At Texas State University’s Wittliff Collections in San Marcos, a variety of historical research materials illumine writers’ methods and explore the mysterious places where stories originate.

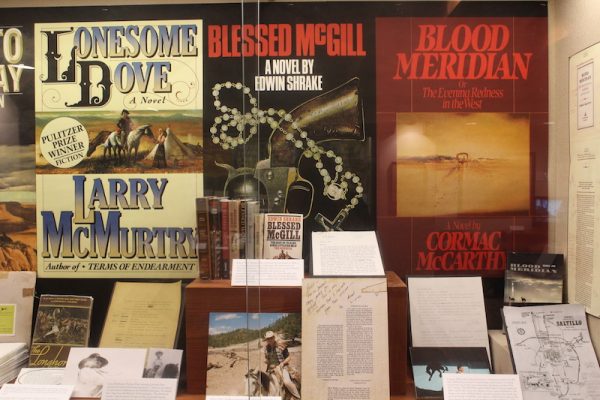

“It’s the cows. The cows are the problem.” Thus spoke CBS TV executives to screenwriter/novelist/photographer Bill Wittliff and the producer with whom he worked on the 1989 mini-series based on Larry McMurtry’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Lonesome Dove. The large number of bovine performers called for in Wittliff’s script adaptation would, the executives fretted, be way too expensive. Wittliff explained that the herd was necessary because the story was about a 19th-century cattle drive and then, exasperated, suggested the network save money by using goats instead of steers. “Great!” chirped an earnest exec. “We’ll make it a goat drive!”

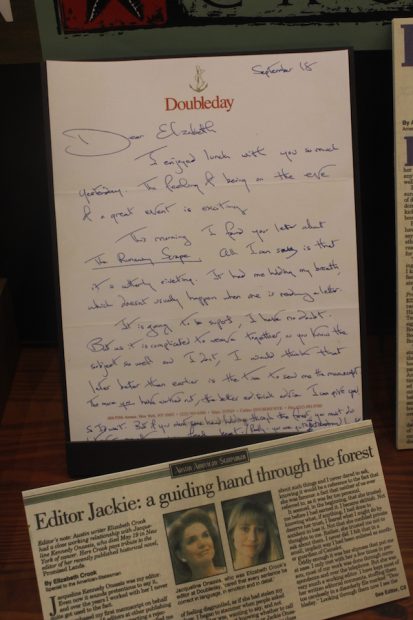

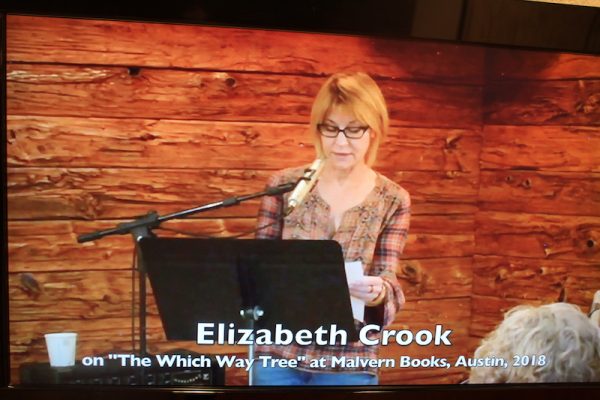

That true story and others play on a video loop in the exhibition Literary Frontiers: Historical Fiction & the Creative Imagination at Texas State University’s Wittliff Collections in San Marcos. In one clip, Sarah Bird, a white author, asks her African-American editor if she had reservations about Bird telling the story of Cathy Williams, who passed as male in the 1860s to join the black troops called the Buffalo Soldiers, in her novel Daughter of a Daughter of a Queen. Bird’s relief is palpable when the editor replies that the quality of her writing dispelled any such concern. Gallery visitors can also hear a ghostly voicemail message left for novelist Elizabeth Crook by the late First Lady of Camelot, who served as the editor for Crook’s 1991 novel, The Raven’s Bride, about Sam Houston’s short first marriage. “Elizabeth, this is Jackie,” says the breathy, elegant voice before praising the first chapters Crook had submitted.

