Texas’ earliest extant photographic image, unsurprisingly, was made in San Antonio. The 1849 daguerreotype of the Alamo, archived today at the Briscoe Center for American History at UT Austin, shows the mission-turned-fortress before the U.S. Army added the familiar arched gable. Through the rest of the 19th century, San Antonio was the most photographed city in the state. Two current exhibitions in San Antonio — Destino San Antonio at the Briscoe Western Art Museum, and La Puerta: A Photographic Journey of San Antonio at UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures — provide rich and ample justification for that distinction.

Throughout the second half of the 1800s, Americans read tantalizing accounts of San Antonio’s cultural and physical landscape: “We have no city, except, perhaps, New Orleans, that can vie, in point of the picturesque interest that attaches to odd and antiquated foreignness, with San Antonio,” wrote Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of New York’s Central Park, in his 1857 Texas travelogue. “Its jumble of races, costumes, languages and buildings… combine with the heroic touches in its history to enliven and satisfy your traveler’s curiosity.”

Many of those curious travelers (whose numbers multiplied after railroad lines at last connected San Antonio with the rest of the country in 1877) wanted souvenir images of that picturesque jumble, as did armchair tourists imagining this distant, exotic place. Historians have identified about 100 photographers who worked commercially in San Antonio before 1900. Destino San Antonio exhibits cabinet card and stereograph images that were sold all over the city and beyond. “It was a challenge,” Briscoe Vice President Liz Jackson told me, “to find a way to present these small-format images that would broaden the experience for museum visitors.”

To my eye, the Briscoe has succeeded beautifully in that effort. The museum commissioned San Antonio artist Anne Wallace to curate the exhibition, and Destino reflects her practice of engaging the American West to examine “issues of representation, authenticity and myth.” She selected the dozens of stereograph images on view from a collection of 600 Alamo City stereograph photos that the Briscoe acquired in 2014 from Houston collector Robin Stanford. They explore Olmsted’s “jumble” of life and landscape through a lens that reveals how the city was portrayed in the 19th century and how its history is manifested and perceived today. And while some of the images on view are widely reproduced in books, seeing the actual stereoview and cabinet card photographs is a primary visual experience at least somewhat akin to encountering any work of art when one is familiar with its reproductions.

