Cressandra Thibodeaux’s My Box Series, up now at G-Spot Gallery in Houston, poses some loaded questions regarding the objecthood of the female body and its potential use as a political statement. Where is the boundary between a woman’s subjectivity and objectification when depicted nude? How, in this political climate, can a woman use her body to command empathy? How can nudity ask larger questions regarding the governance (or lack thereof) a woman has over herself, especially considering the history of the female body’s subjugation in (art) history?

Although a singular body of work, My Box Series takes on three basic photographic trajectories: images of female models in loose, organic poses printed on brushed aluminum; images of models in similar poses printed on mirrors; and images of those same models lying on their backs, their vaginas facing the camera, posed as if they are waiting for an inspection from a gynecologist. (A pose that can’t help but echo Courbet’s L’Origine du monde.) And while these trajectories may provide some range and dynamism to the show, the pieces engage with the current political discourse about women’s bodies with varying degrees of success.

Cressandra Thibodeaux, Woman 9, 45 x 30, printed on mirror

By and large, the more literal Thibodeaux gets with her work, the worse. This is most evident with the grouping of prints on mirror, the majority of which have a large red arrow overlaid with bold white print reading “Your views here” pointing near or directly at the model’s ass, which is blocked out by a stripe of mirror. While humorous, this image dilutes the political discourse into the kind of “us versus them” mentality that not only gets us nowhere, but also simplifies a deeply complex issue. The stripes work better as non-representational tools, exacting incisive abstractionist violence against the models’ bodies, viciously truncating these otherwise intimate portraits.

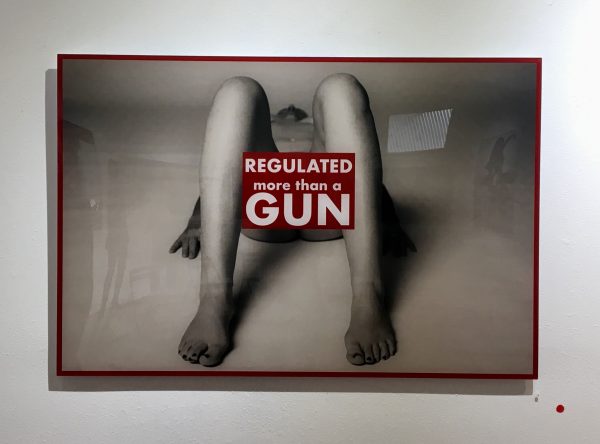

The Barbara Kruger Jr. tactics of Ben-Day dots and imposing white text atop a flashy red background further dilutes the conversation because, by employing a visual language that already has so much baggage, Thibodeaux is pointing to an overwrought postmodernist sensibility of removal and appropriation that dictates irony and detachment. There is simply too much of an urgency for realness in our world that we don’t have time for detachment; there are too many women who are genuinely afraid in this moment.

Cressandra Thibodeaux, Woman 3, 45 x 30, printed on plexiglass

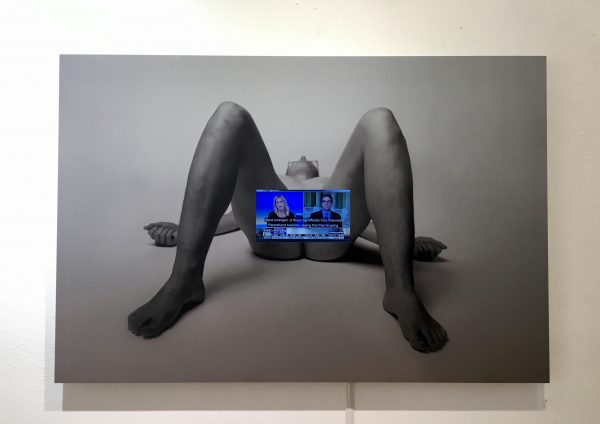

Thibodeaux instead garners our empathy with the tactility and vulnerability that comes with the technique of highly detailed portraits printed on aluminum. This is why the grouping of women positioned on their backs constitutes the best trajectory in the show: when Thibodeaux intimately pores over every hair, dimple, curve, or wrinkle of her subjects, she lends a voice to their autonomy, a pertinent and important reclamation. The technique behind the works also serves as a startling counterpoint to the clinical, almost morose way these women are laying. The silvery tones of the aluminum simultaneously render their skin sumptuous and drained of life — a jarring juxtaposition that leaves us wondering if they are preparing for sex or are being repositioned at the morgue.