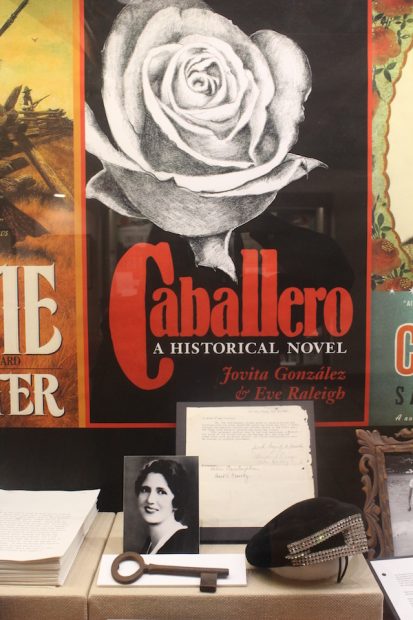

A paper letter from Kennedy-Onassis to Crook is among the exhibition’s authorial relics that include book covers, photographs, manuscripts, and even the key to folklorist and novelist Jovita González ’ family ranch. Displayed beside the enlarged cover of her novel Caballero, the key is accompanied by a photograph of González and one of her hats that appears to date from the 1930s or ‘40s. Written during those decades in a collaboration with Margaret Eimer, Caballero, signage informs, “is a historical romance that chronicles border culture during the aftermath of the U.S.-Mexico War of 1846-48. Caballero was rejected by publishers at the time and the manuscript was lost for decades.” Rediscovered and published in 1996, thirteen years after González’ death, the novel “has now become a milestone in Mexican American literature.”

The anguish of the aspiring author is further encapsulated in an example of the bane that has plagued even our greatest writers: the rejection letter. This particular dream-pooping missive was addressed to novelist David Marion Wilkinson, who collected some 300 such bummers before publishing his first critical and commercial success, Not Between Brothers: An Epic Novel of Texas, set in the era when our sprawling sod was a Spanish and then a Mexican province, and then an independent republic. Wilkinson wall-papered his office and a vacant next-door house with the rejection letters.