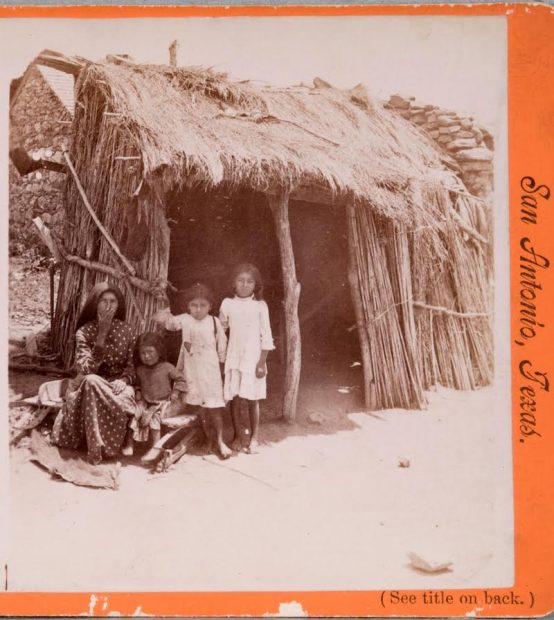

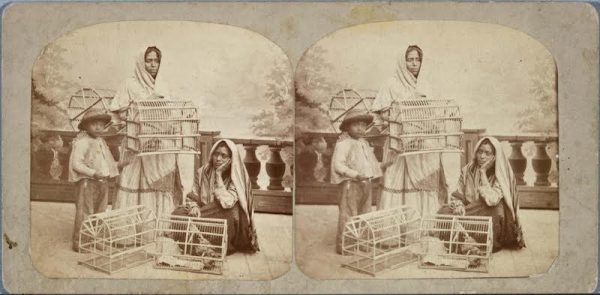

San Antonio photographer Frank Hardesty advertised the “Largest Collection of Fine Stereoscopic Views in Texas” and “Views Made to Order Anywhere.” His image Mexican Jacal Family depicts a common home construction method utilizing branches, mud daubing, and thatched brush. According to wall text, five 19th-century jacales remain in Bexar County. The weary expressions of the ladies in Pagarias (Mexican Women Selling Birds) by Doerr and Jacobson indicate the challenges of capturing and selling to tourists mockingbirds, canaries, and cardinals. “Mexican women monopolize the bird selling trade and are adept at it,” wrote Stephen Gould in The Alamo City Guide, published in New York in 1882. They “are as a rule better traders than the men.” Henry A. Doerr and Samuel E. Jacobson, who had a brief business partnership, appear often in 19th-century San Antonio photo credits. Destino images such as The Aqueduct at Mission San Juan by M. E. Jacobson were made by Mary E. Jacobson.* It was not uncommon, of course, for women to use first and middle initials when working in fields that were dominated by men.

Wall text affirms that 19th-century San Antonio was residentially segregated but also notes that vintage images reveal significant cultural mixing in public plazas and at San Pedro Springs, the second oldest park in the United States. Hardesty’s image The Plaza “Dude” depicts an African-American dandy in a high-crowned fedora, vest, and cutaway coat standing beside a Military Plaza market table laden with fruits, peppers, and vegetables. A good selection of Destino images of the plaza, including Hardesty’s Military Plaza (pictured below), reveal why San Antonio chronicler Charles Ramsdell called it “the liveliest spot in Texas” in the closing decades of the 1800s. Multiple stereographs on view capture the plaza tables where tourists and locals dined al fresco on cuisine served by glamorous “chili queens” that, according to novelist Stephen Crane, tasted like “pounded fire-brick from Hades.”

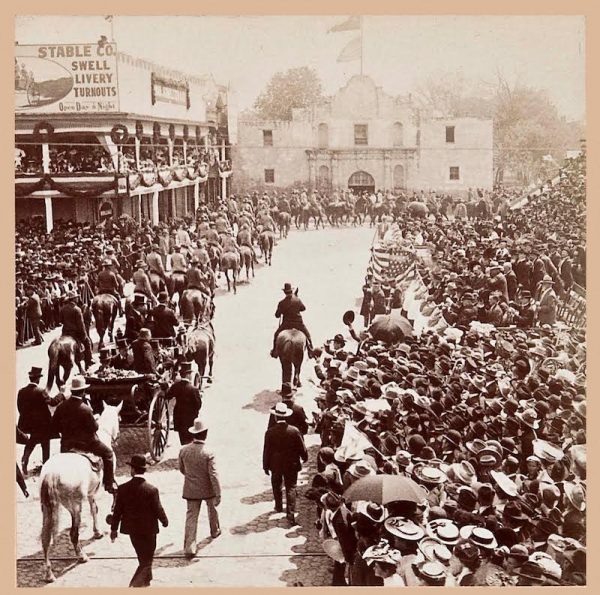

San Fernando Cathedral on Main Plaza is an impressive structure whether viewed in person or in images from any period. But there’s an added, majestic dimension to vintage images like Hardesty’s Destino photograph of the cathedral (pictured at top) that catches locals on the plaza shooting the breeze in mostly empty wagons, that day’s load of firewood or hay already sold on the adjoining Military Plaza. The same effect is operative for B. W. Kilburn’s 1905 image Pres. Roosevelt Arriving at the Alamo, though the atmosphere is not relaxed but charged as the packed crowd awaits Teddy’s speech.

