You probably haven’t even noticed. But if you’re headed toward downtown Houston on West Gray Street near Gillette, you’ll see a new five-story apartment building. It’s called Dolce Midtown. It has a pool. Outdoor spaces with “stainless steel grills.” The website calls Dolce Midtown “your urban oasis” and claims that the Med Center, Hermann Park and museums are “literally minutes away.”

It’s easy to make fun of it. There are five-story apartment buildings just like it in Denver and Austin and Seattle, but it would be hard to tell which city they’re in if you didn’t already know. Does Dolce Midtown know?

Because this is not Midtown.

It’s Fourth Ward. Freedmen’s Town.

But you might not know that, not from driving along West Gray — not if you don’t already know Houston. And many of us don’t, I don’t think, as we newcomers move in, relocating here to earn a degree or start a new job. Knowing only, really, that this is where the opportunity is, so we came.

That’s what I did.

But I have learned that this isn’t Midtown. And Dolce Midtown, stretching across two city blocks, obscures that. As does Proguard Self Storage. As does I-45. As does the Federal Reserve.

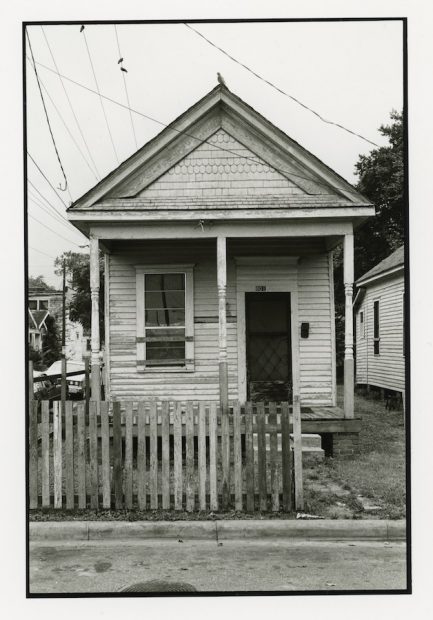

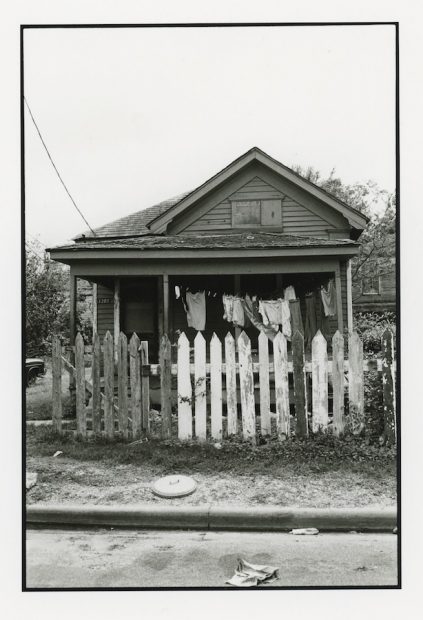

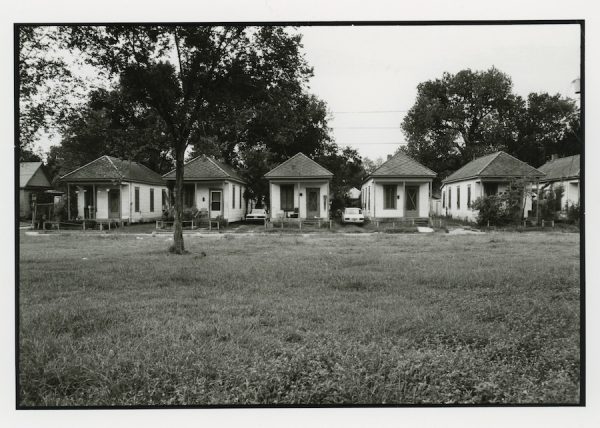

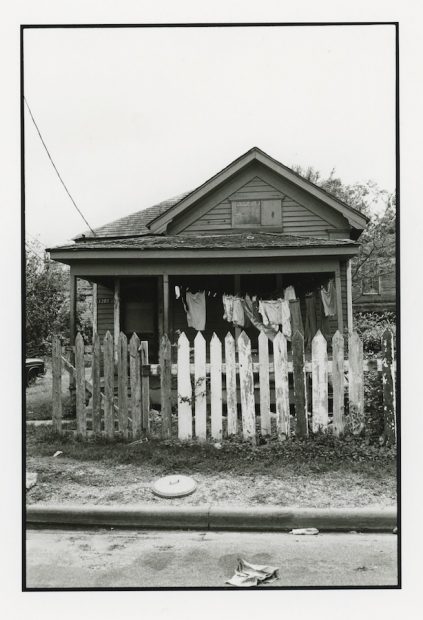

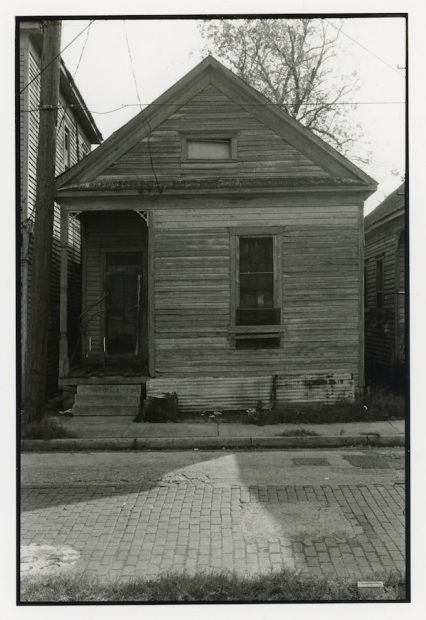

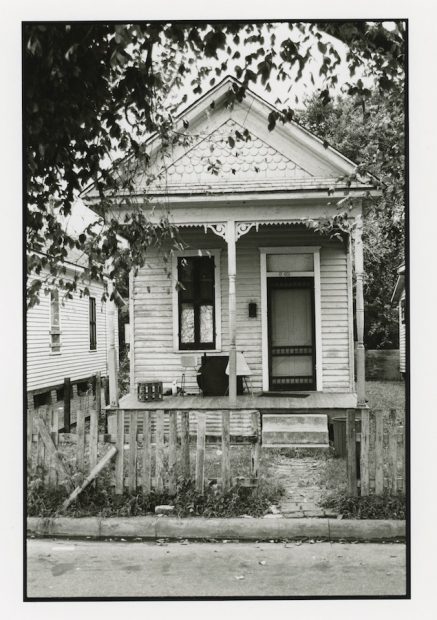

But if you walk north on Gillette toward Victor, to the back of the Dolce Midtown property, you’ll see a row of shotgun houses, saved from demolition but no longer habitable. It’s one of the more jarring images I’ve seen in Houston: the juxtaposition of the scale and the materials — the new stucco; the old, almost fuzzy shingles; the “Now Leasing” sign and the “No Trespassing” ones.

These shotgun houses, which the Houston architectural historian Stephen Fox has dated to as early as 1914, are part of the historic Freedmen’s Town that Ashlyn Davis says is “almost gone, in a physical sense.”