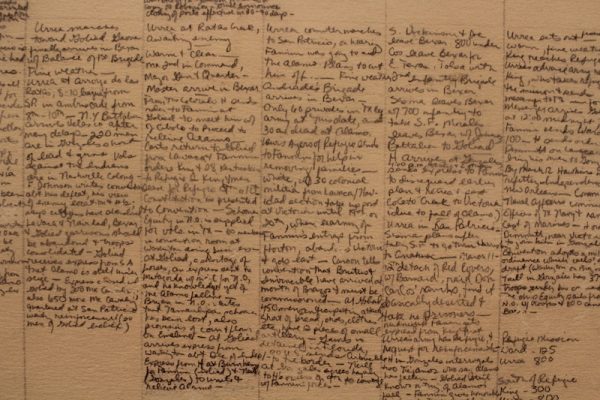

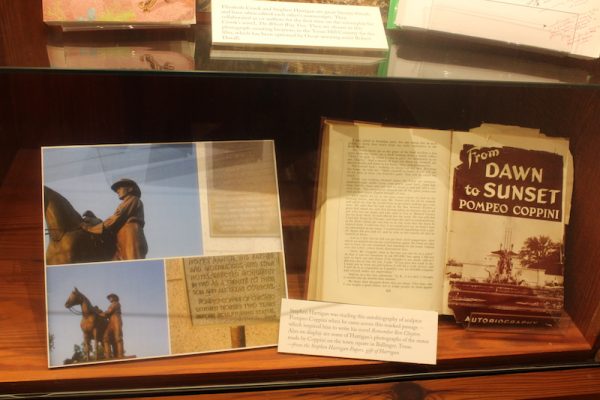

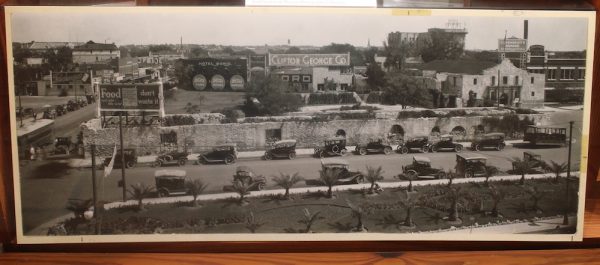

Imagining the past is one thing, but constructing a believable re-creation is quite another. A variety of historical research materials illumine the storytellers’ methods and explore the mysterious places where stories originate. Elizabeth Crook’s large poster of research data for Promised Lands: A Novel of the Texas Rebellion is filled with tiny handwriting charting the revolution’s timeline. A boyhood photo of Stephen Harrigan in front of San Antonio’s famous mission-turned-fort hints at the seeds of his novel The Gates of the Alamo. Nearby sits a vintage horseshoe from the Alamo grounds gifted to Harrigan by rock star and Alamo collector Phil Collins. And a folk-arty self-portrait of the self-described “Alamohead” author, created for a fundraiser, depicts Harrigan as a rifle-wielding Davy Crockett as a space shuttle rocket blasts off in the background.

A sculpture in the drawing of a cowboy standing beside his horse represents the Charles H. Noyes Memorial in Ballinger, sculpted by Pompeo Coppini in 1918-19. The statue, a tribute to Noyes and “all Texas cowboys,” was commissioned by his father after Noyes died in a 1917 accident on horseback. When Harrigan came across the story in Coppini’s autobiography, it sparked the novel Remember Ben Clayton, about a Texas rancher who engages a Coppini-esque San Antonio sculptor to commemorate his son lost on the battlefields of France in World War I.

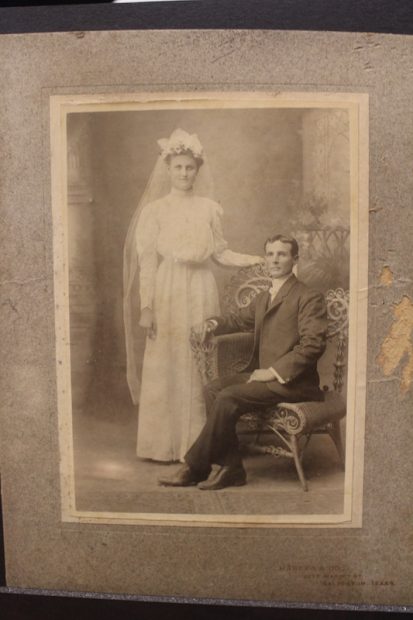

In 2008 Galveston writer Ann Weisgarber was working on The Promise, her novel about the massive 1900 hurricane, when Hurricane Ike hit the island. After the storm she found an anonymous antique wedding photograph in her yard. Included in Literary Frontiers, the image provided Weisgarber with inspiration for two of her characters.