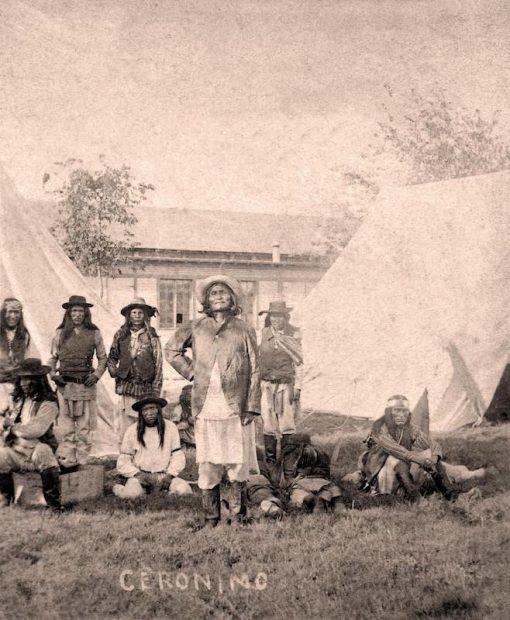

Curator Wallace includes in Destino San Antonio a double-lensed 1880s W. J. Chadwick Mahogany & Brass Stereoscopic Camera. Re-creations of stereoscope viewers hang throughout the exhibition, providing the complete, hands-on antique 3-D experience. Short videos by a variety of scholars and collectors further enhance Destino. Vintage image collector Lawrence T. Jones III, who placed much of his collection of Texas photographs at SMU after publishing Lens on the Texas Frontier, describes the stereograph craze as “the television of its time.” Kiowa-Apache tribal historian Jackie Dale Tointigh speaks of the belief held by some Native Americans that being photographed was equivalent to having one’s soul stolen or one’s spirit “caught.” He points to a widely-published image of Geronimo with other Apache POWs in San Antonio in which Cochise’s son looks away from the camera. Held at Fort Sam Houston for a time after their final surrender in 1886, Geronimo (one of the most photographed 19th- and early 20th-century figures in America) and the other Apaches were gawked at by crowds of San Antonio excursionists as though they were primitive dioramas in an anthropology exhibit.

In another deft curatorial move, a selection of 25 Destino images are projected in a wall-size slide show that moves through 19th-century San Antonio so hypnotically that one almost feels he or she can step into the picture and saunter through its landscape. And you needn’t have been long immersed, as I have, in a project about 1880s San Antonio and Military Plaza to feel a twinge of infatuation with this nifty scrim of visual time-travel. It’s cool.

Passengers board airliner at Stinson Municipal Airport, 1939. San Antonio Light Photograph Collection

While Wallace had hundreds of images to choose from, senior curator Tom Shelton at UTSA’s Special Collections at the Institute of Texan Cultures faced the daunting task of selecting 300 images from the collection’s 3.5 million images for La Puerta: A Photographic Journey of San Antonio. It helped, of course, that Shelton has been nurturing this amazing archive for decades. I can’t imagine cataloguing that many images, but over the last umpteen years whenever I have needed, say, a photograph of San Antonio magician Willard the Wizard mesmerizing a chicken, or Dr. Charles Campbell with his 1920s Alamo City bat roosts, I have consulted this collection.

Members of the San Antonio Volunteer Fire Department on a swan boat in San Pedro Park, July 4, 1891. San Antonio Light Photograph Collection

Girls model swimsuits to be worn at the bathing girl revue, a feature of the annual tourist day celebration, 1926. San Antonio Light Photograph Collection.

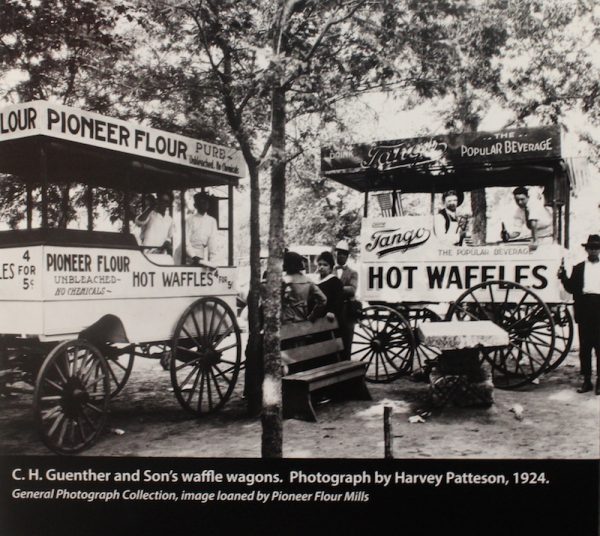

Organized by decade, Shelton’s selections include the expected marquee scenes of the river, the missions and plazas, San Fernando Cathedral, humble domains of the barrio Laredito, San Pedro Springs, and less-heralded but perhaps more mysterious spots such as the Veramendi Palace, Hot Sulphur Wells, the Japanese Tea Garden, and a music-and-dance performance at Miraflores, the garden estate of Dr. Aureliano Urrutia. Refugees from the Mexican Revolution line up for food at the Municipal Market House in the 1910s. A woman with bobbed hair reads the latest magazines at a downtown newsstand circa 1924. Photographed that same year, Pioneer Flour’s Hot Waffle wagons read like flapper-era food trucks. A 1929 Westinghouse robot displayed with appliances it can operate gives a funky taste of futurism.

