Dirk Braeckman’s Focus exhibition at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth may confound viewers’ expectations of photography. Rather than using the camera as a simple mimetic device, Braeckman explores the creative potential of the darkroom process. Set against white gallery walls, each photograph, with its deep gray tonality, appears like an opening into a void. Navigating Braeckman’s crepuscular world is a challenge; as you examine each image, it’s as if you have entered a dark room and your eyes need time to adjust until you can identify objects in the gloom.

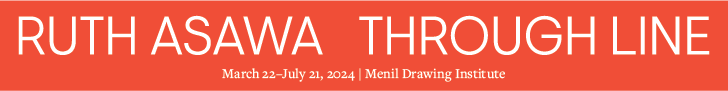

It may take an extra beat before you realize that one of the photos shows us a foot, which leads your eye to the body of a nude female figure lying on a bed. Throughout the history of art, most nude portraits depict something like a tangible, exposed body, but Braeckman’s dimly-perceived figure is veiled by darkness, and we can only manage to make out the outline of an insubstantial form or ghostly presence. It’s positively eerie.

Braeckman, a Belgian photographer who represented his country at the 2017 Venice Biennale and has exhibited his work across Europe, began his study of art as a painter at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent. When he was urged to try photography, he approached the medium with an experimental spirit. Like the nearly invisible nude, the signature style he developed pushes the photographic medium. The Modern’s associate curator, Alison Hearst, first spotted the artist’s work at the Biennale, and after learning that he had not yet had a museum show in the U.S., she decided he would fit one of the purposes of the Modern’s FOCUS exhibitions, which is to introduce visitors to artists gaining worldwide acclaim. Hearst says that the inclusion of several images of reflective water surfaces is a nod to the museum’s association with water in its reflecting pool.

Rather than creating reproducible images in an editioned series, Braeckman makes his photographic prints unique through his physical manipulation of the film negative and light during the development process. He might throw dust on the negative or into the processing chemicals during printing, or he may, during print development, control the light in a painterly manner via experimentation. During my interview with him, he said: “I don’t like to control everything — I need accidents, imperfections.” He says his negatives are difficult to print because they’re underexposed, and adds, “I like to break all the rules.” To cite an example, he pointed to his use of a flash during the exposure of his work B.J.-D.U.-12, with the gleam of the flash revealing the maker’s presence in the photograph. The dust specks scattered across several images may unsettle those conditioned to pristine photographs, but the added white noise serves to emphasize the surface layer of the flat photograph, and subverts the illusion of spacial depth, effectively creating a disruptive barrier.

Braeckman manipulates space through abstraction, as our depth perception is impacted by the limited light in the works. In one print, faintly highlighted architectural moldings that define a baseboard are repeated in an interrupted pattern elsewhere in the image. In another print, what seem to be geometric patches of light appear randomly skewed on a floor without a hint as to their origin.

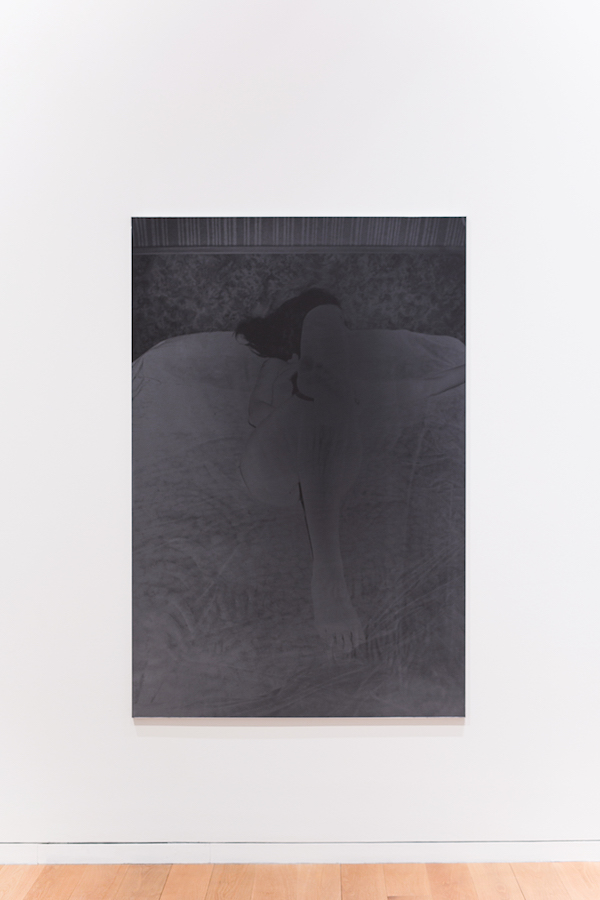

Another example of Braeckman’s rule-breaking is his photo with a pronounced glare on the surface that obscures a tangle of nude bodies. He rephotographed a photographic print that had creases and other imperfections on the surface texture of the paper, and he intentionally recorded the surface glare. Perceiving the bodies through the barrier of the glare exacerbates the mystery. Braeckman says that for him, the glare hiding the figures is more interesting than a plain image with no reflection — the print has several visual layers that he’s playing with. This is a show one needs to view in person, as published reproductions fail to convey the subtleties of the imagery and the lush matte surfaces of the prints. And Braeckman insists that his photos are displayed unglazed. So look, but don’t touch.

The subjects and locations of Braeckman’s photographs are anonymous. His cryptic titles are composed of letters and numbers identifying the year the print was made. As he travels, he photograph places (interiors and landscapes) that he later imbues with the drama of his tenebrist lighting. Braeckman agrees with Garry Winogrand’s oft-quoted remark: “For me the true business of photography is to capture a bit of reality (whatever that is) on film… if, later, the reality means something to someone else, so much the better.” Braeckman has previously said, “I’m not a storyteller. I’m an imagemaker. The story is made in the mind of the viewer.”

One room of Braeckman’s Focus show contains his landscape images. A mountain range is etched in Stygian darkness, as if a cataclysmic volcanic event plunged the world into deep gloom. Across the room, a triptych of monochromatic water images depicts a wave frozen in motion just as it crests. All of the wave images are made from the same negative, but each print is unique with special effects and tonalities. The glint of the camera’s flash on a wave indicates the fraction of the moment in which the image was captured; then the photographer stretched out that moment as he manipulated light during the printing process. Braeckman’s approach in the darkroom goes back to the experimental roots of photography. After he gets his negatives, he deploys light to effectively ‘paint’ powerfully resonant scenes in grisaille.

Braeckman offers us something that’s suggestive of knowable places and things, yet elusive enough to frustrate our attempts to interpret what we think we ‘see.’ Braeckman exploits the limitations of our visual perception as he pushes us to look closely when trying to make sense of the scene before us. With dimmed sight, we grope our way into a shuttered but strangely familiar world.

Through April 14 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth