier that work is. If one applies the basic law of communication, which states that information and communication are inversely proportional, one may measure how much a specific work communicates: the better it communicates (the more redundancies it contains), the less it informs. In other terms: the easier it is to decipher a work of art, the prettier it is, and therefore the more successful.”

Because of our familiarity with Monet’s work, his paintings have become easier on the eyes (and brain). It is not radical to suggest that his complete body of work has moved from ‘ugly’ in the days immediately after Leroy’s article, when they were new, to ‘beautiful’ after the full embrace of Impressionism. Somewhere along the way, they moved to ‘pretty’ — let’s say post-1945, when the terror of zip paintings and Abstract Expressionism became the new and unfamiliar. Then Claude Monet’s prized water lilies started to feel kitsch in the 1980s and beyond, evidenced by the consumer explosion of his lilies blooming across dorm-room poster prints, umbrellas, mouse pads, t-shirts, and coffee mugs.

Claude Monet, The Artist’s House from the Rose Garden, 1922-24. Oil on canvas. Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris France

What is radical about this transformation over the past century is that we are at a moment when these paintings are again ‘ugly’ to the art world due to kitsch overload — and when also the newest art, as our response to the new and terrifying, is also terrifying and ‘ugly.’ But Flusser reminds us about this truth: “All those who experience the tremor of beauty (in other words, every one of us) know by intuition what is implied in the terror of newness.” This newness, Flusser concludes, will slowly flow again towards familiarity, and complete (and close) the loop from ugly, to beautiful, to pretty, to kitsch, and back to beautiful again. Or as Flusser puts it: “…even the most improbable situations created by art will in the long run become habitual — will no longer be experienced as being hateful and ugly.”

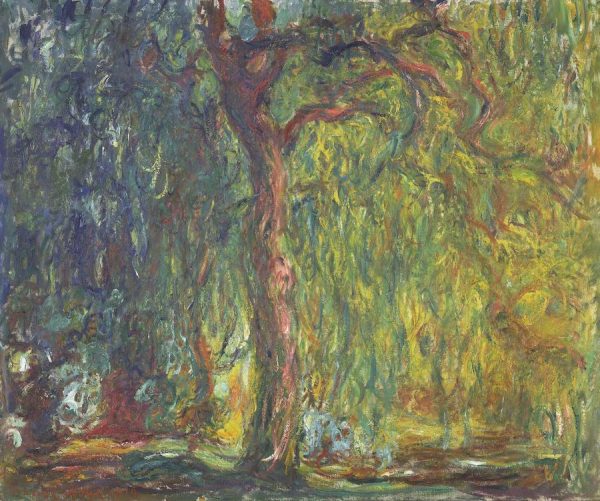

This is where things are with The Late Years. We are familiar with the water lilies. They communicate through familiarity, and require little deciphering. They are kitschy and border on ugly, where they are on the verge of evoking the terror of the new. But it is by revisiting a painting like Weeping Willow, the Kimbell’s newly reframed Monet (acquired a couple of years after the Barnes Collection show) that the beauty and the sublime in the terror of the new peeks through. It is in these wild swirls of light and dark, as the artist grapples with light as his sight fails him, that we are again terrified. And it makes us reconsider Monet. What was so familiar fades, if only for a moment, back into mystery.

Artists and painters would do well to find a way back to these paintings. Under the eye-roll response that some may bring to this exhibition is the potential for true discovery, or rediscovery of a painter whose mastery has also come full circle, and whose dedication and trust in his subject has embedded these paintings with enough complexity to survive another cycle of ugly, beautiful, pretty, kitsch.

Through September 19, 2019 at the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth