This conversation took place over email this last week, which sees the release of the long-awaited book, Collision: The Contemporary Art Scene in Houston, 1972-1985, by Houston writer Pete Gershon. There is a book launch event this Sunday in Houston. See bottom for details.

Christina Rees: First of all, congratulations! Collision is a beautiful book. Every major American city should be so lucky as to have a self-driven art historian do a massive project like this. I want to ask about the time frame you chose to cover: 1972-1985. Why those years for Houston’s visual art scene?

Pete Gershon: Hi, Christina, and thank you so much for your kind words about the book!

Collision is bookended by two landmark exhibitions. The first of these is a show called 10, which was organized for the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston in March 1972 by its then-director, Sebastian “Lefty” Adler, to inaugurate the new corrugated metal building designed by the Michigan-based architect Gunnar Birkerts. The building itself made a bold statement about how contemporary art would be presented as Houston moved into the oil boom years, and Adler commissioned ten vanguard artists from around North America to come to Houston to design site-specific installation pieces. There was a trench with a wave machine in what’s now the Cullen Sculpture Garden; an indoor farm arranged under grow lights; and a light show programmed into the display screens of the Goodyear blimp.

Installation view of Ellen Van Fleet’s ‘New York City Animal Levels’, March 1972, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. MS690 Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University.

The most infamous piece, though, was by a California artist named Ellen Van Fleet. New York City Animal Levels consisted of a wall of tiered cages containing birds, cats, rats, and cockroaches. By all accounts it smelled terrible and some of the animals and roaches escaped into the crowd on opening night. Houstonians in 1972 didn’t recognize any of this as “art” and people who’d donated large amounts of money for the new building were really very upset. By the end of the year, Adler was gone. But I think this show was a real turning point for the Houston art scene, which had previously been somewhat provincial, despite the presence of many talented artists.

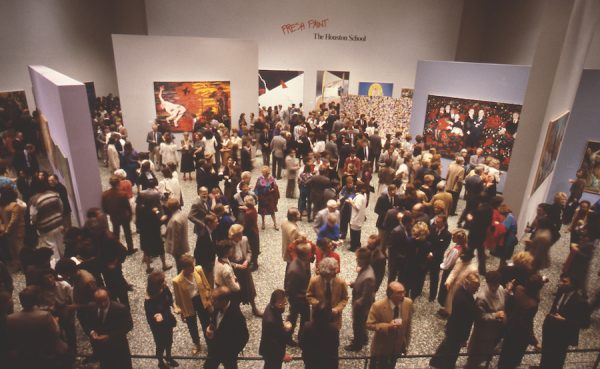

Opening reception for ‘Fresh Paint,’ January 1985, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo by Ben DeSoto

The second exhibition was called Fresh Paint: The Houston School, presented by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston in January 1985. Organized by the MFAH’s superstar curator Barbara Rose and Houston-based critic Susie Kalil, the show featured 56 works by 44 artists with ties to Houston. To this day, it was the museum’s biggest and boldest attempt to catalog home-grown art activity and it was something of a media sensation, with bumper stickers, live news broadcasts, and full-length articles in all of the glossy national art magazines. There was a sense that with this show, Houston would be considered to be a major art-producing city, on a level with Los Angeles and Chicago, but it never quite worked out that way. Part of it was the crashing economy. Another part was Rose’s resignation after a stormy few years at the museum. She alone had the clout to take the show to New York City, Los Angeles, and Europe. The show did make it to PS1 in New York, but the energy behind it kind of dissipated. Still, the show capped an era of intensive artistic growth, and the seeds had been sown for the rich and variegated art scene that we know today.

CR: Your book is a mind-boggling undertaking, and the best document of any history of Houston art to date. Besides the impact and influence on Houston of James Surls and Jim Harithas, and the relaunch CAMH in its new building and the launch of Lawndale, what other figures, institutions or events stand out to you as truly significant during these key years?

