TTU Land Arts on the Road: dinner with guests Sofia Krimizi and Kryiakos Kryiaku from Texas Tech, Whitney Tassie (and family), Alana Wolf, Jessica Breiman and Todd Samuelson of the University of Utah

The Museum of Texas Tech University is an apt embodiment of the university as an institution: impressive from the outside, it’s a jumble of competing interests on the inside, from dinosaur exhibits to fashion and textiles (sometimes even in the same room), but with hidden gems throughout. One of those hidden gems at TTU is the Land Arts of the American West program.

Described as a “semester abroad in our own backyard,” Land Arts is led by Chris Taylor of the TTU College of Architecture (more on the program and its history can be found in this New York Times profile), and there is a sister program operated out of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Over the course of the semester, Taylor leads students over thousands of miles to visit and investigate sites throughout the Southwest, from earthworks landmarks — like Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, Michael Heizer’s Double Negative, and Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels — to culturally important landscapes like Chaco Canyon and White Sands in New Mexico, and lesser-known land-use sites like Jackpile Mine (NM) and Muley Point (Utah). Students return to Lubbock crusted with salt and grime from weeks of camping in the desert. They regroup, wash up, and make work.

The resulting work from Land Art’s 2018 session can be viewed at the TTU Museum until April 22, tucked in a small gallery in the back of the museum, in a vitrine-like, glass-box of a space branded “Leonardo’s Kitchen” by a repellant Mona Lisa sign augmented with neon lights. (I can just imagine the long committee hours spent coming up with that gimmick.) At first glance, it looks like it will be a café at the end of the hall. But it’s a gallery, inaugurated in 2017 as a space to show research and art by TTU students and faculty, and to showcase the crossover between “research and creative activities” at the university, according to the museum’s executive director, Gary Morgan, who took on the job in 2015, and reportedly has already left the post.

Prior to 2017, the annual Land Arts exhibition took place in an old warehouse, now defunct, just outside the LHUCA/CASP campus a few miles away, and I can’t help but wonder what the Land Arts exhibition looked like in that environment. Not that there’s anything specifically wrong with Leonardo’s Kitchen as an exhibition space — but a warehouse, I expect, would be more apropos, more atmospheric, for the work that results from the program.

Maybe I feel that way because of The Combine. The Architectural Workers Combine is a warehouse way out on a lonely stretch of Avenue A on the far east side of Lubbock, whose neighbors include a giant cottonseed oil mill, a truck wash, a taco shop, and a vacant lot. And indeed, it is like walking into a warehouse-sized Robert Rauschenberg, though I don’t think that’s what it’s named for. Chris Taylor has sectioned off some living quarters that resemble a recording studio with big windows between the rooms. The rest of the warehouse serves as the headquarters for Land Arts, space for the activities of the College of Architecture, and the location of the annual “long table” dinner to celebrate the Land Arts exhibition — with 99 seats, the dinner is the best collection of luminaries Lubbock has to offer, tucking into curry and rice, drinking Dos Equis and talking the night away.

I’ve gone on this long and I haven’t told you a thing about the art in the Land Arts show. That’s because the context is important. It’s also important to note that the works shown here are provisional, and, in some cases, placeholders for further inquiry and thought. Taylor says as much, when he’s quoted in this recent article, “In the end, this is about people’s trajectory on a much longer timeline.”

Some of the work here is forgettable. Some is a bit breathless with reverence for the land and the sun and the air and the highway. What will be interesting is to see these artists’ works further down the line, and how their experience in the Land Arts program affects their practice in the long run. (The smart work of Land Arts alum J Eric Simpson, whom I recently profiled on Glasstire, is a good example of this.)

But you can see some of the seeds already sprouting with promising and thought-provoking work. Shay Myerson’s sculpture of yellow dyed flour pressed into undulating hills and valleys by foam packing material is one such work. It’s like the dry chalk dust of the desert collected on the bottom of a hiking boot, in the form of a Wolfgang Laib pollen sculpture. Myerson has a video installation too, which gives a window onto some desert daydreams of water and telepathic communication, and a set of two suspended blue plexiglass ovals catching and reflecting light. Myerson is a recent graduate of Lewis & Clark College in Oregon, and I hope to see more of her explorations of color, material, and light in the future.

