In Orhan Pamuk’s great Turkish novel from 1998, My Name is Red, a mystery about miniaturist painters at the height of the Ottoman Empire, one passage reads:

“The beauty and mystery of this world only emerges through affection, attention, interest and compassion; if you want to live in the paradise where happy mares and stallion live, open your eyes wide and actually see this world by attending to its colors, details and irony.”

I thought of this book while viewing James Smolleck’s beguiling, imaginative show at the Southwest School of Art in San Antonio. I also thought of the films of Alexander Jodorowsky, the incredible collection of paintings found in a chest of the Maharaja of Jodhpur, and the music of Popol Vuh. Basically my favorite things. It’s always a thrill to see an artist, whose interests seem similar to yours, articulate a synthesized vision. Smolleck’s detailed, ornate paintings and collages occupy the space between Stravinsky’s dream that inspired The Rite of Spring of a girl dancing by a fire surrounded by barbarians, and the beginning scene of The Exorcist, when Max Von Sydow finds a twisted little stone homie in an architectural dig in Iraq and immediately knows that it marks the return of a demon from hell. Something foreboding and monumental, charged with the power of the mind and memory to see a hooded figure in a tower and create a whole strange kingdom out of the vision.

Smolleck’s works are simultaneously highly detailed and breezy with its references and aesthetics. The gallery statement reads: “Borrowing elements from classical mythology, numerology, occult science (theosophy) and sacred geometry, James Smolleck’s collage work, drawings and paintings are potent yet whimsical parables that unravel the traditionally hermetic practice of self-discovery. His hybridized subjects — at once humanoid and animistic — roam vast landscapes, occupy sacred interiors and partake in esoteric rituals upon backdrops influenced by everything from the Flemish Masters and Medieval architecture, to theatrical backdrops and science fiction.”

Smolleck puts symmetry to good use throughout his works. One sequence of large drawings buttresses a scene of jesters in ritual around a chessboard, with the two end pieces depicting towers guarded by hooded and masked sentries. Another mirrored diptych collage depicts a hairy figure — a devil, a faun, some trickster — entering and exiting a triangle portal to the cosmos. Loops and cycles resonate throughout the show, repeating the same dream, the same reign, the same spirals of the library of Babel. The aesthetics may vary, but the world and its history make up an endless palace whose rooms fold back onto themselves.

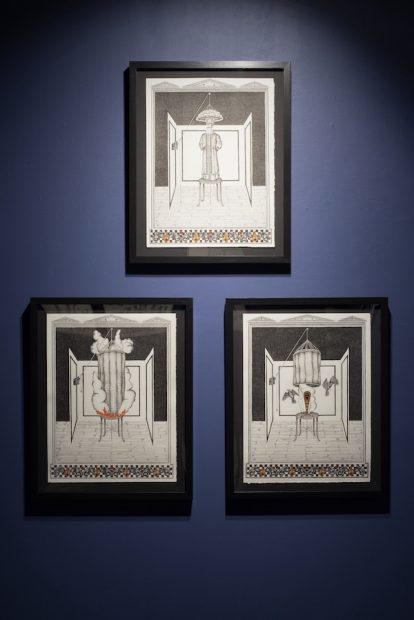

My favorite sequence is three drawings in which a robed man on a pedestal is, by the act of a disembodied hand, covered in a tubed tent, set on fire and revealed to be transformed into a glittering totem and pair of fluttering birds. It cleverly summarizes the dream logic of alchemy and resurrection. Like the hilariously intricate scene in Jodorowsky’s film The Holy Mountain, where a shaman turns shit to gold, this sequence revels in the endearing absurdity of magic and faith.

Smolleck’s wry humor throughout elevates the works. The subject matter and precision of the pieces could easily veer into “art-doom metal album cover.” But Smolleck has an incisive and warm eye. He sees both the splendor and the silliness of regalia, religion, ritual — and the reality of death and the illusion of time. These works link together like the chain of darkened, moving figures on the horizon at the end of Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. When the traveling jester Joseph spots them, he remarks: “And the strict master Death bids them dance. He wants them to hold hands and to tread the dance in a long line. At the head goes the strict master with the scythe and hourglass. But the Fool brings up the rear with his lute. They move away from the dawn in a solemn dance, away towards the dark lands while the rain cleanses their cheeks of the salt from their bitter tears.”

At the Southwest School of Art, San Antonio, through July 29, 2018.

1 comment

What an insightful article.Thank you Neil Fauerso.