PG: There are so many! It is true that Harithas and Surls shaped the scene, but they weren’t alone. I am particularly impressed by the work of the members of the Houston chapter of the Women’s Caucus for Art. When Houston hosted the National Women’s Conference in 1977, the national WCA sent representatives to present panels and workshops. It might not come as a shock to hear that in the 1970s, it was very difficult for women artists to find opportunities to show work or engage in a meaningful dialog about art-making. The men could drink and flight at Chaucer’s bar in the basement of the Plaza Hotel; with just a few exceptions, women were left making art in isolation at their kitchen tables. After the conference, women like Lynn Randolph, Trudy Sween, Toby Topek, and Suzanne Bloom, along with dozens of others, organized collectively. Not only did they establish a peer group and an alternative art space to present work by both women and men, they also engaged in a series of boycotts and letter-writing campaigns that led a variety of well-established organizations to re-examine their priorities and improved the lot of all working artists in the city.

Members of the Houston chapter of the Women’s Caucus for Art at the Firehouse, 1413 Westheimer, in 1983. Photo © Debra Rueb.

I also have to mention Ann Harithas’ landmark exhibition, from which Collision borrows its name. Collision: Independent Visions opened at the Lawndale Annex in September 1984. It featured a range of artists working with a kind of bricolage technique, which was very inspiring to artists in Houston, many of whom were already working with castoff materials, the detritus of a city that was constantly tearing down its past. Included in the show were a pair of cars decorated by the California artist Larry Fuente. Jackie Harris had already made a couple of art cars by then, but this was undoubtedly one of the events that inspired Houston’s art car movement.

The research was really addictive, and I am so lucky to have had mostly unrestricted access to the archives of the MFAH, the CAMH, and Lawndale, along with the personal papers of many individual artists and administrators. I worked on this book slowly and patiently for about five years, and even with about 140,000 words, in some ways I feel like I have only scratched the surface of what was happening here.

CR: Is what you found in your research what you expected? What most surprised you about this history?

PG: Well, I am not sure I came into the project with any particular expectations. The genesis of this book was some work I did several years ago with artist Bert L. Long, Jr. as a participant in the CALL Project, a foundation-funded initiative to help artists document their work and organize their papers. Bert was a pack rat and saved absolutely everything, so helping to arrange his archive was an incredible opportunity to see the entire sweep of what was happening in Houston’s art community during these years. Bert talked a lot; it was just one story after another, and as a writer I could immediately tell that there was a great book waiting to be written. I had a pretty good sense of what I was getting into; it was really just a matter of drilling down into the details.

CR: I feel like a city’s ability to embrace conceptual and experimental art and art events is a marker of it willingness to embrace contemporary art (or at least I did until recently). What was Houston’s relationship like with conceptual art (both from its own artists and work from outside) during those years? How has that changed?

PG: I think it is safe to say that in the 1970s and into the 1980s, Houston was a painting and sculpture town. That said, conceptual art did indeed have a footprint in the city. In the mid-‘70s, Barbara Cusack ran a gallery out of a beautiful brick house a few blocks away from the CAMH; she hosted exhibitions there by the likes of Carl Andre, Lawrence Weiner, and Richard Tuttle before they were very well-known. Allan Kaprow came to Rice University in 1972 for a “happening” — he brought students down to Galveston, had them fill suitcases with sand and then mail them to themselves, only to drive them back to the beach to dump them out.

The infamous performance by the Kilgore Rangerettes at the CAMH’s opening for its Antoni Miralda show (and the ensuing brawl) can easily be read as conceptual art with uniquely Texan flair. So could Bert Long’s monumental ice sculptures. Artist-critic Douglas Davis staged a significant conceptual piece at the Astrodome in 1976, and Patricia Restrepo managed to track down some fascinating documentation of this for her incredible show that’s on view at the CAMH right now. Everyone should go see it!

Later on, of course, the Art Guys would meet each other as students at the Lawndale Annex in 1981. Their first piece, The Art Guys Agree on Painting, was pointedly a rejection of Houston’s seeming obsession with the medium of painting. Things have changed a lot since the era I’m studying, in Houston specifically and the wider art world generally, and it seems as though the boundaries have blurred. Is Project Row Houses a kind of conceptual art? Or Dario Robleto’s work? Or the work of recent Core fellows like Sondra Perry or Felipe Steinberg? I am not sure these artists necessarily think about their practice that way, but Houston is clearly much more comfortable with nontraditional, research-based artwork that combines media, performance, the archive, et cetera.