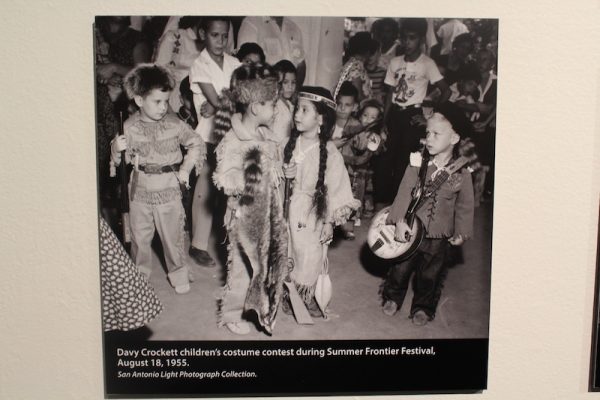

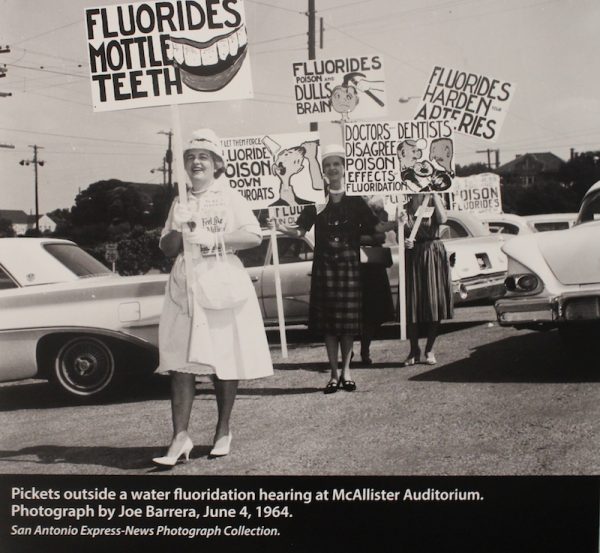

A 1955 image of children dressed for a Davy Crockett costume contest is either a soft piece of nostalgia, an unsettling caricature of cultural tone deafness, or something in between. Similarly, a photo of proper ladies in hats and gloves protesting water fluoridation in 1964 delivers a collision of signification and context. Protesting sex and violence on television, a group of intense and smiling hombres seems to have lost their minds as they wield bats and sledgehammers to whack the guts out of a pile of TV sets at a 1985 “smash in” event. As a panorama moving through the decades, the images present a rolling chronology of style and pastime that brings our collective memory into the glimmering yet gawky end of the previous century. Many are puro San Antonio, while others — backyard bomb shelters, teen-scene record hops — could be any glorious urban wasteland.

These are echoing images of distant lives that remain, almost magically, fresh and familiar. Places lost and lingering still. Shadows, whispers, fragments of time heaped upon time that hang in the atmosphere of San Antonio like no other metropolis in this immense land mass. The past is not dead, the old adage avows. It’s not even past.

**

‘Destino San Antonio’ is on view at the Briscoe Western Art Museum, San Antonio, through January 21, 2019. ‘La Puerta: A Photographic Journey of San Antonio,’ also presented under the title ‘San Antonio 1860s – 1990s’ is downstairs at the Institute of Texan Cultures in San Antonio through March 31, 2019.

*According to Catching Shadows – A Directory of 19th-Century Texas Photographers by David Haynes, M. E. Jacobson was Mrs. Mary E. Jacobson, and S. E. Jacobsen may also have worked under the names Samuel E. Jacobs and Semmy E. Jacobson.