Houses just like these show up among the works in the show that Davis, the executive director of the Houston Center for Photography, has curated this summer, titled Elbert Howze: Motherward, 1985, up through July 7. The show, collecting the late Howze’s extraordinary, intimate portraits of Freedmen’s Town residents, along with his architectural photography, writing and archival documents, is an attempt to slow down that disappearance.

Howze, a native of Detroit and a Vietnam veteran, moved to Houston in 1973. Here, he earned several degrees, including a master’s in photography, from the University of Houston. In 1985, he started making portraits of residents of Freedmen’s Town, which, he wrote at the time, seemed “a place of neglect and decay, which appears to be deliberate by plan.” He would collect the portraits and write in a book that Barbara, his wife, took with his other work to HCP in 2015 after his death.

Opening Howze’s portfolio and the boxes of his photographs and seeing the book, Davis says she had a “visceral feeling.”

“I knew this was important for Houston,” she says. “Houston doesn’t tell the story often enough of what Freedmen’s Town is and what it means.”

Maybe you’ve heard about the bricks. Maybe you’ve been forwarded the essay about the demolition of Allen Parkway Village. Maybe you’ve walked around behind Dolce Midtown and read one of the historical markers posted behind the chain-link fences. For a newcomer like me, an outsider, Howze’s photographs are an invitation to reckon with the story of Freedmen’s Town.

Maybe you know that about 600 people emancipated from slavery settled here in the 1870s, as the historian Tyina Steptoe writes. Freedmen’s Town was once the center of black life in Houston, with professionals setting up professional practices and local businesses, forming congregations for worship, forming community.