What’s additionally chilling are the monitors covering the women’s vaginas, which are blaring videos of smarmy politicians squawking half-baked rhetoric about reproductive rights. Like some kind of invasive, nauseating political cunnilingus, it’s a painful reminder of how the discourse surrounding women and their own bodies is so often dominated by men who obviously have no idea what the hell they are talking about.

The best work in this show, however, is Thibodeaux’s artist statement, which reads as follows:

“…Recently, a journalist asked me about my abortion story—well here it is:

Getting pregnant was harder than I had ever envisioned. And in 2009, I tried “In Vitro Fertilization,” an assisted reproductive technology commonly referred to as IVF. On my 5th round of IVF, I finally got pregnant. However, my doctor explained it was an ectopic pregnancy, meaning the fertilized egg was in my fallopian tubes. She said that she’d have to administer a shot that would kill the cells.

I quietly responded, “Let me pray on this.”

She said, “What?”

I said, “What?”

“You said you’d pray on this?”

“I know. That was weird,” I admitted.

“Cressandra, do you NOT believe in science?”

“Of course I do,” I said, “I’m here aren’t I?”

Frustrated, she raised her voice, “If you allow these cells to grow in your fallopian tube, it will rupture and you could die. You need a shot of methotrexate—“

“I said I want to pray on this!” And I left the office.

And so began my journey—I would pray in the morning that my ectopic pregnancy would move to my uterus (which is impossible) and at night I would pray for the strength to get the methotrexate injection. I wished I could have shared this with my husband, an atheist, however, I was ashamed of my religious views because they were putting my life at risk.

Around Dec. 21st, my doctor called me to her office to inform me they would be closing for the holidays and would not reopen until January. ‘I am now giving you this package of injections that you must administer yourself. You have placed your life at risk and honestly you’ve disappointed me as my patient.’”

“Sorry,” I said and took the methotrexate injections home in a to-go bag.

Finally, on Christmas Eve, I went to the bathroom and prepared the injection. I looked in the mirror and as I pressed the needle into my belly I felt I was going through an internal battle to take back my body. It was the lowest point in my life and one of the greatest gifts I’ve given myself…”

Cressandra Thibodeaux, Woman 4, 45 x 30, printed on brushed aluminum

In short, Thibodeaux’s My Box Series continues a very timely, very important conversation about reproductive rights, but simply cannot on its own encapsulate the intimacy, claustrophobia, shame, and relief that comes with the ability and the responsibility of a woman to make extremely difficult decisions about her own body. This series of artwork also can’t solely communicate how the discourse around that choice so often becomes drowned out by methods of control, shame, and pressure not only from the government, but from even the most well-meaning and beloved people in our lives.

This work is necessary, but it does not do itself justice as a solo show. There is an urgency for a show in Houston that centers around the bare honesty present in Thibodeaux’s artist statement — that delves into women’s reproductive rights in a way that is comprehensive, authentic, multivalent — that reaches beyond the same self-congratulatory liberal clap-trap that shows up over and over and over again in the arts community. When these shows crop up, they do little more than reinforce the thoughts we were already thinking. If someone were to put together a show around an artist statement like Thibodeaux’s, it could change the game entirely. So, who’s going to organize it?

My Box Series is on view at G-Spot Gallery in Houston through August 26, 2018. The gallery will host a closing reception for the show on August 25th, from 6-8PM.