CR: In retrospect, what did you leave out that you wish was included (if anything)?

PG: Here’s a caveat about the book: it’s not an encyclopedia, but rather a narrative, with four specific story arcs. As a result of this, there are a number of wonderful and very important artists and administrators who admittedly don’t have much of a footprint in Collision. I’ve long since recognized that even in a long, detailed book, there’s no way to include everyone and everything. Now I’m thinking of the book as a just one component of a larger research project, one that comprises a series of exhibitions (such as the one up right now at Glassell); original online content; archival projects; and public programming. I am certainly not done writing about this subject, and I hope this book will be a starting point for future scholarship by others. It’s going to take a village to document a village.

CR: Will there be a next book, a “Collision 2”? And what advice would you give to historians, especially art historians?

PG: There very well could be. I do have a couple of related book project ideas that I am trying to sort through, though I think they would be very different from Collision in terms of format and approach. Stay tuned! And I have to admit I am not a typical art historian. Most have deep backgrounds in art theory, while I come at this as more of a journalist and aspiring archivist. I really hope that art writers will tackle similar projects in other cities. I’d be super interested to read about the histories of the art scenes of Kansas City, Cincinnati, Baltimore, wherever. I am sure there are amazing stories waiting to be told. Advice? Don’t wait. Do it right now. The clock is ticking and we’re all getting older.

CR: Is there a favorite story that you came across in your research that you’d like to share here with Glasstire readers (who we hope and assume will get their own copy of Collision in the coming days)?

PG: I mentioned before the Rangerettes and the bread-throwing incident at the CAMH, which is a great story and one that was excerpted from the book in Arts & Culture Texas — your readers can easily look it up and have a read.

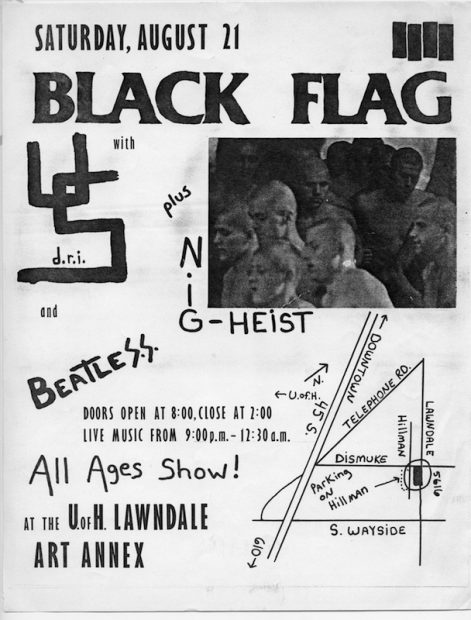

I’ll give you a different one, though, that Surls shared with me. It was 1982 and the Lawndale Annex hosted a performance by Black Flag, a hardcore punk rock group from LA that was notorious for their rowdy shows. For those who might not know, the original Lawndale was a ginormous, mostly unsupervised warehouse in the east end, into which the U of H art department had been moved after a fire on campus. By the end of the night, the police had broken up the concert and the place was trashed. Word made it back to members of the U of H administration, who came to Lawndale to chew out Surls.

When they arrived, they walked in on a Girl Scout troop pot-luck brunch, with proud families dressed up in their Sunday best. The flummoxed administrators asked if this kind of thing happened often at Lawndale. “Oh yes,” Surls assured them. “We try to be responsive to all parts of our community.” They left quietly, and Lawndale had dodged yet another bullet. James Surls is a world-class yarn-spinner, and while I couldn’t confirm all the details of everything he told me, this story is a personal favorite.

Note: This Sunday, Sept. 23, there is a book launch, panel talk and book signing with Collision author Pete Gershon at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. It starts at 1 pm, with the panel discussion at 2 pm; the book signing starts around 3:30 pm.

1 comment

Great times, great to see this coming full circle thanks to Pete and all those who contributed.