Cara Rae Joven, an MFA candidate at the University of California, Riverside, is another standout of the exhibition. Three video monitors hanging from the ceiling show Joven performing various physical feats in the landscape using climbing ropes, harnesses, and weights. In one video, she hammers a stake into the ground with a rope attached to it, links her foot into a loop in the rope, and, holding the other end and looking into the sky, attempts to lower her body as close as possible to the ground — seeking, but not achieving, a fully parallel posture to the earth. The setting sun casts long shadows and traffic thunders behind her from a nearby highway. In another, Joven suspends herself over a creek with climbing gear, lowering herself over the running water. She drags a sand bag behind her over a salt flat. In a different video, she situates herself in a small depression and swings the sand bag around her body by a long rope. Watching these in the gallery, riveted, I found my body gently swaying in sympathetic motion. Joven includes a written treatise on tools, evidence of a sharp intellectual basis to her performances, but the videos remain open-ended and malleable. They could fit any number of curatorial premises. It’s very strong work.

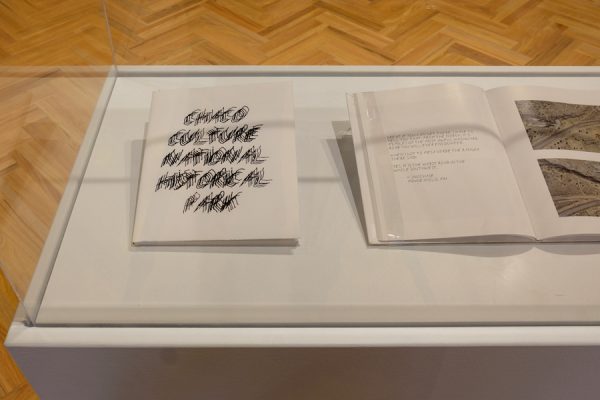

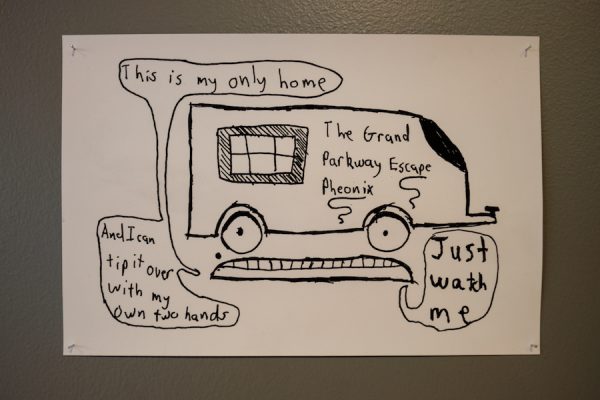

There are a variety of illustrations in the show, as well as poems and books, the best of which is a little booklet about Chaco Canyon by Elise Dupré, an illustrator and art historian who traveled from Belgium for the program. The book’s title is written in a striking, shaky script that gives a great sense of the “13 miles of the most awful washboard road you will ever encounter” leading to the site. Elijah Olson, a geography major at the University of Texas at Austin, provides some charming, lighthearted illustrations throughout the show — a glimpse into inside jokes and lecture notes he gleaned from the program.

One of the most valuable takeaways from the exhibition, as well as the long table dinner, is that little window into the experiential learning that happens in the Land Arts program. We are extremely fortunate that this program is based here in Lubbock. Geographically, it situates us as a springboard for exploration of the vast American Southwest. Intellectually, it connects us to a network of scholars and artists dealing with land use and land art. It feels a little like an outlier at the University here, though, and the program deserves more financial support and visibility. But perhaps because it is an outlier, the program retains its independent spirit — ranging out there in the field and on the road, stopping just long enough to show us some of the artworks it has inspired along the way.

Through April 21, 2019 at the Museum of Texas Tech University, Lubbock

1 comment

Fantastic! I’m going to have to go see Leonardo’s Kitchen in person now.