But maybe you’ve heard about the way that the city soon targeted the community for the relocation of the red-light district, moving it here from the part of downtown that is now the Theater District. And maybe you’ve heard about how Freedmen’s Town was redlined in the 1930s as “hazardous,” leading to decades of disinvestment and starving families of the possibility of building generational wealth through homeownership. This is just the beginning of what Howze would mean in the ‘80s when he wrote about “neglect and decay … deliberate by plan.”

“This is a community that’s been systematically denied the social services that everyone else has had access to,” Davis says.

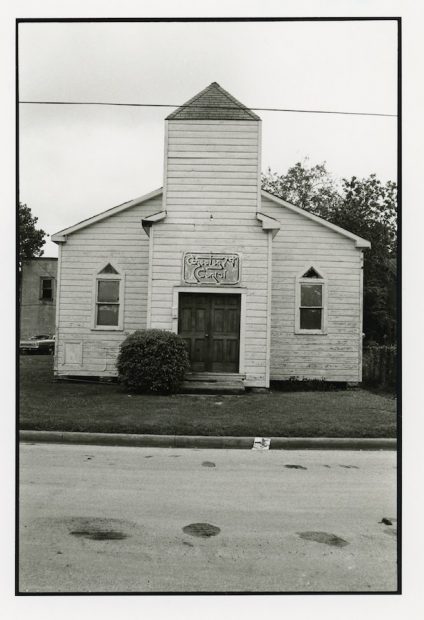

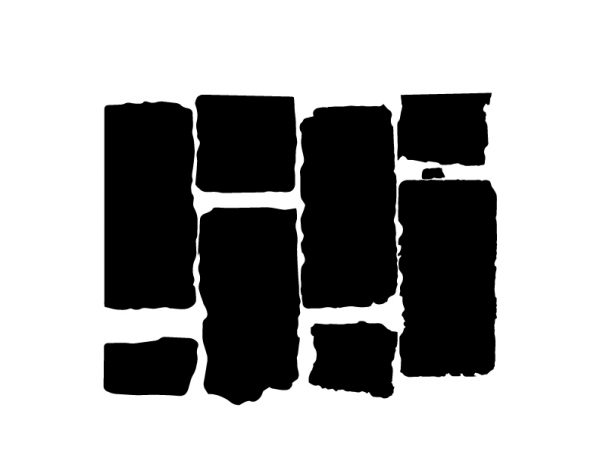

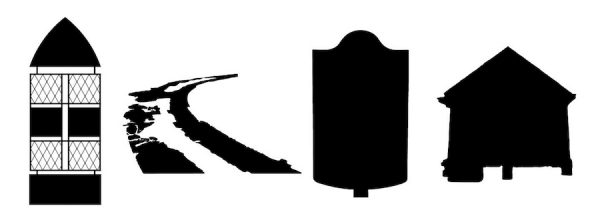

This year, Preservation Texas included Freedmen’s Town and other Texas freedom colonies on its list of the state’s most endangered places. What remains, for those of us who don’t know, who can’t ever know, are the faintest of artifacts, Howze’s photographs, the shapes of memory provided by the built environment — now almost archeological remnants — that give the rest of the us only suggestions of the place that this was, the dignity of the lives that made this a place. It’s the rectangles of those bricks on Andrews Street laid by masons when the city wouldn’t pave the streets. It’s the triangular gables of the shotgun houses on Victor Street. It’s the peaked windows of Bethel Church, almost lost to a fire, but preserved as a public park. It’s the patched-over arc of the streetcar tracks that used to connect the neighborhood to downtown. It is, as Fox writes, the narrow streets that gives this place “spatial distinctiveness.” He means that it is as intimate as any in the city.

These shapes are that much more important for being so faint. HCP is not a collecting institution, but Howze’s photos will become part of the African-American Library at the Gregory School in Freedmen’s Town. Davis believes that they need to be at the Smithsonian, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. They help us see what the forces that have shaped our cities tend to obscure.

As Howze wrote about his photographs: “This is not about the skyscrapers that line the skyline or the perimeters of this place. It’s about the spirit and determination of these people that live there.”

For newer Houstonians like me, the perimeters of this place, the shapes I can still see, ask me to imagine that spirit, to confront the reasons why and the ways that it has tried to be erased. It is so faint, now, but it is still there.

Through July 7, 2019 at the Houston Center for Photography