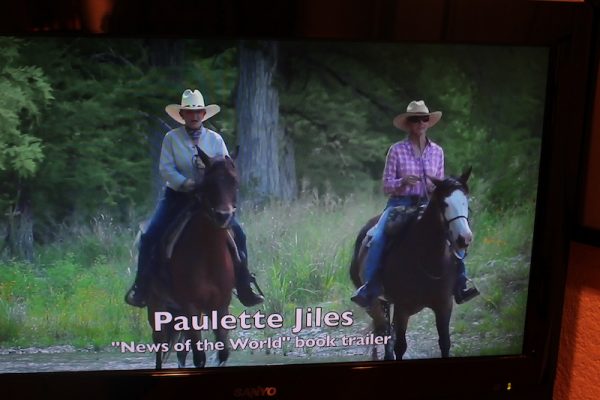

On the video loop, excerpts from the trailer for Utopia novelist Paulette Jiles’ latest book, News of the World, show the author riding her horse through the Hill Country. A finalist for the National Book Award, the 2016 novel joins the mildly crowded recovered-Indian-captive genre, which includes Jiles’ The Color of Lightning. (Harrigan’s Remember Ben Clayton deploys echoes of a captive tale.) It’s understandable why writers are drawn to the stories of captives so completely absorbed into an alien culture that they forget their original language, way of life, and even their former loved ones. In Jiles’ latest, a 70-year-old veteran named Capt. Jefferson Kidd, who makes a living traveling from town to town reading the news from a stack of regional and distant newspapers, is recruited to return a recovered young girl to her family near San Antonio. Kidd, based on the great-great-grandfather of a friend’s husband who actually traveled through frontier Texas reading the news, is set to be played onscreen by Tom Hanks. Robert Duvall has optioned Elizabeth Crook’s latest novel, The Which Way Tree, a Civil War-era story about a boy and his half-sister tracking the panther that killed the girl’s mother in the Hill Country near Bandera.

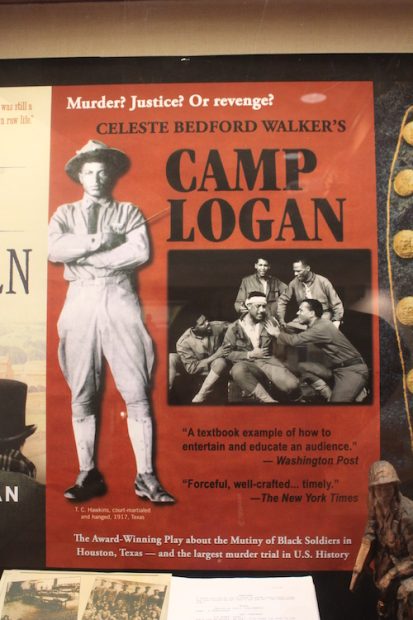

Script pages, posters, photographs, and newspaper articles document Camp Logan by Houston playwright Celeste Bedford Walker. The play addresses the mutiny of African-American soldiers at Houston’s Camp Logan in 1917, who rebelled against inhumane treatment by area whites and police. Four soldiers and sixteen civilians died, and nineteen soldiers were later executed for the rebellion. “If you’re curious about military history, if you want to see another side of patriotism, or if you’re just interested in basic human rights,” wrote one critic, “you will find this play profoundly interesting, moving, and most importantly, educational. I walked out of the theatre changed.”

Sometimes it can take a while for our own lives to catch up with a book. It took me 25 years to make it through Cormac McCarthy’s dense and brilliant Blood Meridian, which draws on historical accounts of marauding scalp hunters paid by the Mexican government to rid the republic of Apaches and other tribes. The current exhibition at the Wittliff, which hosted two previous major exhibitions based on its McCarthy holdings, includes the novelist’s annotated map of Saltillo, Coahuila and a Blood Meridian-era photograph of McCarthy taken in El Paso.

Photographs of a young Jan Reid, whose novel Comanche Sundown brings Quanah Parker vividly to life, and a young Larry McMurtry, both on horseback, indicate where the authors learned to describe riding hell-and-heck-for-leather in their books. A member of the “Mad Dog” school of Texas “literary outlaws,” Edwin “Bud” Shrake appears in a photograph taken on horseback in the Sierra Madre of the Mexican state of Chihuahua in 1966 while researching his masterpiece, Blessed McGill. Employed as a Fort Worth sportswriter at the time, Shrake wrote much of the novel by rising extra early and working on it a couple of hours each day before heading to the newspaper offices. If you’re ever in the Texas State Cemetery in Austin, check out Bud’s tombstone, next to the grave of his latter-life flame, Governor Ann Richards. Inscribed on Bud’s stone, a mere four words convey the suggestion of adventure beyond: So Far, So Bueno.

Literary Frontiers: Historical Fiction & the Creative Imagination is on view indefinitely (possibly ending this summer) at Texas State University Wittliff Collections in San Marcos. Other authors represented in the exhibition include Judy Alter, Robert Flynn, Elmer Kelton, Mark Busby, Joe Lansdale, and Sandra Cisneros. The video of a discussion held at the Wittliff with Elizabeth Crook, Stephen Harrigan, and Ann Weisgarber, moderated by Stephen L. Davis, may be viewed here.